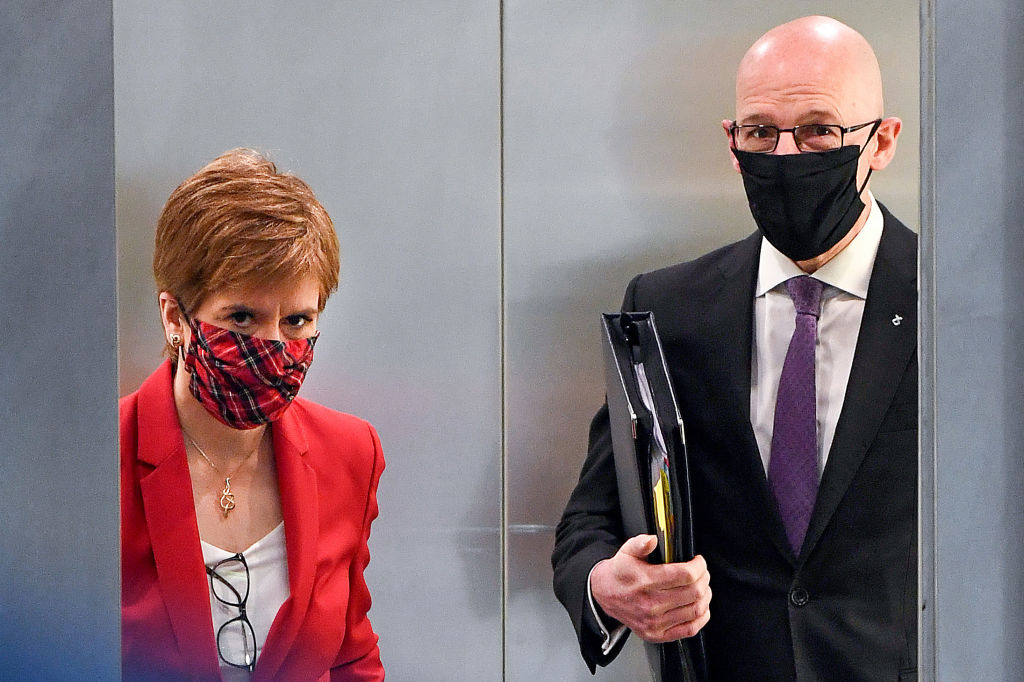

Whenever the Scottish nationalists start talking about ‘fairness’, you know someone’s getting shafted. SNP education minister John Swinney has cancelled Scotland’s higher exams for 2021. Not out of concern over safely administering the assessments in a socially-distanced manner, but because letting them go ahead at all could be ‘unfair’. Nicola Sturgeon’s deputy told the Edinburgh parliament on Tuesday:

‘Exams cannot account for differential loss of learning and could lead to unfair results for our poorest pupils. This could lead to pupils’ futures being blighted through no fault of their own. That is simply not fair.’

You might remember Swinney from his previous stance on exam fairness. That was back in the summer, when he presided over the downgrading of 125,000 exam results from the 2019/20 academic year. Pupils from the most deprived backgrounds were twice as likely to be marked down from their teachers’ predicted grades than youngsters from well-off areas. After five days of trying to hold the line, the SNP, up for re-election next May and facing a backlash, relented and upgraded all 125,000 results.

Swinney hasn’t had a good year at all. Even before the downgrading row, he had incurred the wrath of parents with his plan for ‘blended learning’ — i.e. part-time schools — another policy (nominally) dropped after public outcry.

Any notion that Swinney’s decision is motivated by fairness, as opposed to a desire not to jeopardise his party’s healthy polling lead, is easily debunked by paying attention to the analysis of Lindsay Paterson, professor of education policy at Edinburgh University. Professor Paterson is often not listened to by ministers and educationalists to the detriment of school pupils, because his observations tend to focus on the interests of those pupils rather than those of the ministers and educationalists.

Interviewed on BBC Radio Scotland on Tuesday morning, he made two salient points. First, that because most coursework was cancelled earlier this year, ‘a lot of the information that teachers would normally have on students’ progress during the year before the exams has actually been suspended this year’. As such, ‘we’re actually in a worse position now than teachers were last year’.

Teachers were, in the professor’s estimation, ‘being forced to start from scratch’. After being ‘told to abandon coursework’ they were now ‘expected to do new coursework that’s not even yet been announced’. Ultimately, Scotland’s schools will be ‘more than half way through the school year before teachers know what they will be able to use’.

Professor Paterson also grabbed the third rail of Scottish politics: how the education system fails — and fails the worst-off. Whereas ‘an army of tutors’ had been drafted in south of the border and disadvantaged pupils had benefited from a ‘much more concerted supply of laptops’, Scotland ‘unfortunately has not put the effort into providing that distanced learning support that it could have done’.

Creating fair circumstances for the exams to take place was not beyond the wit of Solomon, but there aren’t many Solomons employed in Scotland’s education bureaucracy. ‘It would take more than Scotland seems to be capable of doing,’ the academic told the BBC, ‘but in theory it could be done.’

It won’t be done, though, because it goes against the reigning ideology in Scottish education: ayebeenism. It’s aye been this way. It’s pointless trying to push back and point out that it hasn’t aye been like this; that Scottish education once prided itself on excellence for all children, regardless of their parents’ means. Old-timers and London Scots still talk about the days when our schooling was ‘the envy of the world’. Scarcely anyone up here talks like that anymore. Instead of trying to improve the lot of the poor, the prevailing philosophy is equality in mediocrity.

Today a Scottish education gives every child, no matter how rich or poor, the chance to benefit from a system as unimaginative for itself as it is unambitious for its pupils. You can’t say fairer than that.

Comments