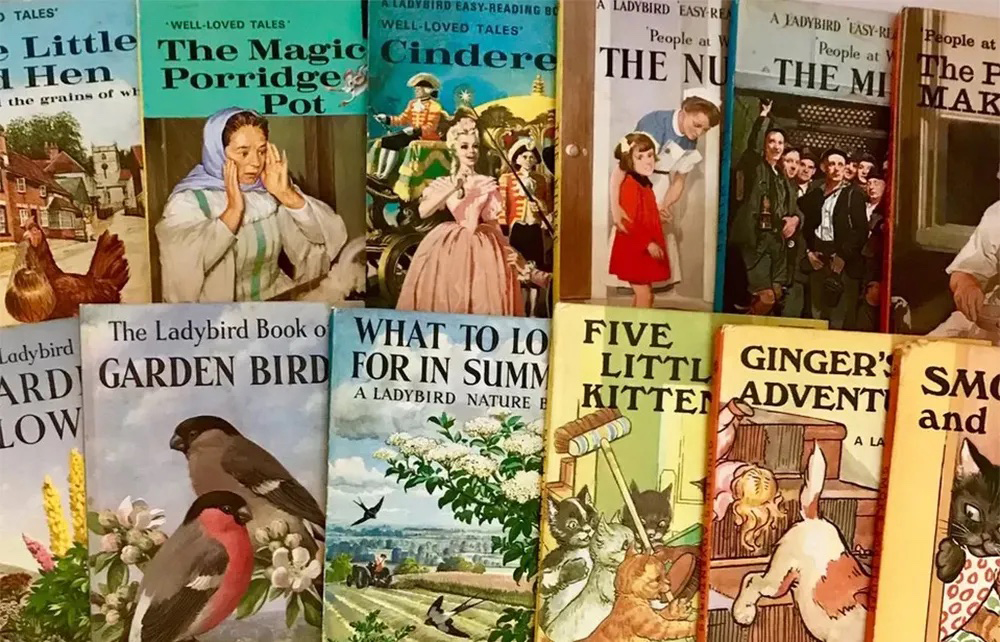

The first editor I worked for was Charles Moore and, like many of his old and ageing former staff, I still think of him as the boss. We’re like sleeper agents, the remaining skeleton crew of the old Daily Telegraph, ready to rise up at any moment and defend the right to hunt with hounds. I’m programmed to obey, so when Lord Moore recommended, in this magazine a few years ago, a series of out-of-print Ladybird history books for children written by a man called Lawrence du Garde Peach, I instantly bought the lot for my son: L. du Garde Peach on Cleopatra, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Kings Alfred, Richard and Henry VIII.

From Ramses II through to Queen Victoria, the fiercest humans are portrayed as giant babies

Now I owe Lord Moore more than ever. Without L. du G. Peach and his Adventure from History series acting as guide and comparison, I might have begun to think modern children’s history books were normal, that it was necessary for the past to be not just dumbed down, but entirely infantilised.

The easiest way to explain how dramatically children’s non-fiction, especially history, has changed is to compare the illustrations. Over the past 70 years every character in children’s non-fiction has been subject to a form of head inflation. Quite literally, their craniums have been expanding decade by decade until they’ve all taken on the proportions of six-year-olds. From Ramses II through to Queen Victoria, in books even for teenagers, the wisest, fiercest humans are portrayed as giant babies. And because they look like infants, they behave like infants.

In Meet the Ancient Greeks by James Davies (a bestseller), Alexander the Great sticks Post-it notes on the countries he’s captured. Gotcha! ‘Hydra Schnydra!’ says Heracles as he hacks away at the Hydra. In Davies’s Meet the Romans, one gladiator locked in mortal combat with another says: ‘Nice net… I’m really scared!’ His opponent replies: ‘At least I’m not wearing a fish on my head!’ ‘Phwoar,’ says bobble-headed Horus to Hathor, the Egyptian Goddess of love in Meet the Ancient Egyptians.

In his book on Ancient Egypt for readers of roughly the same age, du Garde Peach writes: ‘The great civilisation of Egypt had lasted for five thousand years, and it has been said of it that it had lit the torch of civilisation in ages inconceivably remote, and had passed it on to the peoples of the West.’

Mr du Peach’s regular illustrator for the Adventure History series was John Kenney, who painted dramatic watercolours, and I can’t tell you how surreal they look these days. Normal adult humans! With ordinary-sized adult heads! Bizarre. Kenney’s Cleopatra is snake-hipped and sultry, his Alfred the Great manly, though perhaps a little blow-dried, even under proper attack from deadly Danes. On the days when I’ve starved my eight-year-old of all other forms of entertainment, he turns to du Garde Peach. I watch as he studies Kenney’s battle scenes, a child in the right relation to the adult past.

Am I comparing like with like? Davies’s books might be intended for readers a year or two younger than du Garde Peach’s, but in children’s non-fiction today, every one of the history books are in the Davies vein. Horrible Histories: Cruel Kings and Mean Queens – ‘Read all about the nasty bits!’ Totally Chaotic History: Ancient Egypt Gets Unruly!’ Watch as bug-eyed King Tut runs screaming from a crocodile. Does this make the past ‘fun’ and ‘relatable’? If I were a 21st-century child it would give me the proper heebie–jeebies to think that civilisation had been dominated by toddlers into fart jokes.

In Waterstones on Islington Green, I had an unexpected burst of sympathy for the eco-idiots of Just Stop Oil who this week chained themselves to the stage during a performance of Les Mis. There’s something delightful about fake revolutionaries disrupting a play about real ones. But then these are graduates of the Davies school of history. It’s not impossible that they actually think that having tantrums and throwing paint is the right way to effect social change. We had L. du Garde Peach’s William the Conqueror around the house when I was young. I remember peering at Kenney’s watercolour of the Battle of Hastings and being shocked to see that he had actually painted a Norman arrow half-sunk into Harold’s eye socket. I had imagined, until then, that I might be brave in battle. It was instructive.

Presiding over the whole children’s section of Waterstones is my least favourite series, a set of books called Little People Big Dreams, in which humanity’s highest achievers are portrayed as toddlers with vast, morose, wobbling heads. Marie Curie, Darwin, Anne Frank. I’ve written before about their corrosive message: all you need to succeed is a dream, no graft or luck required. This time, it was the Little People’s proportions that struck me most. The strong subliminal message I received, under the baleful eye of a five-year-old Charles Dickens, was that ‘cute’ has now superseded all the traditional virtues, and that nothing can really be said to be truly good unless it’s also cute. The Little People have pride of place on the shelves and also their own special Waterstones stand which I know does not come cheap. Little People, Big Dosh.

Conversely, if cute is good, then nothing presented as cute can really be bad. Also available at Waterstones, in the children’s history section, is a jolly cartoon book by Emilie Dufresne called Pride in Sport (reading age seven-11 years), which celebrates gay athletes throughout history. The martial arts fighter Fallon Fox, a man who identifies as a woman, is pictured as a smiling young cartoon girl. He has a speech bubble: ‘It’s not about the genitals… it’s not the chromosomes. It’s the thing located inside the cranium!’ What the real Fallon actually said, after he cracked two female opponents’ skulls, was: ‘See, I love smacking up TERFS in the cage!’ If only John Kenney had done the illustrations, that would be a real education.

Comments