Lost boys, lost women, lost civilisations, lost causes — the romantic ring of the word ‘lost’ is media gold. So when the British Museum announced last autumn that it had acquired 103 ‘lost’ drawings by Hokusai, one was tempted to take it with a large pinch of salt.

How do 103 drawings by Japan’s most famous artist simply disappear? The answer is, surprisingly easily. Hokusai’s works have never commanded the sorts of prices a draughtsman of his calibre would be expected to fetch, not even in Japan. His art was designed to be affordable: in his day, you could buy a print of ‘The Great Wave’ for the price of a double portion of noodles — and still stretch, if you were lucky, to a side order of ‘A High Wind of Yeijiri’. Even today his prices lag far behind those of equivalent masters. The British Museum picked up this trove of drawings for £270,000, with Art Fund assistance. That wouldn’t buy a line of a Leonardo drawing or half a sketch by Rembrandt. In the art market, low prices mean a low profile. So after these drawings last appeared at auction in Paris in 1948, they slipped from view.

Where have they been all this time? Somebody must know but nobody’s telling. Tim Clark, former head of Japanese art at the British Museum and a Hokusai specialist, was gobsmacked when in October 2019 the dealer Israel Goldman brought the drawings in; he had never heard of them. That they were genuine there was no doubt, as they bore the seal of Henri Vever, the French art-nouveau jeweller and Japanese-art collector whose 8,000 woodblock prints, sold during the first world war to the Japanese industrialist Matsukata, came to form the basis of the Tokyo National Museum’s print collection. Previously dismissed by Japanese officialdom as ephemera, ukiyo-e prints were carried to Edo like coals to Newcastle.

How do 103 drawings by Japan’s most famous artist disappear? The answer is, surprisingly easily

It was six years after Vever’s death in 1942 that this group of postcard-sized brush drawings disappeared into a private collection, to resurface at Piasa in Paris in June 2019 with a high estimate of €20,000. They went for more than six times that, but it was still a steal. Piasa refused to divulge the consignor’s identity, beyond saying that it was a French collector. Saleroom confidentiality is as sacred as the confessional.

The drawings relate to a group of similar ‘block-ready’ drawings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston — also ‘lost’ until 1988, this time among the museum’s own holdings — and some rough sketches in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. They were made for a publication ambitiously titled the Great Picture Book of Everything: the title cartouche on page two is held up by a boy with a fan and an old man with a flywhisk, offering the reader their services during what promises to be an encyclopaedic marathon. But the book never got off the starting blocks, perhaps because the artist fell out — not for the first time —with his publisher. By 1829, when he made these drawings, the 70-year-old Hokusai was becoming increasingly picky about reproduction quality, insisting on using only top-notch block cutters and sending back substandard blocks to be recut. Whatever the reason, the fact that the book was never published saved the drawings for posterity, as they would have been cut through to carve the blocks.

Publishing’s loss has been art’s gain. The drawings are an eye-opener, not just because of the undiluted energy of their original ink lines but because of their extraordinary range of subject matter. Hokusai had long outgrown the ukiyo-e repertoire of actors, courtesans and erotica; in later life he was driven, like Leonardo, by an urge to bring the whole of nature — animal, vegetable, mineral, human, divine — within his grasp. If a picture book of everything was to be created, he was the man for the job.

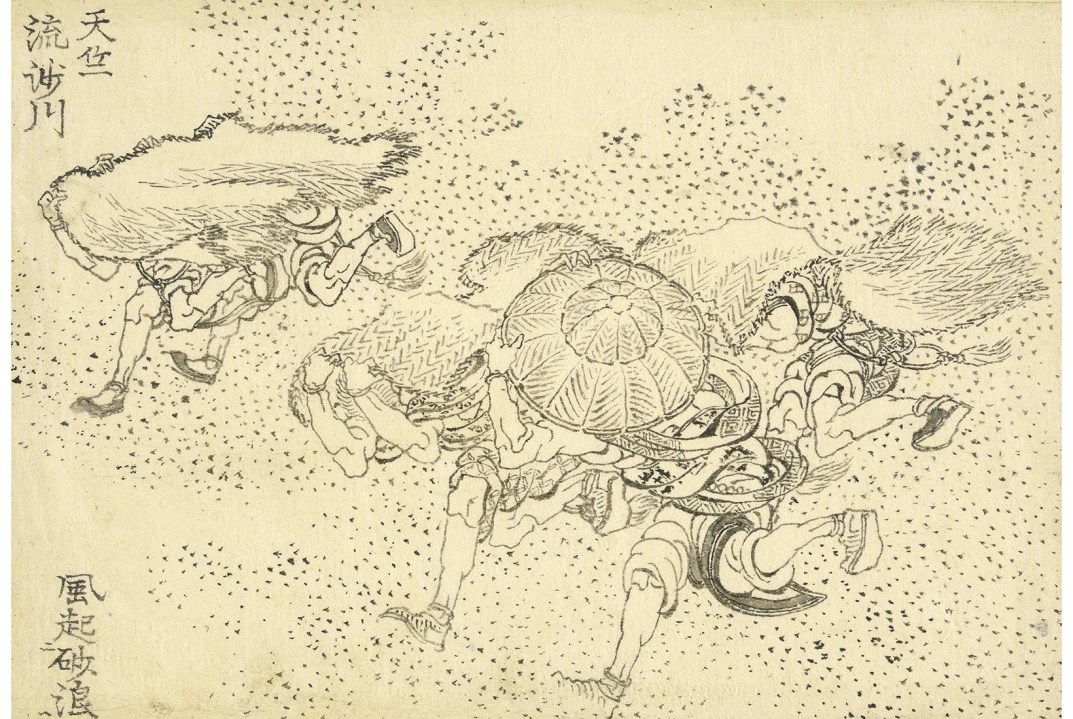

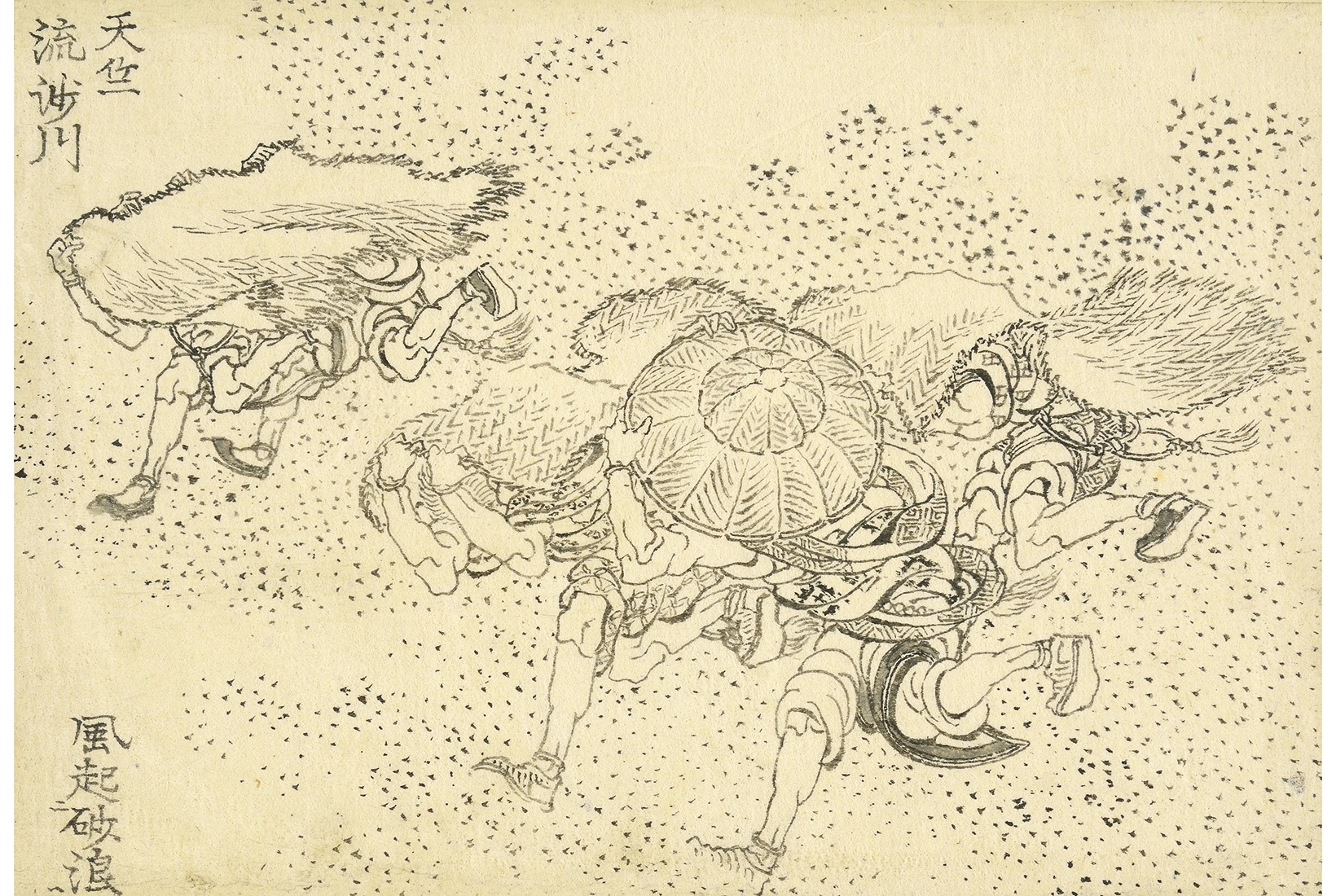

Before the Meiji Restoration of 1868, encyclopaedias were popular with armchair travellers. For two centuries the Japanese had been under lockdown, not only barred from foreign travel but unable to leave their towns or villages without permission. To feed their hunger for knowledge of the outside world, Hokusai had to rely on antiquated sources: a parade of foreigners in national costume includes a ‘Southern Barbarian’ — Portuguese to us — in 17th-century dress. But mostly he relied on imagination. His crumpled Indian elephant resembles a Claes Oldenburg soft sculpture, but his brush injects life into all it touches. His six Indians running from the rain with mats and baskets over their heads are universal figures — there’s only one way of legging it from a downpour the world over — and his Heath Robinson-esque reconstruction of the ancient Chinese art of making rice wine is none the less vivid for being absurd.

What’s most striking, though, is the modernity of his freeze-framing. Decades before the camera was a twinkle in the Japanese eye, Hokusai was cropping images like action shots. In one drawing of a sea monster attacking a ship, only the monster’s snout and the ship’s prow are visible; in another of Monk Chuanzi throwing Jiashan into the sea, the dunked half of Jiashan’s body is cut off by the frame. A month before he saw the drawings, Clark wrote a blog on the British Museum website proposing Hokusai as the father of the manga comic — though the soppy saucer eyes of modern Japanese manga characters owe more to Disney — and wondering whether he wasn’t also ‘one of the most important inventors of modern animation’. If so, forget Disney: the true heirs to Hokusai are the brilliantly inventive Looney Tunes animators. In his autobiography Chuck Reducks, the legendary Looney Tunes director Chuck Jones mentioned that he modelled Wile E. Coyote’s ragged tail on Japanese images of ocean waves. He clearly had one particular wave in mind. If Hokusai’s nine-tailed spirit fox looks suspiciously like a cousin of Coyote, DNA evidence may yet emerge to prove it.

For a new generation of artists and animators, this rediscovered cache of drawings straight from the artist’s brush — viewable on the British Museum website, with an exhibition and book planned for September — is ripe for pillaging. For Hokusai scholars, it fills a lacuna in the artist’s biography previously regarded as a career low point. In 1829 Hokusai suffered a minor stroke — successfully treated, he tells us, with hot sake and lemon — and lost his wife; the following year he wrote to his publishers begging for work. But far from languishing, these drawings show the 70-year-old artist at the peak of his powers, limbering up for the climactic Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (c.1831) that would usher in the most productive period of his life.

‘Ever since I was six, I have been obsessed with drawing the shapes of things…’ he would later write in the preface to One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, ‘but nothing I produced before the age of seventy is worthy of note.’ By the end of his life, the artist signing himself ‘Old Man Mad about Drawing’ was reporting ‘a strange thing… my characters, my animals, my insects and my fish seem to be escaping from the paper’. They’ve been trying to make their escape ever since, and it’s only the freeze-frames that stop them.

All 103 Hokusai drawings are now available to view on the British Museum Collection online.

Comments