Is it possible for a government minister to give a speech that is not a “keynote address”? That was my first thought upon reading Maria Miller’s speech at the British Museum last week. My second thought was remembering the old saw that any time a government minister talks about “culture” it is sensible to reach for your Browning. Thirdly, I recalled that Maria Miller is the kind of Commissar whose officials think it sensible to threaten journalists.

So I suppose that I was predisposed to think poorly of her speech on the economic importance of the arts.

Well, it was still a rotten speech that lived-down to these low expectations.

Given the portentous title “Testing Times: Fighting Culture’s Corner in an Age of Austerity” Miller’s speech was banal and platitudinous where it wasn’t simply stupid and meretricious. Other than that it was fine.

It is hardly news that the so-called “creative industries” (a term that merits a place on John Rentoul’s Banned List) are “worth” a lot of money these days. As Martin Bright says, the arts have been making this plea for importance for a long, long time now. This, as Martin implies, demonstrates a certain weakness. It is as though the spending of public money on the arts can only be justified or otherwise defended on economic grounds. The arts have, understandably if also regrettably, connived in this process.

Breathes there a Whitehall man with soul so dead who to himself hath only said, what is this worth, this art, this all? Indeed there is. Ms Miller is but another who can put a price on many things but appears blind to their value.

Her speech was a depressing, if familiarly so, tour of deadbeat government banality. It was also appallingly written. For instance, we no longer have tourists, we have a “visitor economy” instead. Then there was this:

You will all have seen the GREAT campaign which was launched last year… Heritage is GREAT… Creativity is GREAT… Innovation is GREAT. All these themes market Britain to the rest of the world as precisely what we are – GREAT.

But when I started this job one theme particularly caught my eye: Culture is GREAT. British culture is perhaps the most powerful and most compelling product we have available to us. The most compelling platform upon which we can stand.

Shakespeare wept.

Befitting a former advertising executive – advertising being perhaps the lowest form of art – Miller advises us that

[A] proper grasp of the potential economic impact of culture would serve us all well. Culture is an intricate web of activity, where blossoming stars in regional theatres have the potential to become the next generation of British Oscar winners; and where the Paul Smiths of tomorrow can be inspired by what they see at the V&A and go on to become global icons.

Can you have a non-intricate web? Who thinks Paul Smith, a talented cloth-cutter, is a “global icon”? (And is a fashion designer, however good, really the pinnacle of artistic excellence?) For that matter, is an Oscar winner actually more “valuable” than a regional theatre stalwart, blossoming or not?

Unwisely, Miller (whose remit, I should point out, does not run across the whole of the UK) attempted to make a virtue of her emaciated “vision”:

Culture cannot be seen in isolation at a time of unprecedented economic challenge. Everyone has to play a part in our efforts to reduce the deficit, my Department is no exception. Do we want to be seen to inspire our children or leave them with a mountain of debt?

As though that’s the only choice! It makes no sense the other way round either: Do we want to leave our children with a mountain of debt or be seen to inspire them? Then again, is it more important to be seen to inspire our children (think of the children!) or to actually inspire them? Who the hell can tell?

I’d have more – that is, some – respect for Miller if she gave the slightest indication of knowing what the arts are for (to the extent they are even for anything). But she does not.

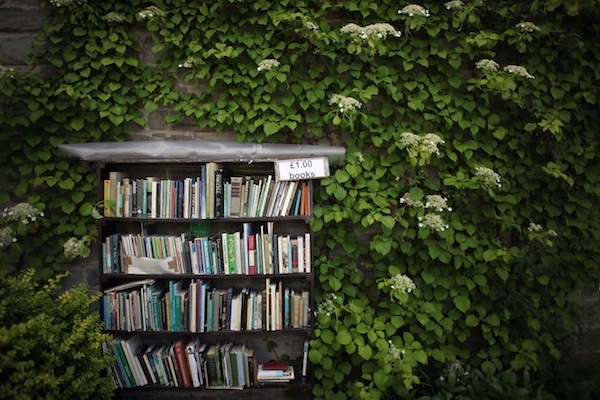

It is telling, I think, that the words beauty and pleasure are absent from her speech. But without beauty and pleasure what is the point of the arts? We do not visit museums or theatres or purchase books or concert tickets because doing so is part of our duty in an Age of Austerity; we do so because these things improve our lives and give us pleasure. Investment – ie, money, whether public or not – in the arts is not something the value of which can be determined by consulting a spreadsheet. It is not a matter of maximising economic returns but rather of supporting work that seems interesting or important and trusting that, in time, that work will find a public.

But supporting artists does not require any kind of short-term return. Suppose, for instance, that JK Rowling’s work, supported in her early years by the Scottish Arts Council, had not proved such an astonishing success and that, instead, it would be 50 years before children discovered – or rediscovered – her books. Would that (hypothetical) initial failure to earn a return have made her a bad “bet”?

Of course not. There is a respectable case for abolishing the public subsidy of the arts but it is one of those areas in which the costs of withdrawing subsidy surely outweigh the benefits to the public purse of doing so. This is so because the cost – a few hundred millions a year – is trivial in the context of a government budget that;s north of £600bn.

Meanwhile, the increasing bureaucracy involved in arts spending – the hoops through which one must jumpy before getting any public money – is such that a smaller and smaller percentage of each additional pound spent actually goes to the provision of art. It goes instead to officials and outreach staff and marketing and all these other things. I suspect the proportion of “creatives” in the “creative industries” is smaller than once it was.

That’s evidence, for sure, that public money produces perverse incentives. Better to hire an expert form-filler who knows how to tap the public purse for cash than to hire a talented theatre director! The government distorts the market, however you choose to measure or define the market.

Still, a more confident – even, damn it, a better government – would be better than this. It would view arts spending as a series of god-knows-what-will-happen punts some of which may pay-off in years to come. It would certainly not suggest it should be in the business of “picking winners”. You hand over the cash and you hope that good work comes of it.

Not everything that merits support will give pleasure or prove economically useful. But that’s fine. We know much less about what will eventually prove valuable than we think we do.

Government ministers sort of know they should value art for arts sake but they plainly are uncomfortable making that argument. That’s a depressing commentary upon our times. But the cost of public subsidy is trivial and, by god, it would be nice if, just for once, a Culture Minister could remember that pleasure, not economic activity, is the chief point of their bloody ministry.

Comments