A visitor returning to Britain after 30 years could easily be fooled — by the sight of privatised buses and by the replacement of heavy nationalised industries by hi-tech business parks — into thinking that Britain has been transformed from a sub-socialist society into a dynamic free enterprise economy. In some ways that may be true, yet paradoxically the public sector is actually larger relative to the rest of the economy than it was in the dying days of the last Labour government. In 1979 the government accounted for 45 pence in every pound spent in the UK economy. This financial year it will be 47.5 pence.

What are public sector workers doing if they are no longer mining coal, driving buses or making steel? A huge and growing number of them are engaged in regulatory activities. We have gone from a blue-collar public sector to a white-collar one. The state does not work on the shop floor; it is employed upstairs in the compliance department, in health and safety and in human resources. Nowhere demonstrates the change more than Castle Morpeth in Northumberland; once a coal-mining district, it has developed an economy which revolves around state bureau-cracy. Government employers, most significantly the local authority and the Inland Revenue, account for 57 per cent of all jobs in the district.

Conservative and Labour governments of the past 30 years have been well aware of the negative effect of the public sector on productivity and economic growth. A study for the European Central Bank quantified the effect: for every 1 per cent increase in the proportion of a country’s GDP made up by the public sector, GDP can be expected to fall by 0.13 per cent. The Thatcher, Major and Blair governments all sought to improve economic performance through privatisation and contracting out. But what none of them did was to tackle the inefficiencies of those parts of the economy which remain in the public sector.

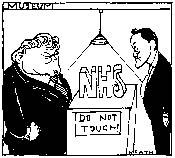

This has to be the top economic priority for the next government. Management in the public sector is a bizarre labyrinth of regulators and inspection agencies which are often effective at identifying failure but which are miserably poor at doing anything to correct it.

No private business would set about trying to improve the performance of staff by setting up an inspection department based 200 miles away from where most of the staff are based, and using it to name and shame poor performers publicly. Yet that is what the government does all the time, for example with Ofsted, and with the 50 or so quangos which operate in the area of healthcare.

We need to sweep away many of these regulatory bodies and substitute more direct management structures. Headteachers should be responsible for their staff, not a team of Ofsted inspectors who breeze in and out and who have no ongoing relationship with the school. Chief executives of hospitals should have the responsibility and freedom to manage their operations; they should not be spending their time trying to tweak everything to hit the targets set for them by outside agencies – a factor in the poor performance of Stafford hospital revealed in Robert Francis’s report last week.

Management in the public sector is hamstrung by employment legislation. Employers must go through a five-point procedure of verbal warnings, written warnings and meetings with trade union representatives before they can dismiss chronically underperforming staff. The Gershon report found that it cost the Department for Work and Pensions an average of £34,000 to sack staff and the Foreign Office an astonishing £160,000. But hiring staff is no better. The Prison Service has a 39-point protocol for recruiting new staff, including a duty to ensure the diversity of the selection panel.

Before anyone new can be appointed consideration must be given as to whether the new post could be filled by an employee made redundant in another part of the Prison Service – who may well be somebody who has already underperformed. The public sector is becoming like a vast country house run by bumbling old retainers.

Much of this legislation needs to be swept away: in a dynamic economy employees have to expect to change jobs, not have their posts preserved for them until retirement. So, too, must go national pay bargaining, which, for example, obliges hospitals in Tyneside to pay nurses as much as those in Surrey, where the cost of living is so much greater and the alternative jobs on offer more highly paid. Equal pay audits, which have cost councils £2.8 billion to implement, must be abolished. No government will be able to afford much longer to ignore the issue of public sector pensions: servicing the debt on public sector final salary schemes is already costing the taxpayer £45.2 billion. The failure to change final salary schemes into cheaper, money purchase schemes is not just costing money: it is creating a perverse incentive for public sector staff to remain in unchallenging jobs rather than seek new opportunities in the private sector.

These are reforms which staff employed in privatised industries and contracted out service have already been through – to huge efficiency gains. It is time the revolution was extended to the remaining public sector.

Ross Clark is the author, with Neil O’Brien, of The Renewal of Government: A Manifesto for Whoever Wins the Election, published this week by the Policy Exchange.

Comments