In 1931, a 23-year-old Englishman called Henry ‘Gino’ Watkins returned from an expedition to the white depths of the Greenlandic ice cap.

In 1931, a 23-year-old Englishman called Henry ‘Gino’ Watkins returned from an expedition to the white depths of the Greenlandic ice cap. He was hailed as a precocious talent, even as a worthy successor to Fridtjof Nansen, who had recently died. When Watkins died the following year, during another expedition to Greenland, King George remarked on the tragedy of his death, and Stanley Baldwin wrote that ‘If he had lived he might have ranked . . . among the greatest of polar explorers’. Yet Watkins had only just begun to establish himself, and his reputation swiftly faded.

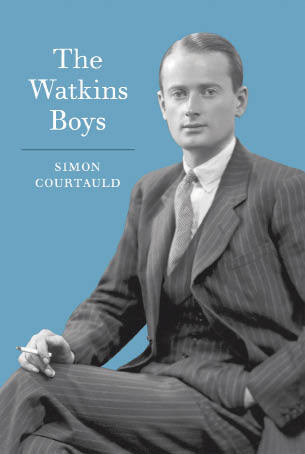

Simon Courtauld recreates Gino Watkins’s expeditions to Greenland by way of seven finely drawn character studies — of Watkins and his companions. At first glance, Watkins seems an unlikely candidate for polar heroism: a socialite, given — in London — to decadence; willowy and beautiful to the point of effeminacy. Yet he was also charismatic, ambitious and, on occasion, entirely ruthless.

When Watkins sailed, it was only 40 years since Nansen had made the first crossing of the Greenlandic ice cap, from the east to the west coast. The population of Greenland was mostly confined to small settlements in the south. Watkins’s was the first English expedition to go up the east coast to the Arctic Circle, a wild region of scrappy beaches, forbidding cliffs, and, above, the glittering ridges of the ice cap. Watkins had some laudable official aims: to help open up the first commercial air route over the Arctic to North America, to map the mountains and coasts of east Greenland and to monitor the weather on the ice cap throughout the year.

He achieved some of this, though Courtauld, refreshingly enough, is less interested in meteorological readings and whether the guns jammed or the pemmican froze than in the crucial question of why on earth a group of rich amateurs went to Greenland in the first place, to drag sledges up glaciers and be lashed by winds of 100 mph, to be lonely and afraid.

This enquiry is entirely gripping, and allows Courtauld to speculate intriguingly about the drives and urges of an interwar generation who profoundly distrusted the establishment, did not want to ‘play the game’ and yet, equally, did not want to languish in idleness. Watkins was in double retreat — from ‘all that,’ as Robert Graves called it, and also from a debilitating family background: his father had been absent and financially dissolute; his mother had killed herself when he was 21; his two siblings were given to bouts of deep depression. One of his companions in Greenland was Freddy Spencer Chapman, equally dispossessed: ‘who from birth had been a virtual orphan,’ ‘restless as well as rootless, seeking new challenges both mental and physical. He would strive against all the difficulties he could find and overcome them.’

Another of Watkins’s ‘boys’, August Courtauld (the author’s uncle) took the idea of retreat to an even higher level, and became an Arctic anchorite, buried alive in the snow. He had volunteered to spend a winter alone on the ice cap, looking after a weather station. After a few months of digging himself out of the tent each day to check the weather readings, he left his shovel outside, so for six weeks he was trapped inside, his fuel supplies dwindling. Apparently unperturbed, he read through a library of about 30 books, and tried to keep his mind on higher things. When his friends finally found him, he was ‘still perfectly sane, bolstered by his faith in God and by an enviable inner calm.’

A few years after Watkins died, his contemporaries W. H. Auden and Louis MacNeice travelled to Iceland. Their aims were not remotely exploratory, in the traditional, map-enhancing sense. Instead, they explained, they wanted to escape ‘the backchat and self-pity’ of London, to ‘mortify/Our blowsy intellects before we die,’ to discover the ‘lost’ within them that could not be found in England. In this fascinating and unusual book, Courtauld suggests that this was the real quest of Watkins and his men.

Joanna Kavenna is Writer-in-Residence at St Peter’s College Oxford and the author of The Ice Museum: In Search of the Lost Land of Thule.

Comments