When Scotland’s rugby team landed in Invercargill for the World Cup, they were greeted by a piper in full Highland fig and a cheering crowd of more than 500 New Zealanders, bedecked in tartan and waving St Andrew flags. The significance of both welcome and dress went beyond sport or nationality. Two important currents of modern life were at work, the ancient ability of the British empire to create societies in its own image, and the new power of the heritage industry to invent the past. Together they have made it necessary to update the old formula, ‘history is written by the winners,’ with the qualification, ‘but heritage is created by the losers’.

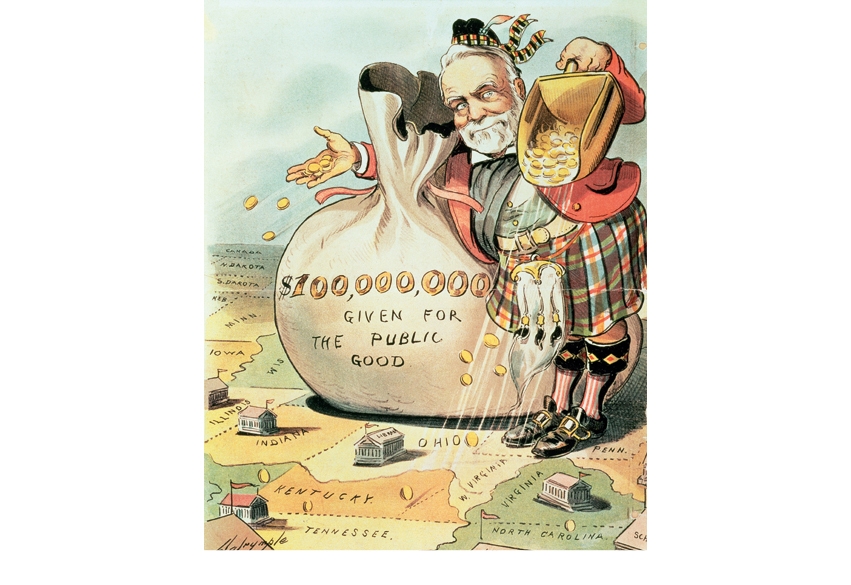

As Professor Devine demonstrates in his sharply written history of the overseas migration of the Scots, the unmistakable winners were the Presbyterians, who as slavers, financiers, shippers and industrialists surfed the imperialist wave further and more profitably than any other cultural group in the United Kingdom. Best known were the likes of Willliam Jardine, half of eponymous Jardine Matheson, and kingpin of the opium cartel that created Hong Kong, Andrew Carnegie, whose American steel company made him the richest industrialist in the world, Thomas Glover, co-founder of Japan’s Mitsubishi engineering business, and Thomas Sutherland, chairman of P&O shipping and founder of the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank.

But behind them came a host of others who relied first on superior education — five universities to England’s two in the 18th century — then on networking through innumerable Caledonian and Burns clubs, and finally on the sheer weight of accumulated capital to advance towards wealth and authority. The world encirclement of Scottish finance at the end of the 19th century prompted one Australian banker to complain that Edinburgh was

honeycombed with agencies for collecting money, not for use in Australia, but for India, Canada, South America — everywhere almost, and for all purposes on the security of pastoral and agricultural lands in Texas, California, Queensland and Mexico.

The losers were the Catholic Highlanders, representing perhaps five per cent of the estimated three million Scots who have emigrated since 1800. Cleared violently or voluntarily from their lands to make room for sheep or deer, it is their fate that generates the fiercest emotions.

The sense of injustice, rarely far from one of victimisation, is undiluted by the fact that in their new homes Highlanders were as assiduous as other colonisers in displacing native inhabitants. In Tierra del Fuego, in a township called Cameron, I recently found the grave of John MacDonald, a shepherd, who had died 12,000 miles from his birthplace in Skye. There was a double poignancy to his lonely headstone because it revealed he had been killed by indigenous Yaghans protecting their hunting grounds against his sheep.

Devine is an admirable historian, acerbic in judgment, and a pleasure to read, not least in pursuit of the heritage actors: ‘It is not unusual at Scottish gatherings in the [American] South’ he writes, ‘to see some wearing combined Highland dress and Confederate garb, a kind of Bonnie Prince Charlie meets Robert E. Lee lost-cause combo.’

But To the Ends of the Earth has a wider purpose. Not only does it fill a serious gap left by the tendency of imperial historians to dwell on the political and capital power wielded in Westminster and the City of London, it points to the ruthless edge that the Presbyterians gave to the British empire. Even David Livingstone, virtually sanctified by his Victorian admirers, worked public opinion as shrewdly as any politician to win support for his campaign against slavery.

But empire exacted a hidden cost. The sheer flood of talent overseas from Scotland’s 19th-century population of barely four million could not be sustained. Even before the waning of imperial power, the rapid success of German competitors revealed that the industrialists responsible for Scotland’s manufacturing wealth in shipbuilding, coal-mining and chemicals, had become second-rate, lacking initiative and drive, the very qualities shown by Scots making their fortunes abroad.

To the Ends of the Earth ends with a paradox, however. It is the kilt not Calvinism, heritage not history, that Scotland’s nationalist government plays on to draw in tourists and build business opportunities among the Scottish diaspora. And the link offers other possibilities. In the 20th century, it was the exiled Fenians and homeless Zionists who brought an independent Ireland and Israel into being. In the 21st, the tartan connection may do the same for Scotland.

Comments