I was on a train when it happened. I was bent double with my head between my knees, gasping for air and unable to speak. The Surrey matriarch sitting opposite leant forward to ask me if she could help. I imagine she thought that I was choking, or perhaps suffering cardiac arrest. In fact, I was laughing. Laughing so hard I couldn’t stop. And the more I wanted to stop, the worse it got. It was painful. My lungs rasped and the muscles in my sides contracted of their own free will. I was no longer master of myself, so you might say that I was in ecstasy. It was certainly exhilarating.

I regained composure and explained myself to this kind woman. She looked stern; her immaculate curls bristling slightly at my wildness. She reminded me of the serious gentleman who had sat next to me some years before during a performance of the Merry Wives of Windsor, starring Leslie Phillips as Falstaff. He told my chortling mother to ‘stop laughing at Shakespeare’.

Back on the train, it was all Tom Sharpe’s fault. I had been reading Wilt. Specifically the section where the gin-fuelled Henry Wilt, the everyman anti-hero of the book, attempts to stuff a strong-willed sex doll, mocked up in his wife’s clothes and lipstick, down a manhole. Wilt is test-running a scheme to murder his insufferable wife. Wilt’s failure with the doll is total, and an elaborate farce blossoms from this blackly hilarious beginning.

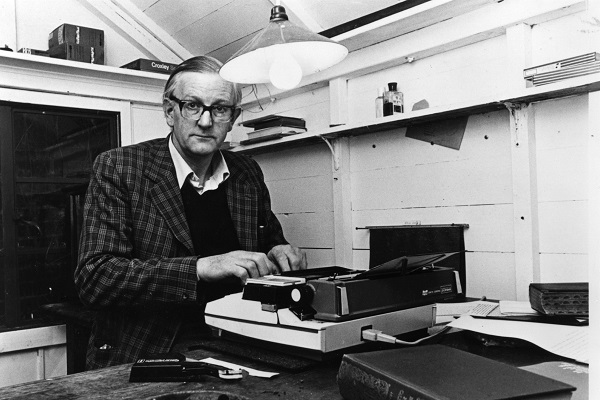

Tom Sharpe, who died yesterday aged 85, wrote several very popular novels between 1971 and the mid-80s. They defy the categorisation favoured by publishers and much ‘book chat’. They are not trashy genre fiction; but neither are they literary. Sharpe is often marked as a descendent of Evelyn Waugh; but, while Decline and Fall and the Basil Seal novels share common ground with Wilt and Porterhouse Blue, there is nothing in Sharpe’s oeuvre to match the literary achievement of the Sword of Honour trilogy. Indeed, he never attempted anything so ambitious.

Sharpe, though, was not a trivial novelist. Riotous Assembly and Indecent Exposure, his first two books, savage Apartheid South Africa, where he had lived from 1952 until being deported in 1961. Both books begin darkly and gradually burst into uproarious farce. This was Sharpe’s method. Elite education received similar treatment in Porterhouse Blue and The Great Pursuit. The latter book also touched on another of his concerns: the deleterious effects of “literature”. This was the subject of Vintage Stuff. The class system and “Englishness” were given both barrels in The Throwback, Ancestral Vices and Blott on the Landscape.

All of these books have glorious comic moments; but none are as consistently funny and strangely real as the Henry Wilt books, which cover marriage, family, career, ageing and sex. These themes are familiar to many contemporary authors; but no one matches Sharpe’s humour and pace. His satire is vicious, but it’s not always slap-stick. We first meet Henry Wilt in the early ‘70s, when he is a lecturer in ‘liberal studies’ at a godforsaken tech in East Anglia, where he teaches psychopathic meat-packing apprentices Mill on the Floss and other unsuitable classics. Change is afoot. The progressive techniques we know and love today were taking root. Sharpe (who became a liberal arts lecturer soon after returning from South Africa) demolished the new fashions. A staff meeting in Wilt sees Dr Board ridicule the incomprehensible jargon of his trendy colleague Dr Mayfield. It is Michael Gove versus The Guardian, only better.

Sharpe was more than a gag-merchant; but, having said that, he was bloody funny. I bet he’s got the Almighty in stitches.

Comments