I was notified of my appointment with Pervez Musharraf by a text from his PR man: ‘General sahib has granted your request and wishes to see you in the afternoon.’ At the entrance to a gleaming skyscraper with views of the Burj Khalifa, I was greeted by a security guard in black sunglasses: ‘Welcome sir! You have 45 minutes.’

We ascended the elevator up to the penthouse, and were soon standing in the drawing room of Pakistan’s former president-dictator. The marble floors were strewn with Persian rugs; the walls were adorned with army mementos and Mughal paintings. The sound of ghazal music wafted through the air – as did the smell of cheese samosas.

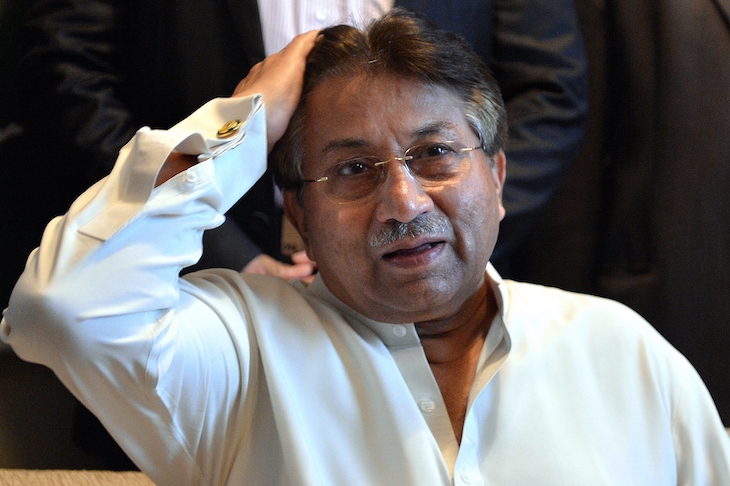

Musharraf entered, accompanied by one of the small dogs he reputedly adores. In a subdued voice, suggestive of his advancing age (he is 79 this year), he told me that he is still preoccupied by politics and plans to go back to Pakistan for further campaigning. When I suggested that his time was up, he grew insistent. ‘In my ten years, I realised that Pakistan has the potential to stand on its feet. I know it because I have done it. No one else knows it … The Sharifs and the Zardaris [his political opponents] must go.’

On October 12, 1999, Musharraf, then Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff, was on a flight from Colombo to Karachi. The airport personnel had received orders from the Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, to prevent Musharraf from landing, and instead to redirect his plane to India. The army’s response was a coup which enabled Musharraf to declare a state of emergency and seize power as chief executive. Having nominated himself as President in 2001, his position was legitimised when he won the role in ostensibly democratic elections in 2002. After the Pakistan Peoples Party, formerly led by Benazir Bhutto, won a majority of seats in Parliament in the 2008 elections, Musharraf was forced to resign to avoid impeachment, and went into self-imposed exile. He returned to Pakistan in 2013 to contest the election, but was disqualified and indicted on charges including his alleged involvement in Bhutto’s assassination and high treason for his imposition of emergency rule in 2007. In 2016, he was allowed to travel to Dubai for ‘medical treatment’, and he has been living there ever since.

Musharraf is happy to talk international politics too. In the wake of the 9/11 bombings, he declared his support for the United States in the ‘War on Terror’. But what about now that the global balance of power has shifted? When I ask him if Islamabad now favours Beijing over Washington, his reply is, ‘Yes. Pakistan’s future is no longer dependent on Washington alone. It’s a multipolar world now and China’s emergence should open up vast trade opportunities for us.’

With China’s increasing popularity, there is a corresponding disillusionment with the US and its leader. ‘Trump is a confused man. He doesn’t understand our problems…Has there been any effort from our side to revive Pakistan’s plunging ties with the White House? No one visits Washington now.’

On the other hand, Musharraf claims to have forged ‘great relations’ with world leaders. In particular, with Vladimir Putin, whom he claims to have persuaded to sell seven Mi-17 helicopters to Pakistan, denying them to India. ‘I told Putin, “Look, Mr President, if you think India will remain with you, you are mistaken. The Indians have leanings towards the United States. They also don’t wish to see the Chinese gaining access to the Indian Ocean. Let us rise above that.” And I got them – I got those damn Mi-17s.’ However, this does not seem to have prevented Russia continuing to negotiate the sale of Mi-17s to India.

Musharraf is less enthusiastic when discussing his relationship with Tony Blair. ‘I found him to be fidgety. A soul that invested too much on mundane matters and someone who wasn’t too comfortable in giving answers to his own media.’ Perhaps, we might speculate, it was Blair’s perceived tilt towards India on the conflict in Kashmir that caused this discomfort. Or his government’s successful lobbying to suspend Pakistan’s membership of the Commonwealth in 2007 and condemnation of Musharraf’s ‘determination to lock up political prisoners, his suspension of the constitution and his restrictions on the media’.

On my way out I ask, ‘Are you returning to Pakistan? There are cases pending against you.’

‘Inshallah! Very soon,’ he answers. ‘I shall face them like a true soldier.’ Time will tell whether Musharraf will live up to his boast and join old hands like Silvio Berlusconi in the ranks of politics’ great survivors. His latest step has been to resign from his party, the All Pakistan Muslim League, and demand a guarantee that he will not be arrested upon his return to the country.

But even the canniest survivors should not expect their people’s goodwill to last forever.

B. J. Sadiq is a British Pakistani writer and author of Let There Be Justice: The Political Journey of Imran Khan (Fonthill Media, 2017)

Comments