Daniel McCarthy has narrated this article for you to listen to.

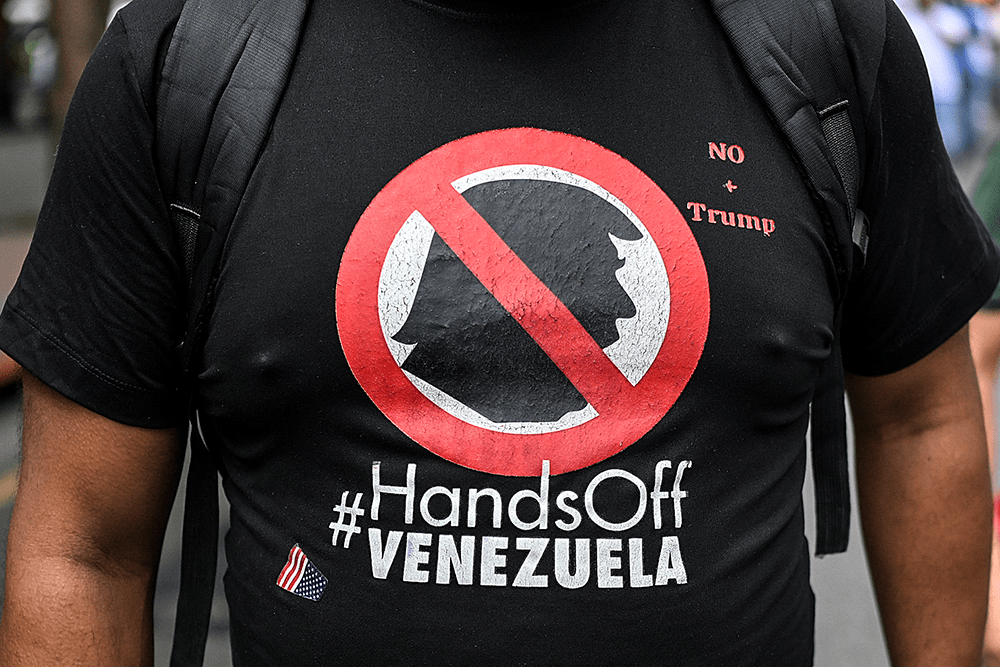

Few Americans find much to celebrate in the Iraq War or the intervention in Libya. Regimes were successfully changed, but what came after Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi was civil war, regional instability and mass migration that exported many of those nations’ troubles to their neighbours. Now the Donald Trump administration wants to do to Venezuela’s despot, Nicolas Maduro, what George W. Bush did to Saddam and Barack Obama did to Gaddafi. But that will also do to the Americas, including the United States, what the war on terror did to the Middle East, North Africa and Europe.

The chaos and population flows that regime change sets off are a boon to drug networks and human-traffickers

The foreign policy blunders of Bush and Obama gave Trump one of his strongest campaign themes in 2016. His first term was distinguished by his success at keeping America out of new wars. He has never been allergic to the use of force – as the ghost of Iranian commander Qasem Soleimani can attest – but even when he’s involved the US in a new Middle East conflict during his second term, Trump has stopped short of pursuing regime change. He struck Iran’s nuclear programme and promptly ended Israel’s war with the Islamic Republic. Does it make sense to depart from what’s worked for him to take up aims that didn’t work for Bush or Obama?

In that first term, Trump attempted a kind of pantomime regime change in Venezuela. An opposition politician, Juan Guaido, unilaterally declared himself ‘interim president’; Trump recognised the claim. Mike Pompeo, then secretary of state, followed up by appointing an unreconstructed neocon, Elliott Abrams, as US special representative for Venezuela. Abrams was deeply involved in Reagan-era support for anti-communist paramilitaries in Latin America, including the Iran-Contra scandal.

While Abrams is no longer in post, the administration’s steps so far this year – destroying Venezuelan boats that the White House says are ferrying drugs to the US, approving CIA operations in the country, sending warships within striking range – indicate that regime change is still on the agenda.

But if the experiences of Bush and Obama are not warning enough, Trump should consider what happened when Ronald Reagan, and Jimmy Carter before him, intervened in El Salvador. The results were the same as we’ve seen earlier in this century: civil war sent waves of refugees and immigrants abroad, including to the US, where some of the new Salvadoran communities formed gangs, notably MS-13, now one of the most violent in America.

The tension in the Trump administration isn’t just between foreign-policy hawks and doves – it’s between the hawks and the immigration restrictionists. Nor does the intervention strategy make sense as a tactic to stop illegal drugs, especially fentanyl, from reaching the States. The chaos and population flows that regime change sets off are a boon to drug networks and human-traffickers. It’s true that Maduro and his predecessor, Hugo Chavez, have caused some migration by remaining in power, but the people fleeing because of socialism are often middle class and freedom-loving. War uproots every-one, especially the poor.

Despite saying during the 2016 election that George W. Bush should have taken Iraq’s oil, Trump is probably not contemplating an invasion to seize Venezuela’s considerable petroleum resources. He’s conducting a ‘maximum pressure’ campaign to make an example of Maduro. Trump wants to show there are rewards for America’s friends and painful punishments for its enemies. Maduro’s fate will be a lesson to anyone else in Latin America who thinks of making a foe of Washington. At least, that’s the theory – but the US has a long history of throwing its weight around in Latin America and making more enemies in the process.

The model Trump should adopt isn’t Reagan’s strategy in Latin America but the one that won the Cold War in Europe: stabilising America’s friends and allies and helping them prosper, thereby heightening the contrast between life under freedom and under socialism. Seeing that contrast inspired Europeans to liberate themselves.

If Latin Americans want freedom, as Argentines have demanded in the elections that put Javier Milei in office and then strengthened his party in the legislature, they can achieve it just as eastern Europeans did. On the other hand, the examples of those places where the US relied most on force during the Cold War are overwhelmingly negative. Even the great triumph of Reagan-era political warfare in Afghanistan defeated a Soviet puppet only to create conditions that would bring the Taliban to power and give al Qaeda a haven from which to attack the US. A Pyrrhic victory if ever there was one.

The Trump administration’s interest in toppling Maduro preceded Marco Rubio’s tenure as secretary of state, and sources say it’s unfair to blame Rubio for the neocon tilt of Venezuela policy. But if there’s a war, it will be his at least as much as Trump’s, and if it goes badly, he will get the blame – not least from the President. Rubio has earned respect from many in the MAGA movement who once thought of him as a Bush Republican: weak on immigration, neocon in foreign policy. He risks proving his detractors right if he embraces a regime-change programme left over from the days of Pompeo.

As for Trump, he sees force as another form of leverage in negotiations. He won’t bomb allies in trade talks, but he will use American military might to change the way adversaries think. And if he’s not about to start a war with China, he’s fully prepared to demonstrate what he can do on Maduro. Making an educational point rather than changing the regime may be his objective. But there’s a constituency in the Republican party which wants more than that, and Trump likes to give everyone in his coalition something they have their hearts set on. In this case, though, he can’t please the hawks without displeasing immigration restrictionists as well as doves.

Obama, Bush II and Reagan have shown that when America tries to overthrow other regimes, the result is mass migration that greatly affects Europe and the US. Regime change abroad also has a habit of leading to regime change at home.

Comments