The warnings from around the world about the scale of the UK’s government debt crisis keep flowing in. Following last week’s warnings from the IMF and European Commission about the scale of the UK debt crisis, credit rating agency Fitch has described the UK as the AAA country most vulnerable to a downgrade. The table at the bottom of the page shows the European Commission’s forecasts for Government deficits as a share of GDP for next year. The UK beats IMF bailout case, Latvia, to head the league table with a deficit level almost double the EU average. The Commission estimates that the UK’s total debt will have almost doubled from 43% of GDP in 2007 to over 82% in just 3 years, moving the UK quickly towards the top of the EU debt league table.

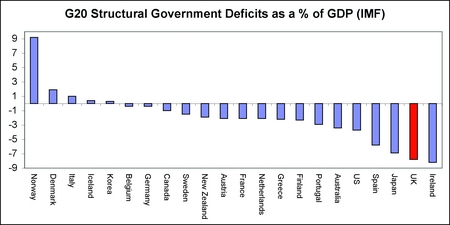

The IMF’s most recent warnings to the UK on Government deficit levels focused on the severity of structural debt problems that the UK has relative to most other developed nations. The chart above shows that the UK is rivaled only by Ireland in having the worst structural government finance position in among the G20. A structural deficit is the amount of government borrowing that would likely occur outside of recession – ie the underlying gap between tax revenues and government spending levels.

How did the UK end up with the worst Government debt position in the world so quickly? Two very basic beginner’s mistakes in economic management were made over recent years.

The first was to assume that tax revenues from the credit and housing bubble were sustainable and increasing government spending on that basis. When economies have a boom driven by household borrowing and house price rises, tax revenues from banks, property taxes and capital gains tend to soar. When the inevitable downturn comes, they normally fall away quickly. The European Commission estimates that 60% of the government deficit increase is driven by the dive in tax revenues. This pattern has been repeated many times over the past 50 years, hence treating tax revenue increases and debt accumulation with care in a boom is a core part of good economic management practice around the world now. Only a true believer in the end of boom and bust would ever rely so heavily on the permanence of this transitory surge in tax revenues to fund a much larger government sector.

The second basic error was running a large deficit at the height of the boom. The UK hit the downturn with close to the largest running deficit in the world. As the European Commission point out, this left the UK unable “to pursue a looser fiscal stance without compromising budgetary sustainability”. Failing to save for a rainy day in the face of the one of the biggest ever run ups in personal debt and banking leverage left the UK uniquely weak to meet the global downturn.

When the huge hit of absorbing the losses of the banks is added in, the UK is suffering from an increase in Government debt wholly unprecedented outside of wartime. Government debt levels have moved well into the territory more associated with IMF bailouts than an AAA credit rating, as the credit rating agencies are making increasingly clear.

The tidal wave of debt that Gordon Brown unleashed may have carried him across the threshold of No 10, but it is drowning the UK economy today.

EU Government deficit estimates as % share of GDP 2010

UK – 12.9

Ireland – 12.5

Latvia – 12.3

Greece – 12.2

Spain – 10.1

Lithuania – 9.2

France – 8.2

Portugal – 8

Poland – 7.5

EU Average – 6.9

Slovenia – 7

Romania – 6.8

Netherlands – 6.1

Slovakia – 6

Belgium – 5.8

Czech – 5.5

Austria – 5.5

Italy – 5.3

Germany – 5

Denmark – 4.8

Finland – 4.5

Estonia – 3.2

Comments