The latest movie to turn into a musical is Amélie, from 2001, about a Parisian do-gooder or ‘godmother of the unloved’. Some rate Amélie as the worst film ever made in France. Some consider it the worst film ever made. Our heroine is a 20-year-old waitress, a sort of proto-Greta, who plays truant from her restaurant job and wanders around Paris doing nice things to random strangers. Her inspiration is a box hidden by a child in her apartment 40 years earlier which she wants to restore to its original owner. Or, as the clunky narrator puts it, ‘Why is she holding that box like her future is inside it?’

Amélie’s odyssey brings her into contact with all kinds of misfits, pests and layabouts who belong in a magic realist novel. Her chief suitor is a brain-damaged drifter who collects mug shots abandoned in photo booths. She meets a fig merchant in the market who kisses each piece of fruit he sells. At work in her restaurant, she’s serenaded by a pretentious French scribbler who tells her, ‘Ahm collecteeng people’s lacks and dislacks for an epique poem.’ We hear an excerpt from his masterpiece. ‘The night was,’ he declaims. Later we learn that this is the entire poem. A character named the Glass Man tells Amélie that his skeleton is too brittle to endure physical contact. ‘I’d shake your hand but mine would break.’ Is this character a mere lunatic or a make-believe figure from a cartoon?

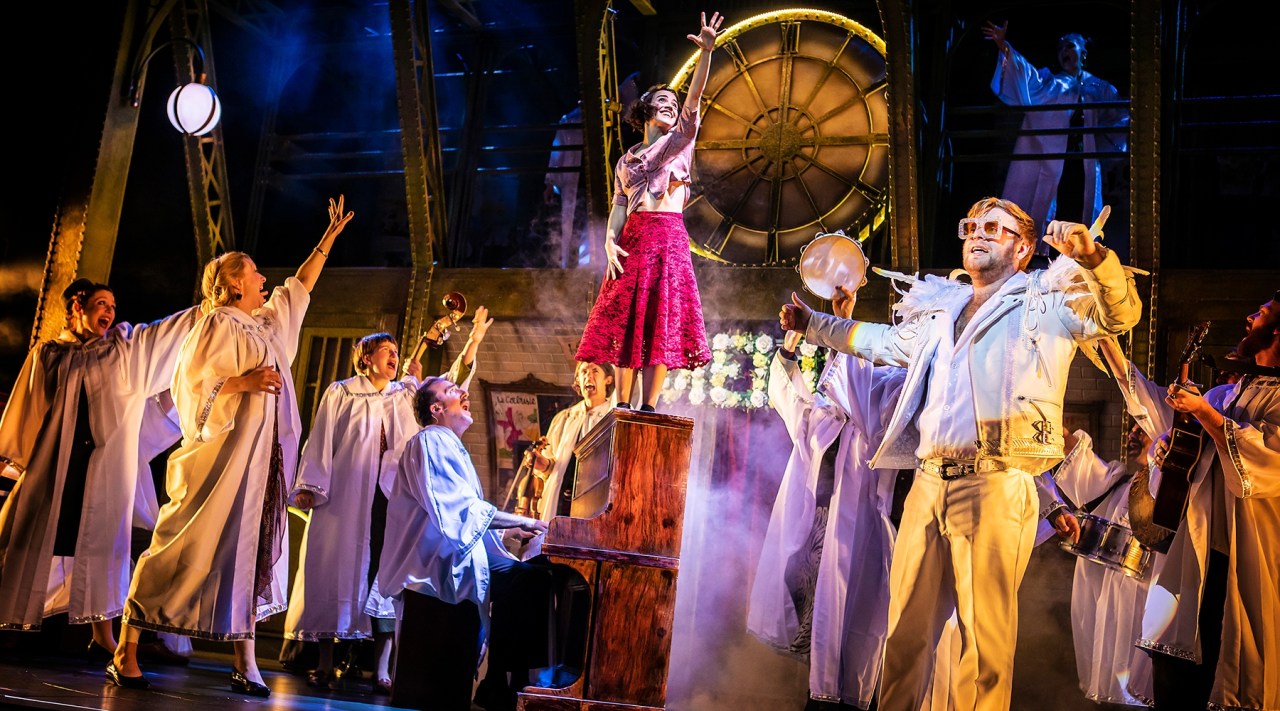

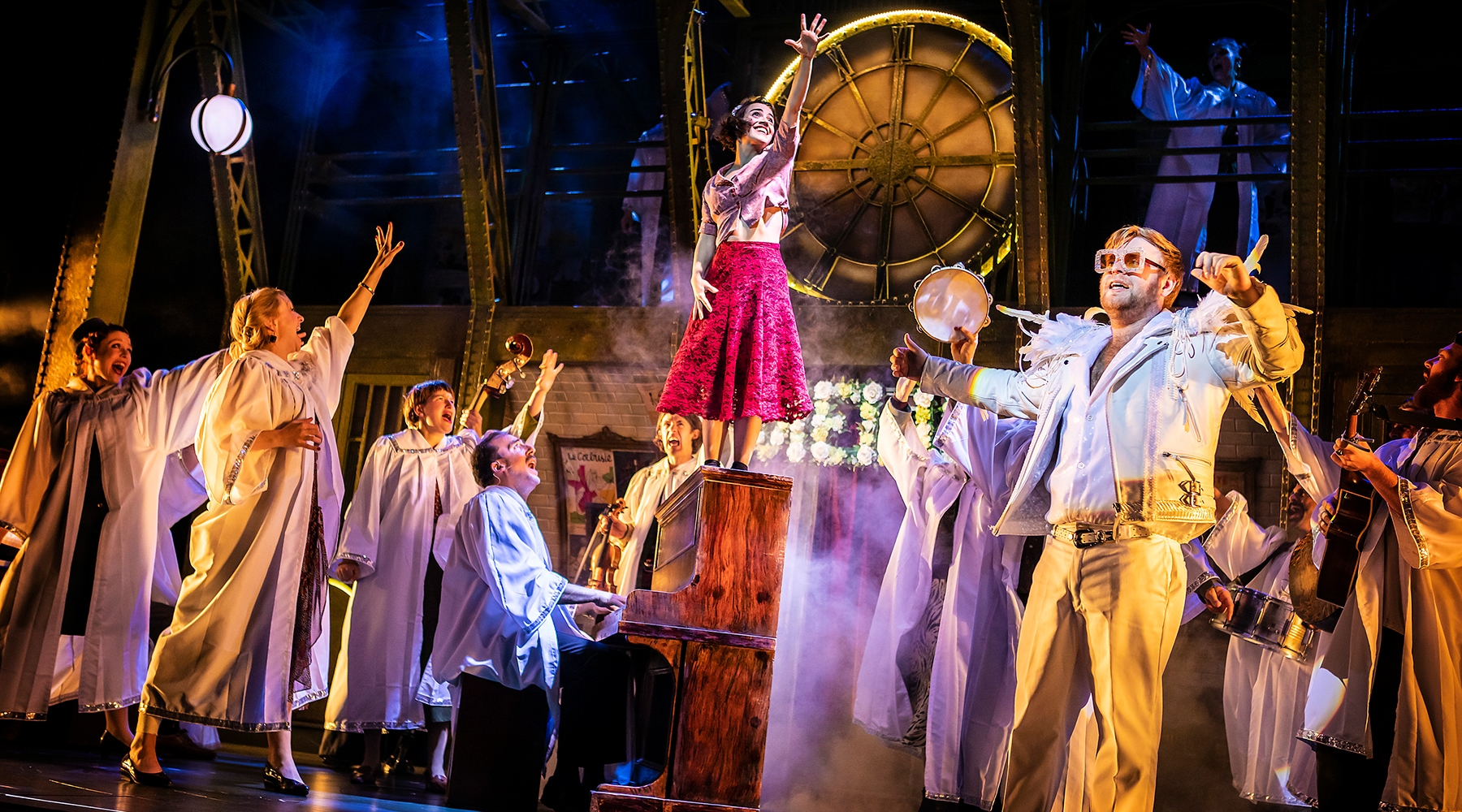

If you want to disengage your brain for two hours, this is your perfect night out

The blurring of fact and fiction make it hard to invest any emotional interest in Amélie or her prattling escorts. In its favour, the show has decent costumes and stylishly atmospheric lighting. The dancing musicians fling themselves into their routines with gusto. So if you want to disengage your brain and enjoy two hours of colourful kitsch tomfoolery, with no real story or character development, this is your perfect night out.

Amazing stuff at the Harold Pinter Theatre. A debut play by an untested writer has been given a world première in the West End. That’s highly unusual. But the good news ends there. The humourless script by New York writer Amy Berryman is static and vastly over-laden with exposition. It takes 75 minutes for the plot to start. (Why didn’t anyone notice that at the first read-through?)

The setting is a woodland shack where Stella (Gemma Arterton) and Bryan (Fehinti Balogan) are getting back to nature in the aftermath of some vague eco-apocalypse. Meanwhile the campaign to colonise space is accelerating and the couple are visited by Cassie (Lydia Wilson), an astronaut, who is also Stella’s twin. Space exploration is the family trade and they recall with pride the exploits of their father who went into orbit many years earlier.

Finally, the story begins. Cassie asks Stella to offer herself as a guinea pig on Earth while Cassie leads the first mission to Mars. Stella’s blood samples will furnish the boffins with vital comparative data about Cassie as she hurtles towards the Red Planet. But there’s a kink in the tale. Stella once worked for Nasa too. In fact, she designed the Martian space pod, code-named Walden, on which her sister will live. Later she quit the agency and took a job waiting tables in a beer cellar. Seriously. That’s what we’re told: one of the world’s greatest engineers has become a barmaid.

The chatty, meandering script develops into a playroom fight between the rival sisters over their different futures. Will Stella and Bryan be content in their love shack with a baby on the way? Or will intrepid Cassie feel more fulfilled journeying to Mars even though she must abandon any hope of raising children? In fact, this detail is misleading. Some experts predict that Mars will be colonised by a crew of women, carrying frozen sperm, who will impregnate themselves on arrival. Thus, the first man on Mars will be born there. A spot of homework might have improved this script. And Berryman should have invested a larger creative effort in the third character, Bryan, who comes across as a dim but well-meaning domestic subordinate. A member of staff, effectively.

Berryman adds a stern warning in the play script that he ‘should be played by an actor of a different racial, ethnic or cultural background than Cassie and Stella’. Fair enough. But why didn’t Berryman give him a distinctive heritage and make him, say, Jamaican, Bolivian, Moroccan or Pakistani? Perhaps she couldn’t be bothered. As long he wasn’t white, that was fine. One is entitled to conclude that Berryman considers all ethnic minorities interchangeable. That isn’t necessarily a sign of bigotry because indifference is not the same as contempt but it’s strange for a playwright to have so little curiosity about cultures and nations other than her own. And it’s even stranger to advertise her insularity in the text of her debut play. She seems a bit behind the times.

Comments