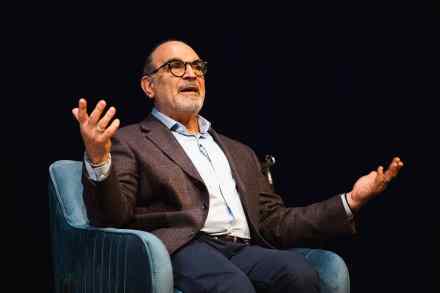

It’s no Jerusalem: Jez Butterworth’s Hills of California, at Harold Pinter Theatre, reviewed

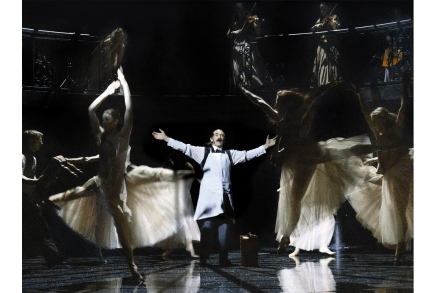

Fifteen years after penning his mega-hit Jerusalem, Jez Butterworth has knocked out a new drama. The slightly baffling title, The Hills of California, refers to a hit by Johnny Mercer (the US songwriter not the MP for Plymouth) and it suggests American themes and locations. But the show is set in a knackered old Blackpool boarding house in the 1970s, where three sisters are waiting for their elderly mum to croak. It takes an hour of chit-chat to explain what’s happening. When the sisters were little, their ambitious mother forced them to perform song-and-dance routines in the hope of launching them as kiddie superstars on the new medium of television.