The Ottoman Empire inspired great travel books as well as great architects. Travellers like George Sandys, Richard Pococke or the Chevalier d’Arvieux in the 17th and 18th centuries were curious, erudite and less arrogant than their 19th-century successors.

The Ottoman Empire inspired great travel books as well as great architects. Travellers like George Sandys, Richard Pococke or the Chevalier d’Arvieux in the 17th and 18th centuries were curious, erudite and less arrogant than their 19th-century successors. Like cameras, they recorded monuments, encounters, manners and customs. They can make the reader feel that he or she is there, in Smyrna or Beirut, at that time.

Ottoman travel writers on Europe, however, are far fewer. There was no equivalent of Jerusalem or Baalbek to lure Ottomans to the West, as Europeans were lured east in search of religious shrines and classical antiquities. Nor could they worship as easily in uniformity-obsessed Europe as Christians and Jews could in the multi-faith Ottoman empire. In Europe, travelling Muslims in flowing robes might be jeered at, spied on or worse: there was a massacre of Muslims in Marseilles in 1620.

Evliya Celebi is the great exception. Born in Istanbul in 1610, the son of the sultan’s chief goldsmith, he became a Koran-reciter and muezzin, later a favoured courtier of the ferocious Sultan Murad IV. He had completed, by his own calculation, 1,060 Koran recitations since his childhood, and could recite it ‘without fault’ in eight hours.

Evliya has been described as ‘the Ottoman Pepys’. Calling himself a ‘world traveller and boon companion to mankind’, since youth he had only ‘one wish’: to travel. He wrote:

I made it my ambition to examine at first hand the monuments of the seven climes that have excited the admiration of the men of knowledge and insight.

Before he died in Cairo around 1683, he had written, in what he calls ‘shameless detail’, a ten-volume Book of Travels based on notes taken during his journeys.

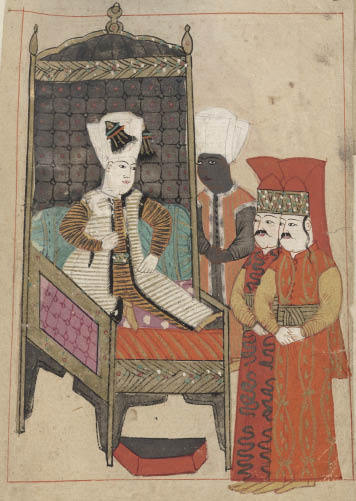

This is the first modern edition in English, brilliantly produced, with excellent maps and illustrations, by the Olympus of travel publishers, Eland Books. It is selected and translated by Professors Robert Dankoff, founder of ‘Evliya studies’, and Sooyong Kim. Evliya wanted to give a complete account of the empire, as well as of his own travels. Pages abound with vivid, and often unique, descriptions of, for example, oil wells in Baku and cats in Ardabil, court protocol in Crimea or acrobatics in Diyarbekir. He reminds us of the prevalence of mixed cities in the Ottoman empire; compared with the wealthy Christians of Athens, its Muslims were ‘a despised lot’.

Evliya frequently rhapsodises about ‘boy sweethearts’ embracing without fear in the hammams of Bursa, or ‘catching the hearts of lovers in the traps of their flowing locks’ in the cafés of Cairo: ‘It is considered youthful exuberance and not improper behaviour.’ ‘Evliya the unhypocritical’, as he repeatedly calls himself, never married.

Despite the charm and colour of his style, however, and the range of his travels, Evliya can be unreliable. He describes the tomb of Suleyman the Magnificent, ‘may his earth be sweet’, but not the adjoining tomb of his wife Hurrem — affirmation of her unique status as wife of a reigning Sultan. He says Galata tower, built by the Genoese in 1346, was constructed 100 years later by Mehmed the Conqueror. His knowledge of Europe was imperfect. He believed Dunkirk to be a country, and Bohemia to be ruled by Sweden, and claimed to have taken part in an imaginary Tartar raid on Amsterdam in 1663. For Evliya, ‘All Franks have the itch’ (syphilis), while in Egypt ‘the pudendum of a man who has sex with a crocodile exudes a musk-like perfume for an entire week’.

During a visit to Vienna in 1665, in the suite of the Ottoman ambassador, he was impressed by the hospitals but dismayed by the sight of women talking to men:

The reason is that throughout Christendom women are in charge and they have behaved in this disreputable fashion ever since the time of the Virgin Mary.

He describes Saint Stephen’s cathedral as if it was a Greek church with domes, and claimed that it was decorated with rubies and turquoise. In other words, literary formulae replaced direct observation.

Evliya’s work has been called ‘the most monumental example of first-person narrative in Ottoman literature’, and he used the largest vocabulary of any Ottoman writer. Given his prejudices and credulity, however, it is unsurprising that most of the educated classes of the empire fell in love with French literature after 1850, few more so than the father of the Turkish republic, Mustafa Kemal.

Comments