Among the many photographs in this comprehensive history is one of a master in a clerical collar. He stares at the camera with a startled expression and looks out of place, devoid of the self-assurance of others alongside him. His name is J. W. Coke Norris, and it dawned on me slowly that this was the man on whom Rattigan had based the character of Crocker Harris, the dessicated classics master in The Browning Version, played in the film by Michael Redgrave, a play so close to Rattigan’s heart that he never had to make an alteration or change a line.

Like Crocker Harris, Coke Norris taught only the lower forms Latin and Greek, and was principally in charge of the school timetable. He took early retirement at 40. His occasional sermons would always open with the words: ‘As Thucydides tells us …’

Rattigan himself played in the 1929 Harrow cricket team. The following season, his last, he was mysteriously dropped from the XI, a failure that was to haunt him for the rest of his life. He had opened the batting with Victor Rothschild — an odd couple, though not as exotic as H. Boralessa and M. B. de Souza Girao, who opened for Harrow about 20 years ago, a Sri Lankan and a Portuguese. It may have been Boralessa who, after being caught brilliantly on the boundary at Lords, made a long detour on his way back to the pavilion in order to shake the hand of the Etonian who caught him.

Cricket and classics dominated the school for years. It was founded in 1572 by a local landowner, John Lyon, to provide a classical education for the poor boys of the parish and bring them up as gentlemen. Up until 1874 the statutes declared that all the boys must always talk to each other in Latin, never in English, even when playing games outside. A monitor was always around to make sure this rule was observed, and if not, the boys were punished.

All the early masters were classicists. If any mathematics was taught, it was limited to the theories of Euclid. History never went beyond that of Greece and Rome. Gradually during the 19th century, as the school grew, other subjects were introduced into the curriculum.

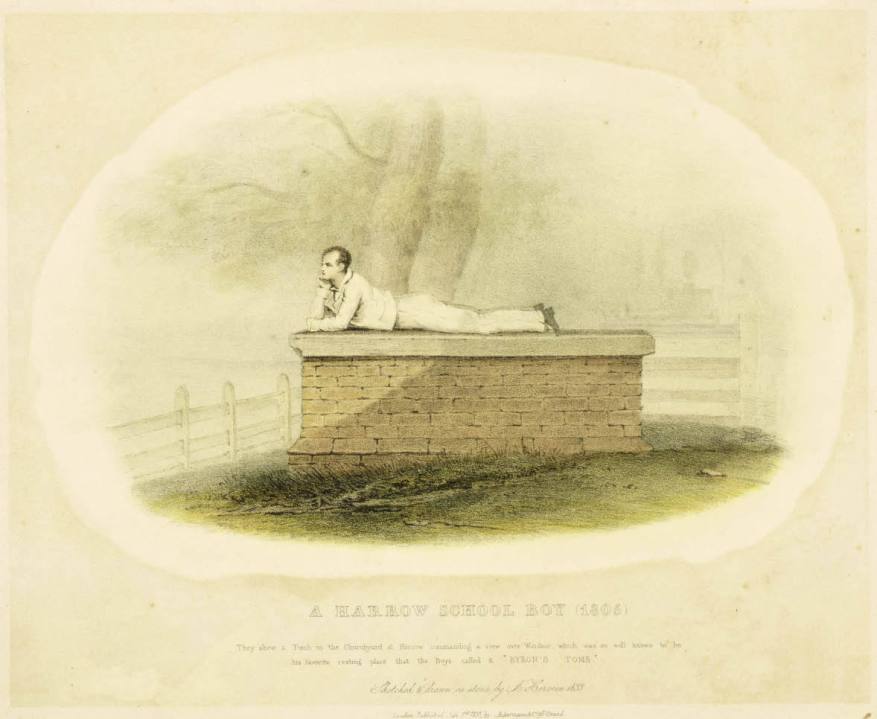

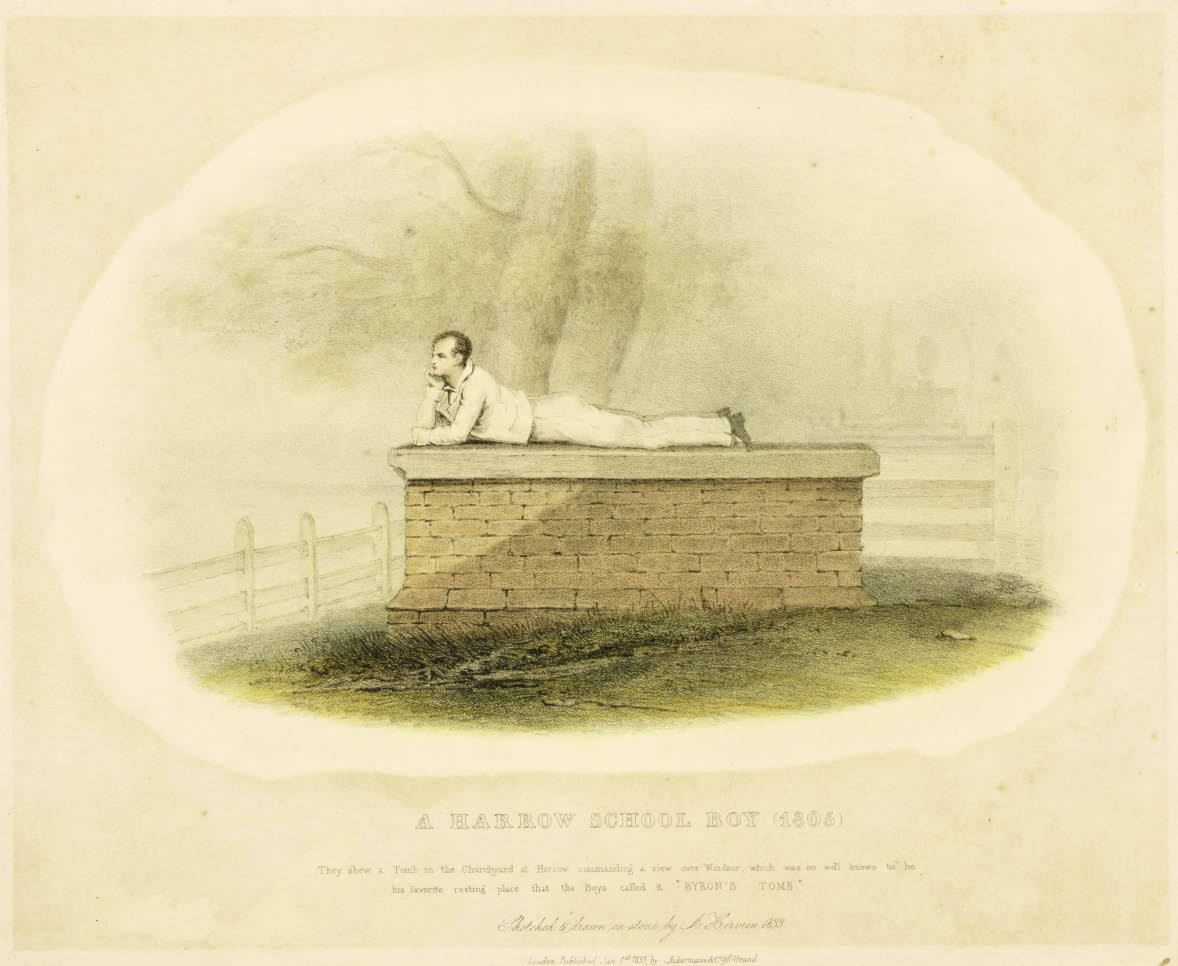

The craze for cricket began when they started playing Eton. The first recorded match in 1805, a few weeks before Trafalgar, featured Lord Byron. His captain didn’t know why he had picked him, but he had insisted on being chosen. Because of his lameness he was allowed a runner. In a letter he claimed to have scored 11 and 7 ‘which was more than any of our side except Brockman and Ipswich could contrive to hit’, but the score sheet reveals it was only 2 and 2. Harrow produced some of the most glittering cricketers of the Edwardian years and earlier, among them the dashing Hornby of ‘O my Hornby and my Barlow long ago.’

Two members of the 1887 team, F. S. Jackson and A. C. Maclaren, rose to be captains of England, both remarkable in their different way. Jackson, the ‘laughing cavalier’, captained in 1905 perhaps the most successful side ever fielded against Australia. He set a fine example himself, heading both the batting and bowling averages. When in 1921 Armstrong’s Australians swept aside the counties and crushed England in five successive test matches, Maclaren emerged like Cincinnatus from retirement to captain a motley side that he’d picked himself and win. A Harrovian, Falcon, took almost half the wickets.

Five Harrow cricketers (and six Etonians) have taken their own lives. The most tragic of them was Hugh Thompson, one of the most promising batsmen of his time, who at the beginning of the summer term when aged 17 was found hanging in a school bathroom, no one knows why. Another was Vibart, pictured in this book as the public school heavyweight champion, but equally famous as a cricketer. After a lifetime of drunken brawls he put an end to his violent career by swallowing a bottle of hydrochloric acid.

Harrow boxers were often brutal, and other schools dreaded facing them. One Harrovian, after leaving, knocked out the heavyweight champion of the world, the Canadian Tommy Burns, in a sparring match. Burns was never the same again and soon after lost his title to Jack Johnson.

The cult of the athlete was more intense at Harrow than anywhere else. Every boy’s ambition was to be elected to the Phil- athletic Club, which behaved with inordinate swagger and awarded itself privileges and powers denied to anyone else, including the school monitors. Masters were chosen as much for their athletic abilities as academic distinctions. One outstanding school pair remained unbeaten on the Fives court for three years, except in their weekly matches against two elderly members of the staff, the headmaster and the eminent historian, Townsend Warner, when they rarely won a game.

A corner of the school yard was converted into a racquets court, the first to be built outside the debtors’ prison where the game originated. Apart from that there was no apparent connection between these two institutions. Those who preferred hitting a softer ball invented squash, and in the 1930s the supremacy of Amr Bey, the Egyptian ambassador, whose ‘on-court manners’, according to Alan Ross, were ‘in keeping with his status’, and who ‘wrong-footed even as he smiled’, was only ever challenged by two Harrovians, Macpherson and the eccentric Gandar Dower, before he left for Africa to search for the mythical spotted lion.

Certain names recur down the years, generation after generation; the Blounts, at first as cricketers, then more recently the singer James Blunt (who dropped the ‘o’ from his surname); the Crawleys, cricketers and racquets champions; the Hadows. One Hadow disappeared down the face of the Matterhorn with several others during Whymper’s descent from the summit. Another won Wimbledon when on leave from his tea plantation in Ceylon.

Their school songs, most of them composed towards the end of the 19th century, were designed like Newbolt’s poetry to inspire them to live for something greater than themselves, and instill in them a love of games, school and country. Several were dedicated to athletic heroes of the time such as F. S. Jackson, for whom Churchill fagged, in later life the governor of Bengal. In Daphne Rae’s romantic account of the school as she remembered it, when married to an assistant master, she describes Harrovians abroad who had been

known to get together in deepest Africa, Indian tea plantations, on verandas of colonial bungalows, letting their voices rise to tell the world: ‘Forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit.’

Shackleton and his men sang the songs when trapped among the ice-floes of the Antarctic, though none of them had gone to Harrow.

According to the author, these songs remain with Harrovians for the rest of their lives, but when I asked Lord Lambton, by then resident in Italy, over a game of bridge if he still sang them in the bath or anywhere else, he dismissed the suggestion with a scornful laugh. Perhaps he was hiding his true feelings.

Would such songs, had they existed in his time, have lingered in Byron’s heart, another lordly Harrovian, in the years when he was a self-imposed exile in Italy like Lambton (and for slightly similar reasons)? He was known to descend to breakfast singing the latest operatic arias, but there was an occasion, one moonlit night in Genoa, while he sat with his friends on a balcony overlooking the bay, when some English crews from the merchantmen lying at anchor below them struck up with ‘God save the king.’ Its effect was ‘magnetic’, and Byron was no less touched than the rest. ‘This will never do,’ he murmured with a melancholy smile. ‘Tell it not in London. Little does his gracious majesty imagine what loyal subjects he has at Genoa, and least of all that I am among their number.’

These days Harrow, though still a great school, has rather lost its reputation for scholarship. The Byrons now are Brockets, and the glamour of the Eton and Harrow match has faded since the days when it was one of the highlights of the London season. It is odd that this history should come out so soon after the last one, by Christopher Tyerman, which could hardly be improved on. There is no hint in these pages of the scandals exposed by Tyerman, or the savage bullying and prostitute boys described by J. A. Symonds in the memoir of his time there, whose revelations to his father brought down Harrow’s greatest head- master, Charles Vaughan. The closest one comes to a scandal here is the failure of the Rugby XV to score a point in 1949.

This account of Harrow has some fascinating features, but the rather anodyne treatment, its division into sections and the multiple colour photographs make it appear more like a school prospectus than a serious history. Perhaps that is partly its purpose, as the school evolves into an international institution. Already versions of Harrow exist in Bangkok and Beijing. Next year another opens in Hong Kong.

Available from the Hill Shop on 020 8872 8212 or email shopmanager@harrowschool.org.uk

Comments