‘When Matisse dies,’ declared Picasso, ‘Chagall will be the only painter left who understands what colour really is.’ Wandering around this splendid show you can see exactly what he meant. Chagall never used colour for cheap effect, but to convey meaning and emotion. The effect of seeing so many of his works together is almost overwhelming — a symphony hung upon a wall. But these aren’t the romantic paintings of Chagall’s later years, the visions of young lovers floating over seas of flowers. These are the urgent artworks of his youth, made at a time of immense upheaval. By focusing on these early years, to the virtual exclusion of his later work, this fascinating retrospective casts Marc Chagall in an entirely different light.

Chagall — Modern Master is both autobiography and travelogue, charting his apprenticeship in Paris, from 1911 to 1914, and his return to his native Russia, from 1914 to 1922. These were the years that made him, but the restless art he made as a young man was quite different from the serene dreamscapes of his dotage. Chagall was born in 1887 and lived until 1985, and his remarkable longevity has skewed his reputation. His mature work is sublime — full of tenderness and wisdom, but this exhibition shows that, had he died in 1922, he’d be remembered as a more dynamic, expressionistic figure, an artist more in tune with our own troubled times.

Paris was Chagall’s university, introducing him to old masters (in the Louvre) and to contemporary artists such as Robert Delaunay, with whom he formed a close and influential friendship. Yet while other painters submerged their talent in the various isms of the age, Chagall learnt from Cubism and Orphism without forsaking his own vision. Liberated by distance and isolation (he arrived in Paris without any French, after a train journey of four days), he returned, in his mind’s eye, to Vitebsk, the Hasidic shtetl of his childhood. These pictures were never sentimental (he called Vitebsk ‘unhappy’ and ‘boring’) but they were full of feeling. As he said, he needed Paris like a tree needs water. The roots of his art, however, were his memories of home.

Chagall returned to Russia in 1914 for a brief visit, but was marooned there by the first world war. A desk job in St Petersburg saved him from the front. After the Revolution he was appointed arts commissar for Vitebsk (a ghastly title, worthy of our own Arts Council) but he was far too talented to become a mindless party apparatchik. ‘Why is the cow green? Why is the horse flying in the sky?’ asked his comrades when they saw his paintings. ‘What has that got to do with Marx and Lenin?’ ‘My knowledge of Marxism is confined to knowing that Marx was a Jew with a long white beard,’ retorted Chagall (his attitude to Judaism was as open- minded as his attitude to politics). In 1919 he resigned and went to work for the theatre in Moscow. In 1922 he returned to France, where he remained for most of his long life.

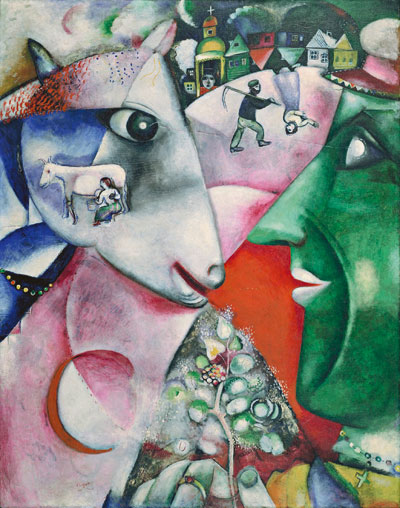

Chagall — Modern Master is a discreet triumph of curatorship. Zurich’s Kunsthaus has brought together a wealth of his early work from around the world: ‘Paris Through The Window’ from New York, ‘The Promenade’ from St Petersburg…. They’ve even reassembled the murals he made for the Yiddish Theatre in Moscow. The crowning glory is his iconic ‘I And The Village’, from MoMA, but there are some smaller surprises, too. Some of the most powerful pictures are from the Kunsthaus’s own collection. ‘Over Vitebsk’ depicts the artist as the archetypal Wandering Jew, stick in hand, sack on his back, sailing above his hometown like a forlorn but friendly ghost.

Zurich has always been a home from home for the Wandering Jew of Modern Art. There are several lavish late Chagalls in the Kunsthaus’s permanent collection, but his largest artworks in the city are the wonderful stained-glass windows he designed for the Fraumünster, one of Zurich’s most atmospheric churches. Chagall was in his eighties when he made these windows, but they’re bursting with vitality, flooding the aisles with tinted light. Back at the Kunsthaus, ‘Birth’, painted in 1910, depicts the joy and agony of childbirth. Just down the road, at the Kronenhalle, the restaurant where Chagall often dined, ‘Sunset’, painted in 1974, depicts a crimson sun, sinking into deep blue sea. A walk around Zurich is like a timeline of his life. ‘Love helps me find the colour,’ said Chagall. ‘I only have to apply it to the canvas.’ The shimmering colours of his canvases light up this smart but sombre city. And they will light up Liverpool too, when this illuminating survey of his early work transfers to the Tate in June.

Comments