On his deathbed in Dublin in the spring of 1966, Flann O’Brien must have been squiffy from tots of Paddy. A bottle of the amber distillate was smuggled in to the hospital on April Fool’s Day by a couple of well-wishers. O’Brien rang the bell to summon a nurse. ‘Sister,’ he told her solemnly, ‘I have two friends who are constipated and need a dose. Would you bring two glasses?’ Within a matter of hours the poker-faced Count O’Blather (O’Brien’s preferred authorial pseudonym) was dead. Flanneurs everywhere had reason to lament the passing of a notable Dublin wit and a writer of comic genius. But all was not lost. O’Brien’s masterpiece, The Third Policeman, was published the following year, in 1967; a novel from the grave, begob.

Flann O’Brien (real name, Brian O’Nolan) was born in 1911 as one of 12 children. His death at the age of 54 was from alcoholic complications and for much of his brief life he was indeed rotten fluthery-eyed drunk on Bass No. 1 Barley Wine, a beverage of near poteen-like potency. The literary funny-man act was of course inseparable from drink; O’Brien was at his satiric best in his ‘Cruiskeen Lawn’ column for the Irish Times. Written in 1940–66 under the pseudonym Myles na Gopaleen (Miles of the Little Horses), the column introduced readers to the archetypal Dublin man ‘the Brother’, whose homespun Paddy-boosted philosophy serves as a balm to pretty well every problem except alcoholism.

Beneath the Brother’s compulsive talkativeness one may detect the blarney and brogue of O’Brien the Dublin bar-room virtuoso. Not that he was a froth-blower of Brendan Behan proportions. As a respectable civil servant he could hardly turn up to work reeking of the Cork nectar. By 1953, however, his office-hour drinking had become such a problem that he was forcibly ‘retired’. (‘You were seen coming out of the Scotch House at 2.30 p.m.’, his superiors challenged him, to which O’Brien replied tartly: ‘You mean I was seen coming in.’)

At Swim-Two-Birds, O’Brien’s crazy spoof of Irish culture and folklore, was published in 1939 on the recommendation of Graham Greene, who was then a reader at Longman’s. The novel is structured around the now familiar modernist chestnut of a novel about a man writing a novel (about men writing a novel), but O’Brien’s was no mere exercise in self-reflexive preening. S.J. Perleman claimed him as ‘the best comic writer I can think of’; Greene compared him to the Joyce of Ulysses.

O’Brien’s work is, however, much more genial than Joyce’s; if anything, it speaks of a grave-faced eejit genius. A private individual, O’Brien chose to adopt a multitude of pseudonyms as a protective mask. Several of his aliases are on display in The Short Fiction of Flann O’Brien. Drawn from Irish newspapers and magazines, the short stories are not surprisingly full of beerswillers and liquorslobbers of one stripe or another. Sir Sefton Fleetwood-Crawshaye, OBE, the hiccup-shaken subject of ‘Donabate’, will go to any God’s length to satisfy his craving for whiskey. The story would be humorous enough were it not so pathetic.

‘The Arrival and Departure of John Bull’, a bravura performance, dilates wittily on Ireland, Irishry and everything Irish in general. W.B.Yeats had earlier been lampooned by O’Brien as the floppy-fringed Lionel Prune of the Celtic Twilight. Missing are his Damon Runyonesque whodunits written under the pen-name of Stephen Blakesley. Perhaps they never existed? (Answers on a damp stressed envelope, please, as the Brother might have said.)

O’Brien’s best-known play, Faustus Kelly, performed in Dublin in 1948, is a satire on the political wrangling and backstairs jobbery he knew so well from the civil service department of Dublin roads and drains. It is the highlight of Plays and Teleplays (a companion volume to The Short Fiction). Another theatrical curiosity, Thirst, tells of a publican nabbed by the police for serving alcohol after hours. The play was the 1942 Christmas production for the Dublin Gate Theatre and is still, after all these years, witheringly funny.

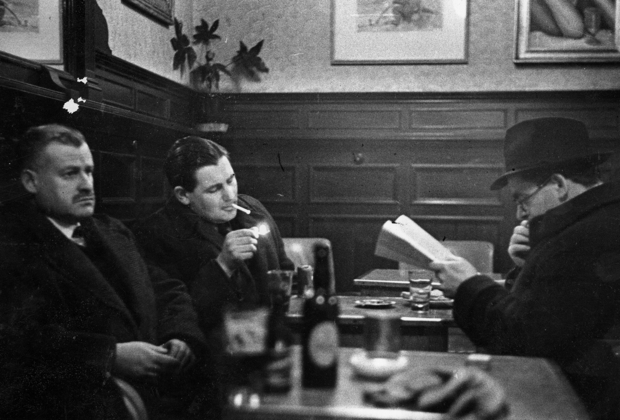

O’Brien was perhaps less suited to television production. His work for Irish RTÉ includes an off-puttingly gruesome comedy, The Dead Spit of Kelly, about a taxidermist who inhabits the flayed skin of his boss in order to appropriate his identity. Not included is the famous photograph of O’Brien standing in an overcoat and trilby hat next to a Dublin road-works sign: DUBLIN DIVERSION. The funny man of Hibernian letters lives on.

Comments