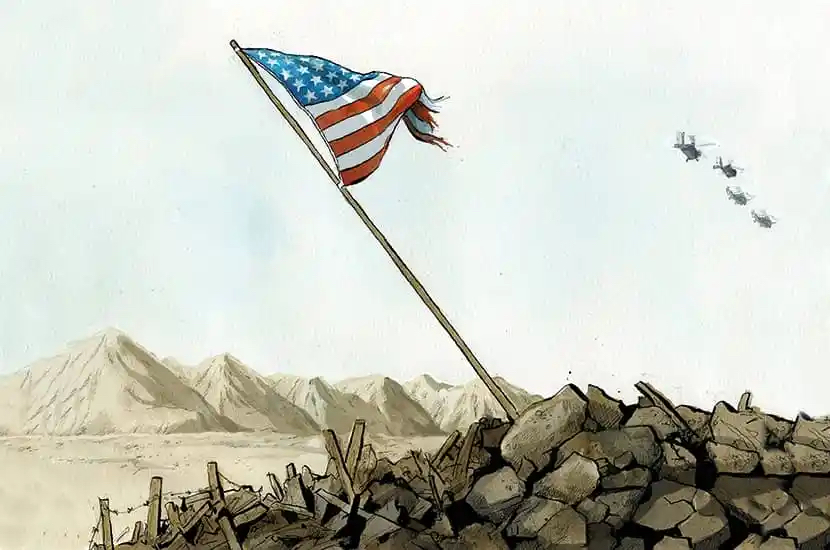

Back in March there was a glut of pieces about the 2003 Iraq war. The 20th anniversary seemed to much of the political and pundit class to be the perfect time to return to this scorched landscape. A number of people asked me to throw in my views and I failed, for two reasons. Firstly because, as some readers will know, I hate anniversaries and the lazy hook they provide to the news cycle. Secondly, because each time I sat down to try to write about those days I found myself unusually conflicted.

Those of us who defended the war have spent 20 years filled with ‘if onlys’

The reason partly relates to the wonderful, heroic former Labour MP Ann Clwyd, who died last week at the age of 86. After the war’s height, as the insurgency had begun, I went to Iraq with Ann. By then she already had a long and respected history of advocacy for the Iraqi people, and particularly the Kurds. This had come from visits from the 1980s onwards, when she saw for herself the terrible plight of the people whom Saddam Hussein had attempted to ethnically cleanse in the Anfal campaign and afterwards, through gassing, bombing and more. When Ann contributed to the parliamentary debate on the second Iraq war, the House was silent. Amid all the talk of WMD and more, here was a committed campaigner who could tell people first-hand the horrors of Saddam’s regime. It was a case I was in agreement with and to my great good fortune we became friendly.

Today there are no minds to change on Iraq. Those who opposed the war understandably point to the disaster that unfolded. Those of us who defended the war (many more at the time) have spent 20 years filled with ‘if onlys’ and agonised attempts to work out where it all went wrong.

Since Ann’s defence of the war was on principle, she did not waver. Tony Blair appointed her as special envoy on human rights in Iraq and on her visits she would dig into new problems as well as historic ones. She was welcomed by Kurdish officials like a queen. Their respect for her was incalculable. But she did not rest.

We spent part of our time inspecting Iraqi jails. These included some pretty hair-raising moments in cells packed with jihadists the authorities had picked up. In one Kurdish-run prison we met an Iraqi pilot whom the Kurds accused of involvement in the 1988 Anfal campaign. Ann wanted to be sure that the Kurds weren’t mistreating him.

It had been after seeing the Kurds fleeing across the mountains during that campaign that Ann’s interest in the Kurds grew. She was one of the formative figures in a group called CARDRI (the Committee against Repression and for Democratic Rights in Iraq). And while most of the world learned the name Abu Ghraib only in 2004, Ann was one of the few westerners who had known of the prison for decades, and knew what had gone on there while the Hussein family were in charge. I remember one torture cell we visited, from before the war, where a young Kurdish boy had carved into the wall ‘They are trying to change my age so they can kill me’. The unknown boy had obviously not been old enough for execution, so the authorities found their way around it.

There was plenty of such grimness. But Ann was an undaunted, positive presence. One day we travelled for hours to Kirkuk to see an official for yet another briefing on the latest situation. Our small group were all exhausted, the heat was suffocating, and in the early afternoon I noticed Ann’s eyes start to close. None of us had had any sleep and the other person in our party tried, with me, to cover over. I did that thing of suddenly accentuating words, but the midday heat soon did for me too. There was at least one period where I fear all of us were asleep. I remember waking, mortified, realising that this poor official had been sitting behind his desk while these strange British men and women napped in front of him.

But the truth is Ann was truly unflagging as well as brave. Her own vision of a post-Saddam Iraq did not emerge, though it sometimes seemed close. There were plenty of ‘what ifs’. One day we visited a Kurdish centre in Erbil and in the hallway and all the way up the stairs were huge framed photos of their heroes. These included, though were not limited to, colossal framed photographs of Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle. By then none of these men were much loved at home, but this corner of Iraq was grateful. History is complex when you’re going through it.

My own inability to make a full mea culpa over the years comes in part from that trip – and one day in particular. We were crossing the long mountain pass to Sulaymaniyah, near the Iranian border. It happened to be the day of Nowruz, celebrated by the Kurds as their New Year. During the Saddam years the celebration of this festival had been violently stamped out. But this year the Kurds were free, and as we wound through the mountain passes people poured out from every building. Men and women emerged from mud houses dressed in a finery that would be hard to pull off with the best tailors and dry cleaners in Mayfair. This huge colourful human wave spent the morning driving or walking into the green mountains. Up there, families and whole villages were picnicking, and by every roadside and on every mountaintop these men and women in traditional Kurdish dress were dancing their traditional Kurdish dance. Ann and I got pulled in. I can see that wonderful broad smile now as we joined the happy, strangely shuffling line.

All that magical day I had the strangest feeling of déjà vu and couldn’t work out why. It only dawned on me later. It was the scene in Narnia after the defeat of the White Witch. The land – this bit of the land at least – had been unfrozen and spring had finally come back.

Nothing can wash out the disaster. But when people talk about Iraq they want a ‘yes’ or ‘no’. To me it seems, at the very least, to deserve an ‘and also’.

Comments