I wonder how long it will be before we actually crawl back into the womb? The average mental age of our population stands at about four. A decade or so back it was surely higher — maybe six or seven, I would guess. But we have regressed with great rapidity, as if we were characters in a Philip K. Dick short story, hurtling backwards towards zero. One day soon we will have a national nappy shortage.

My wife made me watch part of a programme called The X Factor last Sunday. She said she wanted to watch this egregious shit because she was ‘tired’ and ‘there’s nothing else on’. I’m 90 per cent certain there was football on some channel somewhere, but I didn’t press the point. Anyway, the bit I saw was a ‘sing-off’ between two morons who were both incapable of singing and possessed of not even the remotest vestiges of talent. After they’d screeched their way through a couple of vacuous ballads they stood on stage hugging one another, like frightened toddlers at a pre-school nativity play. The audience — presumably adults, nominally at least — shrieked and howled like young children used to do in the Crackerjack audience. The hysteria was so overwhelming I wondered for a moment if they were all mentally ill. I assume they are the sort of people who go to places like Disneyland — without the kids. Adults are the big market for theme parks these days, not children.

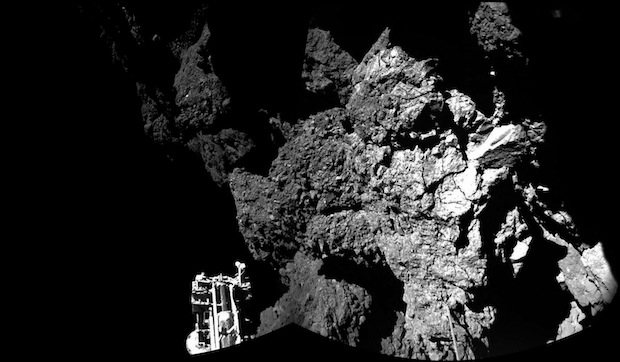

You might be saying to yourself — sure, the untermensch have the minds of three-year-olds. They have never been noted for their maturity, or their love of highbrow culture. That’s why they’re untermensch rather than ubermensch. But, oh, the disease is spreading — moving upwards into the sorts of places which used to be the preserve of real adults. Take the exciting news about the European Space Agency’s Philae probe landing on comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko — an achievement, to be sure. Something went wrong after touchdown and we were told that Philae consequently ‘tweeted’ the following: ‘I’m feeling a bit tired, did you get all my data? I might take a nap…’. I think if you were a pre-school teacher trying to explain what had happened to a class of not terribly bright three-year-olds, you could just about get away with that sort of anthropomorphism. But for the rest of us?

And then there was the shirt. The bad shirt. One of the leading scientists behind the mission, a heavily tattooed chap called Dr Matthew Taylor — who holds a PhD from Imperial College — was spotted wearing a colourful bowling shirt festooned with the images of scantily clad women. At this point the Twittersphere went berserk with fury — how dare he! Sexist pig! An insult to all women engaged in science and also to all women who are not engaged in science but undoubtedly would be if it weren’t for sexism like that. And also all other women every-where; spindle-thin Ethiopian women with high cheekbones and buckets of laundry on their heads, copiously swaddled Inuit fisher-women redolent of whale blubber, female Finnish social workers, female Romanian sex workers. All women, all terribly transgressed by that shirt. Which was also an insult to progressive men, of course, like myself. ‘Reprimand and apology in order!’ tweeted some pompous halfwit called Matthew Smith. Reading this irrelevant balls, it was impossible to escape the classic image of the toddler tantrum — such as the one exhibited by my daughter when she was two and a half, writhing on the floor of a Konditorei in Austria screaming: ‘I WANT NICE CAKE!’

And of course Dr Taylor was hauled to the front of the class and made to apologise. And what else did he do, as he grovelled? He cried. He broke down in tears, the poor sap. And so at a time when we should have been celebrating the most adult and complex and serious and magnificent of human achievements, we were presented instead with a cornucopia of modern infantilism: the tweet, the anthropomorphism, the tattoos, the silly shirt, the liberal-left tantrums, the emotional incontinence. And of all of these the tattoos are the most — what’s the modern word — iconic, the most obviously and conspicuously infantile. ‘I wan’ nice picture on my skin NOW daddy!’

Riding in a minicab the other evening I heard a 15-minute discussion between several adults on the radio about a fictitious penguin, and how utterly lovely he was, how incredibly moving. The debate related to a Christmas television advert for the John Lewis department store, a short film which concerned a small boy and a stuffed penguin. At least three of the people taking part in this sickly eulogising confessed to having cried when they saw it. Yes, they cried at an advert. What would they not cry at, then? If you can be moved to tears by shallow, twee, confected pap like that?

The first world war, I suppose. That would probably leave them dry-eyed. Another big business — Sainsbury’s — has decided that the first world war is a suitable subject for its Christmas advert, the thing which will convince people to buy Sainsbury’s brussels sprouts, Sainsbury’s brandy butter, Sainsbury’s self-basting turkey crown and Sainsbury’s deep-frozen breaded prawn canapés with Thai dipping sauce. The film in question focuses on the famous Christmas Day armistice in which British and German soldiers climbed out of their trenches and sang carols and played football. Hell, you know the story. All the soldiers in the film were healthy, unmaimed, incredibly good-looking, very clean. It is a view of the first world war — ‘evil thing war, and all the people who fight in wars are the same underneath and really love everyone’ — that you might present to a stupid three-year-old. I was tempted to turn up to my local Sainsbury’s and spray the aisles with mud, bayonet a few checkout babes and gas the shoppers with Yperite. But I suppose that would be an infantile response.

Comments