When the whole opioid crisis blew up, the Sackler family — whose fortune was substantially built on getting thousands of Americans debilitatingly addicted to OxyContin — withdrew for a period from their charitable giving. It was reported yesterday, though, that they’re back in the philanthropy business, and last year gave £3.5 million to various British causes — among them the Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra, the Watermill Theatre, King’s College, London, the homelessness charity Amber Foundation, various churches, academies and conservation projects. ‘The return of the Sacklers to philanthropy in the UK,’ the report stated confidently, ‘will cause outrage’. Really?

I remember being similarly perplexed when green campaigners were protesting about the National Portrait Gallery being sponsored by BP. It was outrageous, they said, that this vile fossil fuel company should be allowed to give away its money to a British art gallery. The artist Gary Hume said that the need for arts funding was ‘outweighed by the need to act urgently on the climate crisis’. That was a point of view, I suppose — and his argument that the gallery accepting the donations helped to ‘launder the oil industry’s image’ had something to it. But it seemed a nose-to-spite-face position to take.

That seems to me to be a sort of moral narcissism: insisting that if the people we hold to be baddies want to do something good, we need to thwart rather than encourage them

Look at this, perhaps, the other way round. Let’s say you have a company that has made zillions of dirty dollars polluting the sea, exploiting the nimble fingers of eight-year-old seamstresses in third-world sweatshops, or flogging fragmentation bombs to repressive regimes. What if some enlightened government decided to punish that company for its wrongdoing? How might it go about it? What would really show them? An obvious thing to do would be to confiscate some of its profits. And that money having been confiscated, what would the government do with it? It could, I suggest, donate the money to good causes such as galleries, theatres, schools, wildlife conservation and what have you.

Would right-on people, in such a circumstance, be tut-tutting at the arrangement? Would they be insisting that the money be forgone by these good causes and returned to the offending multinational and its unscrupulous shareholders forthwith? I would have thought, rather, that they would clamour for ever greater confiscations, ever greater donations to good causes. Yet what we have at present — the arrangement that is held to be unseemly — is exactly the same result achieved by different means. One way or another, the wages of sin are being redirected into causes of which most or all of us can approve.

Is the thing that sticks in the craw, then, that the Sackler family has the audacity to hand over some of their ill-gotten gains voluntarily? This principle, if you could call it that, seems to hold that the results be damned — it’s the means that matter. That seems to me to be a sort of moral narcissism: insisting that if the people we hold to be baddies want to do something good, we need to thwart rather than encourage them so as not to be seen to in any way give succour to the enemy. We want their badness to remain uncompromised, uncomplicated; the better to burnish the contrast with our own virtue.

That, I humbly submit, is just silly. There’s a wisp of an argument that says that such donations are a tax efficiency of one sort or another; and another wisp of an argument that says that it’s distasteful that companies not deserving of respect should be allowed to plaster their names in places of honour above wings of galleries.

But they are just wisps of arguments. Of course we can, and perhaps should, tinker with the tax breaks — but on the whole, there’s a good case for being thankful that at least some of such a company’s profits end up paying for something worthwhile, rather than sheltering behind a brass plaque in Belize. Philanthropy is only one of the tax avoidance schemes available to multi-million-pound companies, and it’s probably the one that does the greatest public good.

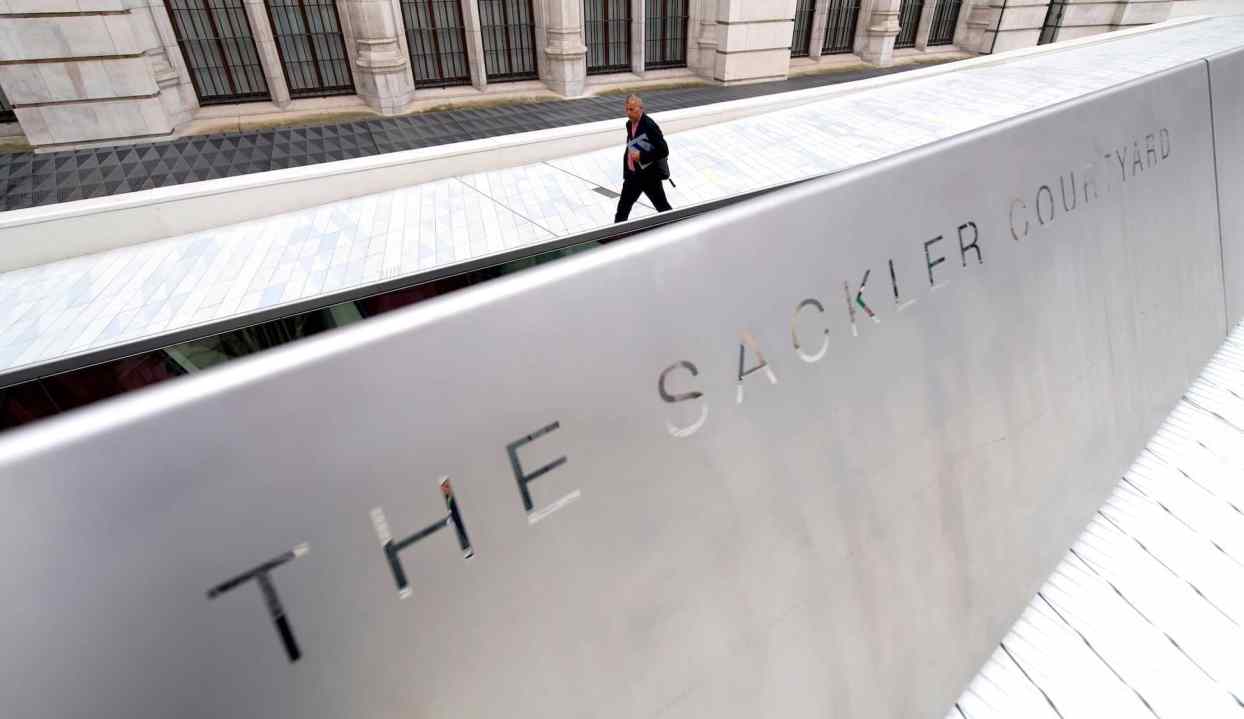

And, sure, it’s for the institutions themselves to decide whether ‘The Sackler Courtyard’ or ‘The Sackler Institution’ or ‘The BP Portrait Prize’ is the sort of branding that they’re prepared to wear in exchange for however many millions they would not otherwise have had. But it’s possible to overstate how much a name on a plaque really does to launder a company’s image. Indeed, inasmuch as they bring anonymous companies into the light of day, that sort of branding works against them as much as it works for them. Who outside the City had heard of the Man Group (blameless folk, I should say — I used them as an example) before they sponsored the Booker Prize? Were BP’s yellow-and-green logo not affixed to the National Portrait Gallery, there’d have been nothing for eco-graffiti to deface, nor the occasion to write hostile articles about their sponsorship in the press.

Anyone who cares to know who the Sacklers are and how they made their money can find out with a 30-second Google search. And the money itself isn’t magical: the sin that made it is not contagious. Arts, education, conservation — all of these things need all the help they can get. And the sorts of companies or families that are in a position to help seldom make that sort of money without getting it in ways that don’t bear very close examination. These schools, galleries and orchestras should hold their noses, rattle their piggy banks, and take the dirty dough with good grace.

Comments