Whose were those feet in ancient time that walked upon England’s mountains green? That William Blake assumed his readers were on his same wavelength is one of the things, according to John Higgs, ‘that makes his writing a glorious puzzle’. Equally puzzling, argues Higgs, is that the cockney visionary, unsung in his lifetime and buried in a pauper’s grave, has now been absorbed thoroughly into mainstream culture without our having the faintest idea of what he was on about.

Take the 20th-century adoption of ‘Jerusalem’ as England’s alternative national anthem: in its original context as the preface to Blake’s long poem ‘Milton’, the hymn that marks the end of our school terms and party political conferences was intended to describe the overthrow of these very institutions. There is a similar irony, says Higgs, in placing Eduardo Paolozzi’s bronze Newton in the forecourt of the British Library: the object of the Blake print on which the statue is based, ‘Newton: Personification of Man Limited by Reason’, was precisely to challenge the limitations of book-based learning.

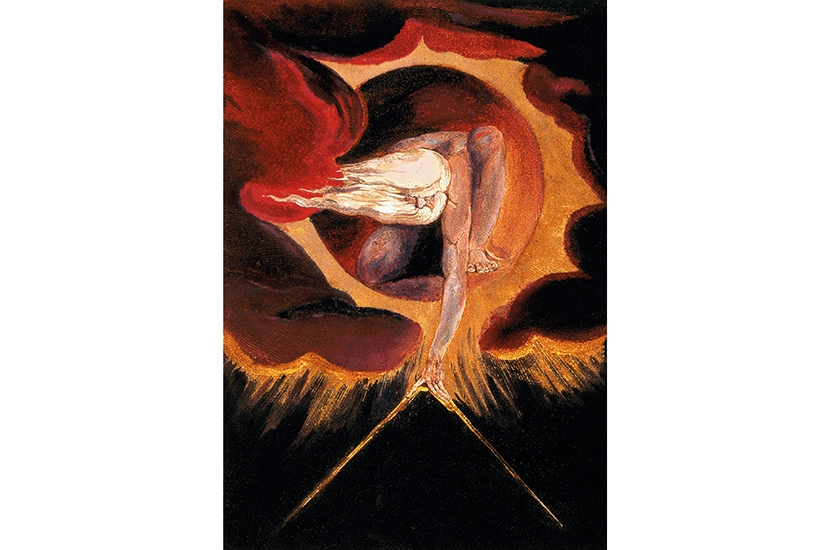

The finest of all our misreadings of Blake, however, was when on 28 November 2019 ‘The Ancient of Days’ was projected onto the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral. Here, squatting naked above the great church with his long hair and white beard blowing in the wind, was Urizen (‘your reason’), marking out with his golden compass the soulless world in which we live. He might look like God but Urizen was, in Blake’s mythology, Satan himself. Higgs explains:

No one has ever understood everything that Blake wrote, possibly including Blake himself. But as Obi-Wan Kenobi asks rhetorically in Star Wars: ‘Who’s the more foolish — the fool, or the fool that follows him?’

In William Blake vs the World, Higgs makes a laudable attempt to explain Blake to the nation and then, to paraphrase Byron, to explain his explanation. What did Blake mean, for example, by the proverb ‘Without contraries is no progression’, or by his belief that while God created man, man also created God? And how should we interpret his casual accounts of conversing with angels, whether on Peckham Rye, where his earliest vision took place, or otherwise? ‘I have always found,’ said Blake, ‘that angels have the vanity to speak of themselves as the only wise.’ Was Blake an artist, a genius, a mystic or a madman, wondered Henry Crabb Robinson, after spending an evening with the elderly poet. He was all of those things, says Higgs, except the last. ‘As the late maverick Ken Campbell used to insist, “I’m not mad, I’ve just read different books”.’

Apart from the Bible, Blake’s great influence was the Swedish theologian Emanuel Swedenborg, whose book Heaven and Hell was satirised by Blake in ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’. Starting out as Swedenborg’s student, he ended up as his nemesis, but then ‘opposition is true friendship’. The most engaging of Blake’s oppositions can be found in the contrast between the immateriality of his thought and the ‘infernal’ labour involved in getting his ideas circulated. Blake illustrated, engraved and printed his books himself. This involved not only scratching thousands of lines, dots and crosses onto sheets of copper, but using mirror writing, so the finished text would not read backwards. Higgs compares his one-man publishing industry to ‘the do-it-yourself ethos of punk rock’.

At the heart of Blake’s world was the power of imagination, which faculty he believed would free us from our mind-forged manacles. Imagination, represented in Blakean mythology by Los, is the opposite of the reason, and we cannot understand Blake without understanding what he meant by imagination or taking seriously his visions. Higgs does this admirably, by exploring what we know about the mind while maintaining, for our secular times, the sacred quality of Blake’s attention. For Blake, the dividing line between the external and the internal was porous, and his capacity to see more than the rest of us might be explained by his having hyperphantasia. The mind’s eye of those with hyperphantasia is morevivid — both visually and in every other sense — than it is for the rest of us. ‘To a hyperphantasic,’ Higgs argues, ‘images are not things that you think, they are things that you encounter.’

Higgs compares Blake to the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu; also to Leonard Cohen, David Bowie and Lennon and McCartney: ‘To judge Blake by Songs of Innocence is like judging the Beatles by the song “Yellow Submarine”.’I grew weary of these analogies — further misreadings, perhaps, which do little to explain Blake’s sublime strangeness; but then this book is not written for my generation. William Blake vs the World is a primer for the future. Witness the statement: ‘Blake appears to have been cisgendered and heterosexual, but there may have been a transgender aspect to his sense of self.’ It might be one of the Proverbs of Hell.

Comments