There’s sound thinking behind this summer’s resuscitation of London City Ballet – a medium-scale touring company popular in the 1980s that went bust in 1996. Given that larger institutions operating outside London such as Northern Ballet and Birmingham Royal Ballet are hamstrung by ever-tightening budgets that leave them increasingly risk-averse, there’s a crying need for something lighter on its feet and more adventurous in its repertory. This is what the new-form LCB under the direction of Christopher Marney sets out to provide, presenting new work alongside forays into the back catalogue.

If you aren’t thrilled by the finale of A Chorus Line, then there’s no hope for you

For LCB’s inaugural season, Marney has assembled a modest but sensible programme, well-rehearsed and crisply executed. It opens with a piece of tights-and-tutu froth conventionally choreographed by Ashley Page in 1993 to the Waltz from Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin. Quite why this anodyne piece was chosen is a mystery – there’s so much in a similar vein of more substance – but it’s pleasant enough.

What follows is more rewarding. Kenneth MacMillan’s Ballade hasn’t been seen since 1972 – and never in Britain. Three men are in subtle competition for one evasive woman. On a white set in everyday white costumes, the mood is superficially amicable, as friendly negotiations are conducted round a table. But something more emotionally complex emerges as the woman is aerially passed around in a sequence that echoes the second act of Manon.

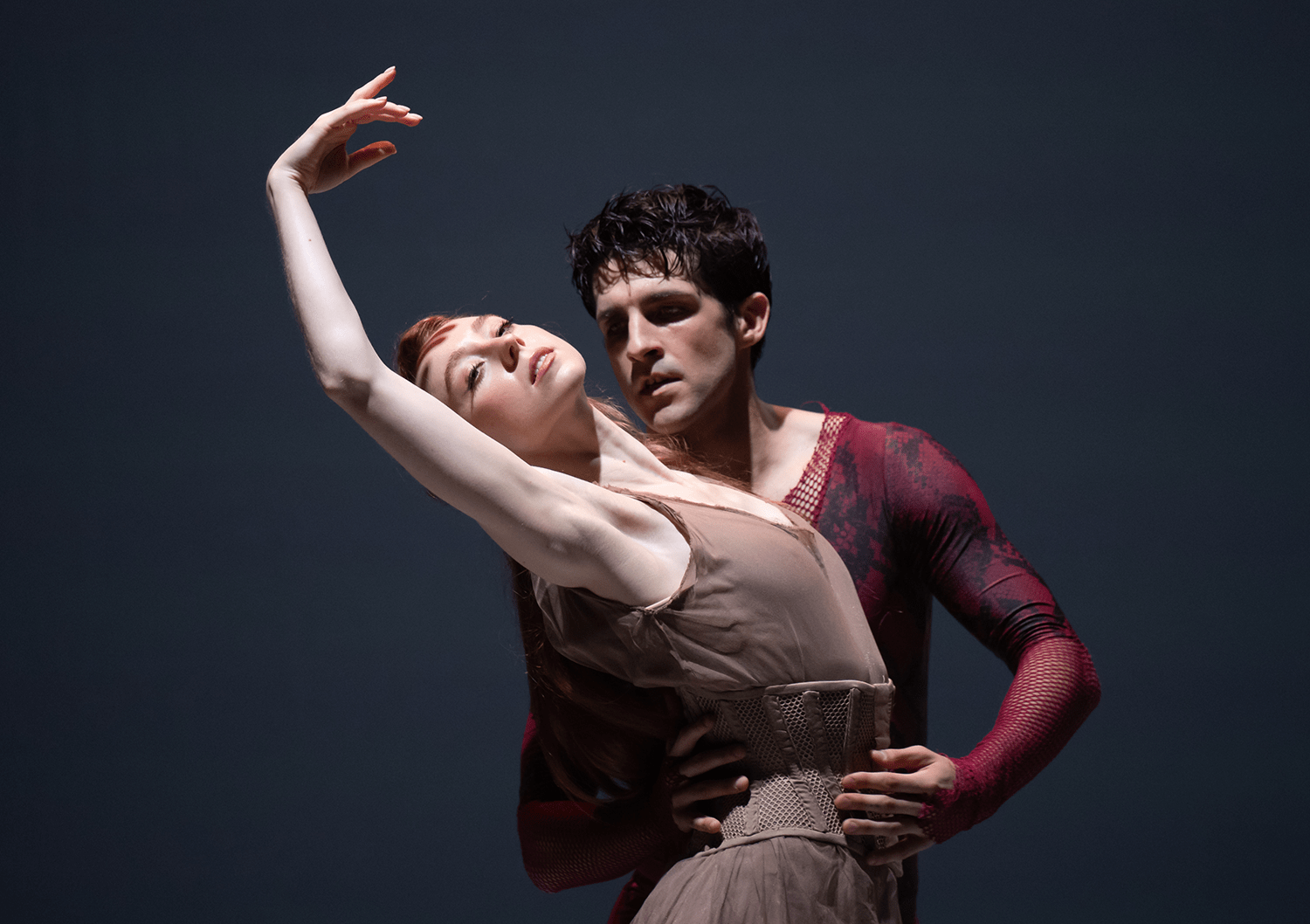

Arielle Smith’s Five Dances is the first of two new pieces: abstract in style but vigorously responsive to a score by John Adams, it’s performed with muscular energy. More arresting, however, is Marney’s Eve, an anti-pastoral set in a garden of Eden where a slitheringly attractive serpent graphically seduces a naive Eve, whose bite of the apple has spectacular consequences of an apparently positive kind.

Among an eclectic baker’s dozen of dancers, the darkly intense Spaniard Alvaro Madrigal stands out. Alina Cojocaru joins for a brief run at Sadler’s Wells next month, following a visit to China: her genius may raise the temperature further.

In its previous incarnation, LCB traded heavily on the patronage of Diana, Princess of Wales and perhaps it should now stop opportunistically leaning on that moribund association (pace the historic video footage projected between the items). The company must also find a more inspiring name for itself: we don’t need to be told that London is a city. In these straitened times I suppose we must accept canned music, but it doesn’t add to the glow. The offering could be more generous too – a second half lasting barely 20 minutes is short measure that punters will resent. But it’s a nice change to be left wanting more – and I hope to see LCB thrive.

A quick look at West End show-dancing. Last autumn’s Crazy for You with the fabulous Charlie Stemp (currently in Kiss Me, Kate at the Barbican) had the ideal zip, wit and elegance, but the genteel hoofing in this summer’s hit Hello, Dolly! won’t generate much excitement (though it’s worth seeing for the sublime Imelda Staunton). Now comes the return of one of the greatest of dance musicals, A Chorus Line, in a production which originated at the Curve, Leicester, that runs through this month at Sadler’s Wells.

Even though its score isn’t top notch, there’s a potent idea behind the drama: the brutal selectivity of the audition process, the subsuming of individualities into a greater whole embodied in the show’s strongest number, ‘One’ – a brilliantly constructed climax. I wish that Nikolai Foster’s efficient staging hadn’t made such clichéd use of live-film projections, and Adam Cooper may be too darn nice as the taskmaster director Zach. But Ellen Kane’s choreography, drawing on Michael Bennett’s original, has razzle-dazzle and a characterful cast of all shapes, sizes and colours attacks it with gusto and precision. If you aren’t thrilled by the finale, then there’s no hope for you.

Comments