In the early 1860s, the teetotal vicar Revd Henry Solly founded the very first working men’s clubs. Like so many middle-class radicals, he failed to understand the true appetites of the working classes. Where Solly had visions of ‘education’ and ‘wholesome recreation’, real working men had different ideas: they wanted booze.

Real clubland is not in St James’s. Instead, it can be found some 100 miles north

By the 1970s, there were over four million drinkers visiting 4,000 clubs across Britain. There was live entertainment, big pot parimutuel betting, and copious amounts of subsidised drink. Some had Sunday afternoon strippers. Then British industry came crashing down, the miners of Orgreave had their heads smashed in, and their jobs went abroad. Now, half of our coal is shipped over from the United States, and most of us work in offices.

With proper working men gone, there are only 1,100 clubs left, and more are closing every month. Yet there is still a place for the working men’s club (if not the Sunday afternoon strippers). In all my years of legal and extra-legal drinking, I have visited over 50 working men’s clubs and have worked in three. They are places of mischief and tradition. Take the club in Weardale, County Durham, where you’re served a pint of scrumpy topped up with a healthy dose of sherry. In Fife, the favoured drink is a ‘club measure’ (a triple shot) of O.V.D. rum, known among connoisseurs as ‘Dundee diesel’. Leek shows are a yearly event at the club in Tyneside, with prizes for the grower of the biggest vegetables. Some engage in the darker gardening arts, given the offer of a free fridge freezer, television, or oven. My grandfather once paid a friend to use one of his oversized homegrown leeks, so as to be in with a shot of winning some white goods.

Unlike the modern pub giants, clubs are not primarily interested in maximising profit for shareholders. It’s quite normal to see a sub-£3 pint in the clubs of the north of England. They are places for old men to socialise, keeping their minds and bodies active. I can say with some conviction that I have never stolen a pint glass from a working men’s club (whereas my student kitchen is filled with Greene King glasses).

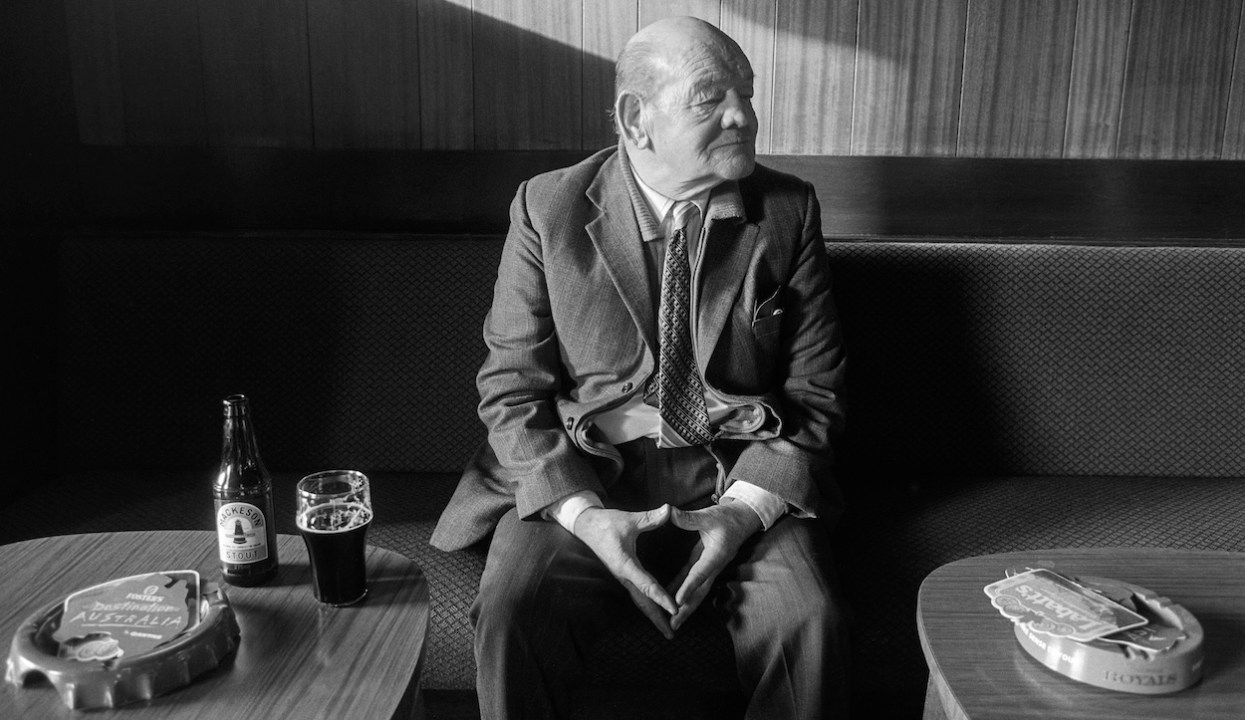

The traditional choice of seating is the banquette, often upholstered in House of Commons green or Lords red, but lacking the same plushness. Toilets tend to be on the grimmer side, though not uncomfortable. If you are an advocate of the old-school ceramic trough urinal, as I am, most clubs will meet your expectations. Rather than curtains, which supposedly provide warmth and texture to a room, clubs almost always opt for blinds. These come in one colour – nicotine yellow – a reminder of the pre-ban glory days. Unlike pubs, which have food and so-called ‘ambiance’, the club revolves around the singular force of the pint. The cheaper, the better.

Beyond the cold appeal of frugality, the other great element of a club is the strange regulars. You’ll find octogenarian domino sharks ready to relieve you of your beer money. A cousin of this breed control the snooker tables, gambling their hard-earned change on the frayed baize. These men represent the tragic side of club life – they are prodigious talents of the mundane.

The fruit machine merchants plummet even greater depths of pointlessness. There is no sadder sight than a grown man, on the last Friday of the month, feeding a fruity for hours at a time. Every half hour or so he’ll make the forlorn trip back to the bar to break yet another £20. He is the only one convinced that he has the computer beat; he is sure that with just a few nudges, offered with just the right amount of force and at just the right moment, he will win the jackpot. Barmen have been told of this occult wisdom thousands of times over, yet are still polite (or cunning?) enough to simply nod along. Revd Solly would no doubt have been appalled.

Club men are not all tragicomic; some are just plain funny. Take, for example, the Sunday clubber, a species sadly on the verge of extinction. As the man of the house, the Sunday clubber is duty-bound to leave home around 11 a.m., consume upwards of seven pints of Best, and return around twelve hours later to find his dinner burnt in the oven. He will likely return to the club at opening time on Monday – 6 p.m. or so – ready to make up for the missing daylight hours. Men who preserve this tradition are few and far between, but deserve credit for their dedication to the cause. Then there are the much-maligned committee men, a group of elected elites who deal with the day-to-day administration of the club: a thankless task, they receive little more than accusations of nepotism, corruption, and incompetence.

Finally, there are all those who defy categorisation: the disbarred lawyer, the one-time millionaire who lost it all on Black Wednesday, the company chairman on the take, the geriatric with faded prison tattoos, the gangsters, the plastic gangsters, and among them all, the regular, hardworking men just out for a drink. Real clubland is not in St James’s. Instead, it can be found some 100 miles north, up the M1, starting somewhere around Derby. You southern toffs can keep your Garricks and your Reforms – the proper British club serves Boddingtons, not Bollinger, and you’d be laughed at if you turned up in loafers.

Comments