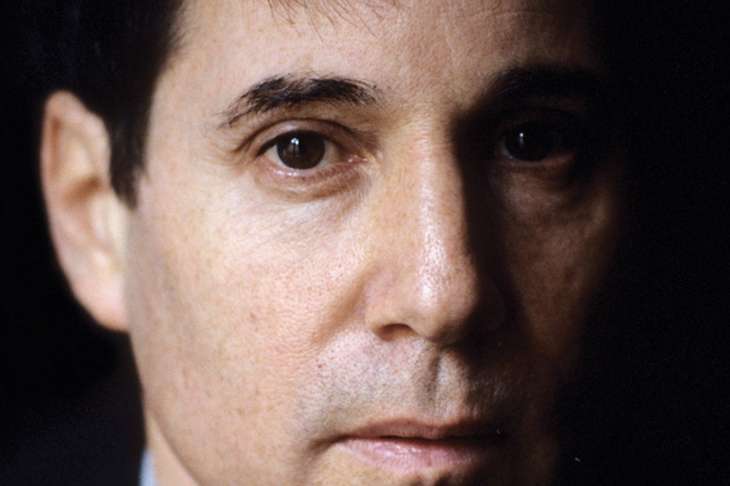

Someone has gone to a lot of trouble choosing the jacket cover of Robert Hilburn’s authorised biography of Paul Simon (reproduced right). It is both flattering and enigmatic, which is entirely appropriate, given its contents. Half of Simon’s features are lost in a shadow cast across his face — again, entirely appropriate, as Simon wrestled with Hilburn for more than two years, determined to ensure his true self remain partly or wholly in the shadows.

One can’t help wondering why thesinger-songwriter even agreed to sit for what the jacket copy assures us was 100 hours of interviews; or, indeed, what happened to the other 99. For Simon’s voice barely rises above a whisper in a book apparently designed to counteract the impertinently unauthorised portrait painted by Peter Ames Carlin in his workmanlike Homeward Bound, published in 2016.

Hilburn — the Los Angeles Times’s chief pop critic for more than 30 years — has been obliged to write a biography of a 60-year career with one hand tied behind his back. The biographer’s job is to delve and to pry, to lift lids living artists would prefer stayed battened down. When Bob Dylan told a mutual friend he found my biography of him ‘too personal, too probing’, I couldn’t have been prouder. So when I heard that Hilburn, a writer I greatly admire and the author of a fine biography of Johnny Cash, was tackling the prickly Mr Simon, I was intrigued.

As with any deal with the devil, the devil is in the detail. As one of those annoying people who read the acknowledgments first, I immediately noted a gaping chasm: no Art Garfunkel. Given that Art needs money, it’s no great surprise that he was threatening to write his own memoir (and did), so would not talk. However, Simon’s rocky relationship with his old friend has been rigorously explored in numerous interviews with Art over the years (sometimes in the face of self-interest, as Simon dangled a possible reunion tour in his face). And Carlin did the spadework necessary to compare and contrast Art’s ever-changing views.

But Hilburn largely confines himself to the ‘Simon Says’ version of events regarding Art, acting at times more like a ghostwriter than a biographer. Paul the put-upon also seems to have succeeded in cowing his first and third wives — only the first of whom Hilburn got to interview — into avoiding some thorny questions.

Thus, we are asked to believe that the relationship between Simon and his manager’s ex-wife, Peggy Harper, did not bloom until her marriage broke up, even though Hilburn reports that she flew directly from a quickie Mexican divorce to Monterey to see Simon and Garfunkel play at the legendary 1967 pop festival. Are we meant to believe that seeing Paul was the last thing on her mind?

As for a widely reported incident of domestic violence in April 2015 involving Simon and his current wife, the singer Edie Brickell, Simon simply declined to discuss it with Hilburn.

Indeed, asked to explain any controversy in his life — his appropriation of Martin Carthy’s arrangement for the million-selling ‘Scarborough Fair’: the non-credit for Los Lobos’s part in Graceland’s ‘Myth of Fingerprints’; re-recording an entire Simon and Garfunkel reunion project as a solo Paul Simon album (Hearts and Bones) — Simon is as slippery as an eel and as self-justifying as an O.J. Simpson juror. What comes across is one seriously po-faced, self-important artist. Despite constant references to his enduring friendship with Lorne Michaels, the creator of Saturday Night Live, there is not the slightest evidence of Simon cracking a smile or a joke throughout his interviews with Hilburn.

I can’t say I’m surprised. My favourite Paul Simon story, told by his London flatmate Al Stewart, shows a man with a real chip on his shoulder. It involves him returning unexpectedly one afternoon in 1965 to find Al playing Dylan’s ‘Desolation Row’, from the recently released Highway 61 Revisited. Simon begins to berate Stewart for listening to all these ‘half-baked Ferlinghetti lines’, at which point Stewart informs him he will never write a song this good if he lives to be 1,000. Simon storms out and does not return for two days. We’re still waiting, Paul.

And yet, there is so much to admire in Simon’s work. The way he transcended the sophomore sensibilities of Simon and Garfunkel with those first three solo albums, including the still-unsurpassed There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, is dealt with judiciously by Hilburn, as is the pressure Paul felt trying to escape S and G’s shadow.

Hilburn also ably demonstrates the respect in which Simon is held by fellow songwriters, even as the critics continue to relegate him below Laurel Canyon’s ladies and gentlemen. He even seems to share Simon’s delight in winning all those Grammies, though his decision to reproduce some of Simon’s best-known lyrics is unlikely to convince the Swedes to award him a Nobel Prize for Literature any time soon. Thankfully, a rock feels no pain.

Comments