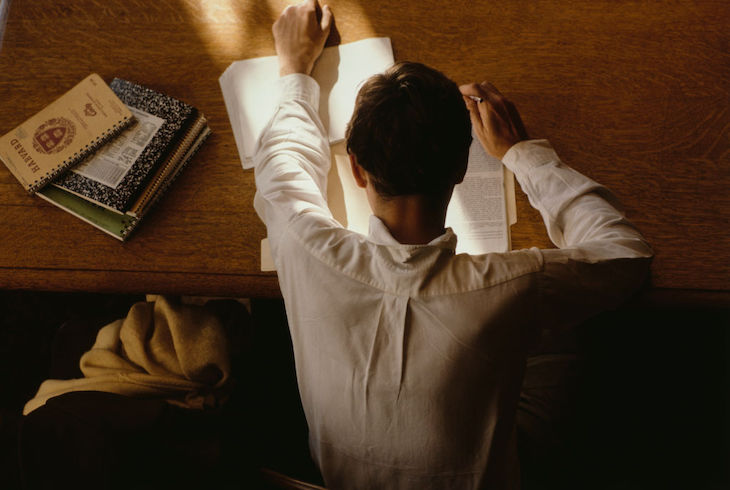

The question has changed, as one Oxford don noted wanly on social media, from ‘What are you reading at university?’ to ‘Are you reading at university?’ Such is the state of undergraduates entering English Literature courses these days, brains addled by scrolling on their mobile phones, that universities are now offering ‘reading resilience’ courses to help them tackle the unfamiliar task of reading long, old, sometimes difficult books.

It’s a whole new cause of gloom to discover that even students who have actively signed up to study English Literature at university are struggling to read books

We’re accustomed, some of us, to feeling gloomy about the sinking popularity of Eng Lit – once comfortably among the most popular choices at A-Level and most applied-for at university; now very much not. We’re accustomed, too, to regretting the gobbetisation of how it is now taught at GCSE and A-level, and the drive to teach ever shorter texts in the face of dwindling teen concentration spans. But it’s a whole new cause of gloom to discover that even those students who have actively signed up to study English Literature at university are struggling to read books.

There are arguments to be had, heaven knows, about the value and purpose of English Literature as an academic discipline. They have been being had since it first came into being. Did acquaintance with the great works, as F R Leavis (and before him George Eliot and many others) thought, improve you morally? Or, when that line started to seem a bit airy-fairy, was formal analysis – structural morphology, and all that jazz – the respectable way to go?

When literary theory swept through the academy in the 1980s and 90s, you could see dons latching onto it with a yelp of relief, as if to say: we’re doing something intellectually rigorous now, not just reading stories and poems and responding to them. Marxist and feminist critics corralled the literary canon into a branch of the social sciences; the deconstructionist mob tried to yank it into philosophy.

And the economic utility of it – as if that’s the point – has always been questioned. When I was an Eng Lit undergraduate, the standard joke was: ‘What do you say when you meet someone with a PhD in English? Big Mac and large fries please.’ That joke, alas, has now become the organising principle for successive metrics-minded governments to sideline the arts in favour of STEM.

But wherever the world may stand on the value of an English Literature degree, if you’re signed up to one as an undergraduate, you’re presumably on board with thinking there’s a point to it. And that means reading books. Often very long ones. Sometimes difficult ones. It is the entire point of reading English Literature. You don’t join a paratroop regiment and then decide that, on subsequent consideration, you’re not wild about the idea of jumping out of planes.

Eng Lit, in this respect, is something of a bellwether. If we lose our ability to read books – properly read them, all the way through – we are cooked as a civilisation. Books are what made that civilisation in the first place. They are the best means yet devised of transmitting deep thinking and rich bodies of knowledge across generations. The internet is not a substitute. Memes are not a substitute. TikTok videos are not a substitute. Tweets, fun though they may be to send, are not a substitute. And generative AI – that Dunning-Kruger regurgitation machine entirely built on the theft of those texts whose readerships it is destroying – is certainly no substitute.

It seems to me that most of the ills that plague our public discourse – the polarisation, the binary thinking, the historical illiteracy, the narcissism, the privileging of emotion over reason where the only emotion to be considered is your own, the astounding impunity towards outright lies – are ills to which the main corrective is reading books. Only in reading books do you discover that this issue or that is more complicated than you thought, that propositions of the both-and type rather than the either-or exist, and that there are truths that it is not possible to express in a spicy tweet. Books, because (with a few admitted exceptions, such as On The Road) they are the considered and painstaking work of many solitary hours and much revision, supply the antidote to the hot take, the angry riposte and the overconfident assertion. They are the slow-food movement of the intellectual world.

I’d go further, too. To return to the original topic of English Literature as a subject, I think that fiction and poetry have an incomparable value. Novels are empathy machines. They ask us (in an age when the dominant cultural impulse is to demand the admiration of others) to imagine what it might be like to be somebody else. Failure of the imagination is a species of moral failure; perhaps the worst. The first step on the road to atrocity is the inability to see your enemies as fully human. Cockroaches. Zionists. Orcs. Mussies.

‘Reading resilience’? Reading is what gives us resilience. Read some damn books, kids, or we’re all doomed.

Comments