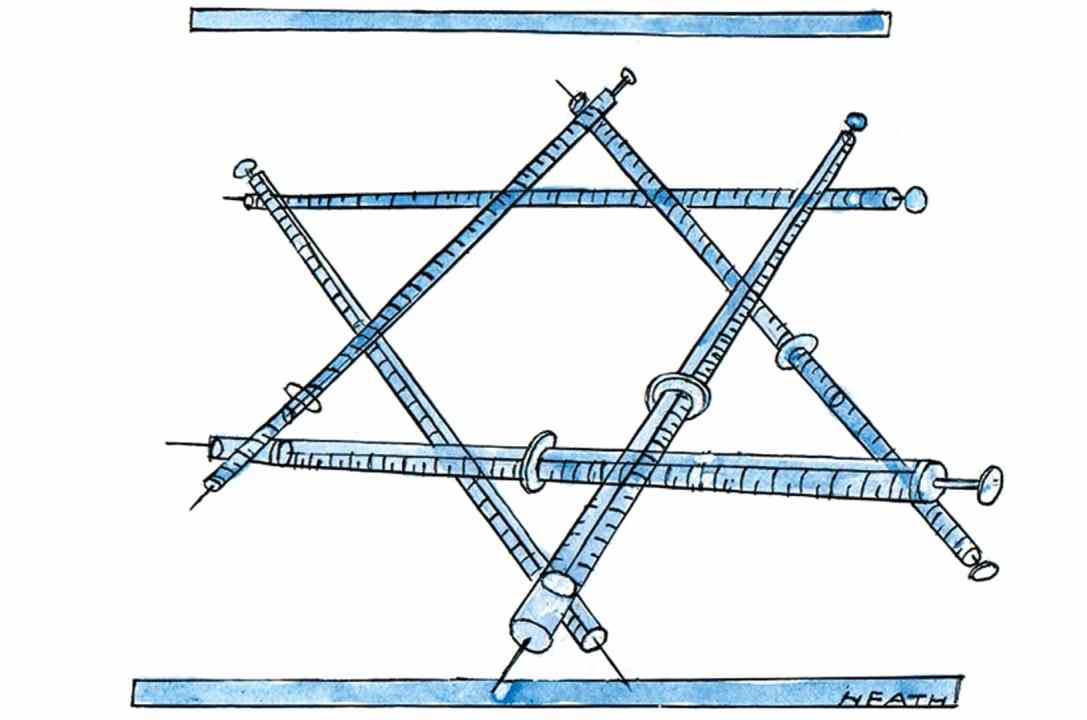

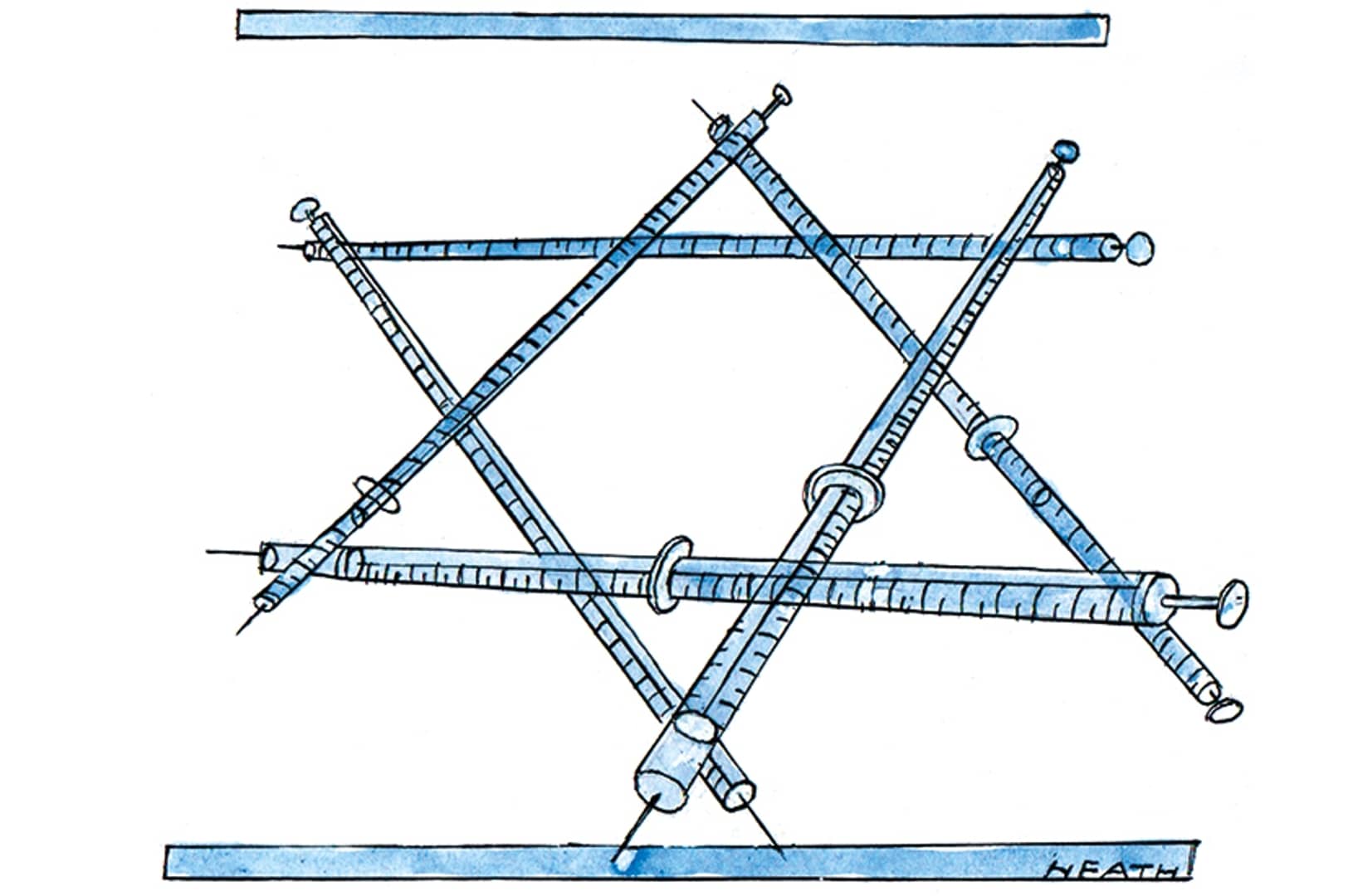

Boris Johnson’s announcement about vaccine passports was met with criticism from backbenchers on both sides of the political spectrum. The scheme was described as potentially ‘discriminatory’ with warnings that it may lead to a ‘two-tier’ Britain. Labour leader Keir Starmer even said the use of vaccine passports is ‘not British.’

Given the deep suspicion towards national identification cards, this did not come a surprise. But if the government eventually chooses to use vaccine passports, some lessons from Israel’s experience may be helpful.

Despite their cultural differences, the Israeli and British publics are protective of their democratic rights and liberal freedoms

Israel has been giving digital certificates to people following their second vaccination or issuing ‘recovery certificates’ to those who have had Covid-19. The scheme started in February – only after every adult in the country had been offered a vaccine. To register for a passport online, Israelis need to give their ID or passport number, date of birth, and approval for their health care provider to verify the person has received the vaccine or recovered from Covid. The certificate is now a requirement for visiting a long list of public places, including gyms, restaurants (although only for sitting indoors), football stadiums, theatres, museums, conferences, shopping centres and other large venues. A vaccine certificate also provides freedom from quarantine and fewer restrictions during international travel.

There was little public debate about the use of certificates before the scheme started; most Israelis either supported it and viewed it as necessary in order to resume normal life, or had more passively resigned themselves to this new reality. The majority of Israeli Knesset members in parliament did not voice their opposition. The strongest criticism came from a small group of anti-vaxxers, some of whom see the virus as nothing more than a conspiracy. Others don’t deny the pandemic but are refusing a vaccine for other reasons. Some anti-vaxxers have gone so far as to call the certificates ‘oppressive,’ comparing them to the yellow badge that Jews were forced to wear during the Holocaust and to events in The Handmaid’s Tale.

The certificate comes in the form of a QR code. One major problem with the vaccine passports involves security risks; QR codes aren’t difficult to falsify, and as a result, a profitable industry of fake certificates soon emerged, some of which can be ordered on the encrypted messaging platform Telegram. Israeli cyber-security experts have raised the alarm with the Israeli Health Ministry and are urging it to replace the QR codes with other more secure and difficult to forge technologies. An alternative to QR codes are digital signatures with two mutually authenticating cryptographic, mathematically linked keys; a public key and a private key that encrypts data. The public key is shared with businesses and venues that need to access the certificate. The private key has to be kept secret on secure government servers, making faking the code much more complicated.

Over a month into the scheme, Israel is making it easier for foreign visitors to travel into Israel – if they have been vaccinated. Without proof of vaccination, any visitors will have restricted access to certain venues. Israel has also been negotiating with foreign governments about recognising Israeli vaccination certificates for those travelling abroad. Other countries, including Malta, Greece and Croatia, similarly announced that vaccinated tourists could avoid quarantine.

Notwithstanding the domestic objections to the use of vaccine passports in Britain, they may soon become a requirement for international travel for those who want to avoid taking multiple tests or spending time in quarantine. If the government chooses to adopt vaccine passports, it may be wise for it to negotiate international agreements in order to guarantee they are recognised by other countries. Even if the government chooses not to adopt passports, it should still offer proof of vaccination to those who want to have an internationally-recognised certificate to travel abroad.

Despite their cultural differences, the Israeli and British publics are quite similar and protective of their democratic rights and liberal freedoms. Therefore, if the reaction of Israelis is anything to go by, many people may not be overly bothered in Britain by the scheme if it helps keep transmission low.

Critics and proponents of the scheme agree that ethical issues should be considered and addressed. To avoid discrimination, the scheme should be applied only after all adults have been offered two jabs, as in Israel. But unlike the Israeli scheme, more thought needs to be given in how not to discriminate against anyone who cannot, for medical reasons or age, be vaccinated, while protecting them from contracting the virus in public places.

Comments