The centenary of August 1914 is still almost a year away, but the tsunami of first-world-war books has already begun. The government tells us that 1914 must be commemorated, not celebrated, and ministers worry about British triumphalism upsetting the Germans. But the debate about Germany’s responsibility for the outbreak of war in 1914 won’t go away. Historians are divided into those who blame Germany — John Rohl, Max Hastings — and those who point the finger at someone else, such as Serbia (Christopher Clarke) or Russia (Sean McMeekin) or even Britain (Niall Ferguson). The blame game is of course conceptually flawed. The international system in 1914 was seriously dysfunctional. The alternative to searching for scapegoats is to examine the system. Why was it that political solutions no longer worked, so that conflicts could only be resolved by war? That is the question at the heart of Margaret MacMillan’s important new study.

Beginning in 1900, MacMillan shows that it was the German navy more than anything that poisoned Britain’s friendship with Germany. Tirpitz, the minister responsible, intended his navy to force Britain into friendship, but it had the opposite effect — it drove the British to compete, and compelled them to find new allies. Here, as MacMillan suggests, the decisions of individuals — Tirpitz and the Kaiser, who backed him — really did change history. When first France made the entente with Britain in 1904, and then Russia chose Britain over Germany in 1907, Europe was divided into two camps.

This is a well-known story, and MacMillan tells it well, enlivening her narrative with character sketches. Schlieffen, the man who drafted the German war plan, was a grim, work-obsessed Junker who was always at his desk by 6 a.m. The Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph rose even earlier, hitting the paperwork at 4 a.m. Both of these workaholics left their jobs in a dreadful mess — the world might have been a better place if they had stayed in bed in the mornings. Winston Churchill too was an overzealous worker: his reforms as First Lord of the Admiralty had the unintended consequence of overcommitting the British navy to France.

The creation of the alliance system did not in itself mean that war was inevitable — after all, defensive alliances during the Cold War were a deterrent to aggression. What emerges strikingly from MacMillan’s account is the frightening shift which took place in the mindset of Europe’s leaders. Increasingly, the politicians and the diplomats came to think in terms of military solutions. At the same time, the military leaders gained greater influence.

Railway timetables and military plans did not cause the first world war, as A. J. P. Taylor once suggested. But the fact that troops could be mobilised and countries invaded within days put pressure on rulers to make decisions far more urgently than ever before. The politicians and the military lived in separate silos, and the civilian leaders failed to control or make the effort to understand what the military was doing. German ministers erred in failing to ensure that Germany had more than one war plan in 1914. This was a modified version of the Schlieffen plan, which gambled on a rapid victory against France, and it was based on a disastrous under-estimation of the British army. In Britain, ministers turned a blind eye to the military discussions going on with France, allowing the soldiers to turn the entente cordiale into a military alliance.

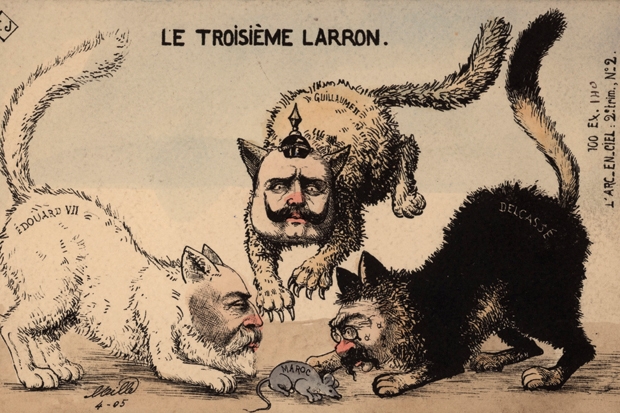

MacMillan is excellent on the diplomatic crises which shook the system after 1905. The Kaiser’s clumsy attempt to break the Anglo-French agreement by landing in the French colony of Morocco in 1905 only strengthened the entente, leading the British to begin military conversations with France. ‘What is frightening,’ comments MacMillan, ‘is how readily the countries involved in the Morocco crisis anticipated war.’ In each successive crisis — the Bosnian crisis of 1908, the second Moroccan crisis of 1911 and the Balkan conflicts of 1912–13 — war was only narrowly averted. Each time the powers became more jittery and the diplomatic groupings were tightened, until by 1912 they had become full-blown alliances.

Not all the civilian leaders wanted war, but the soldiers were gagging for it. In Austria-Hungary neither the 83-year- old Emperor Franz Joseph nor his heir, Franz Ferdinand, were warmongers. Neither of them saw war as the solution to the empire’s running sore — the problem of a resurgent Serbia. But the hawkish Chief of Staff, Conrad von Hotzendorf, urged military action. The awful irony was that Franz Ferdinand, who was murdered at Sarajevo, was probably the one man in the empire who could have prevented Austria going to war against Serbia.

When it comes to the killer question of Germany’s support for Austria in the crisis of July 1914, MacMillan takes a measured view. Germany’s ‘blank cheque’ promise to stand by Austria in the event of war with Serbia and also Russia was not, in her account, a deliberate attempt to start a war. Germany stands accused, however, of allowing war to happen. The distinction is perhaps a fine one, but MacMillan demonstrates that by 1914 the German elites saw war as inevitable and better sooner rather than later. Peace was no longer an option.

The case that Macmillan makes against the blame game for 1914 seems hard to answer. ‘The most we can hope for,’ she says, ‘is to understand as best we can those individuals who had to make the choices between war and peace.’ On the cosmopolitan world of pre-1914 diplomacy, where not only the monarchs but also the London ambassadors — Benckendorf (Russia), Lichnowsky (Germany) and Mensdorff (Austria) — were all cousins, the bookis superb.

At over 650 pages, this is a very long book, and it is written entirely from secondary sources. MacMillan spends rather too long setting the scene, and she is slow to reveal her arguments. The early chapters seem to rehearse over-familiar material. It might have helped if she had positioned herself in relation to the historiography — the historical literature on this topic is rich and vast, but she makes no attempt to review it.

When MacMillan picks up speed, however, she writes prose like an Audi — purring smoothly along the diplomatic highway, accelerating effortlessly as she goes the distance. This is a ground-breaking book, decisively shifting the debate away from the hoary old question of Germany’s war guilt. MacMillan’s history is magisterial — dense, balanced and humane. The story of Europe’s diplomatic meltdown has never been better told.

Comments