Leni Riefenstahl: what are we to make of her? What did she know? Often described as ‘Hitler’s favourite filmmaker’, she always claimed that she knew nothing of any atrocities. She was a naive artist, not a collaborator in a murderous regime. This documentary wants to get to the truth. But even if you’ve already made your own mind up – I had! – it’s still a mesmerising portrait of the kind of person who cannot give up on the lies they’ve told themselves.

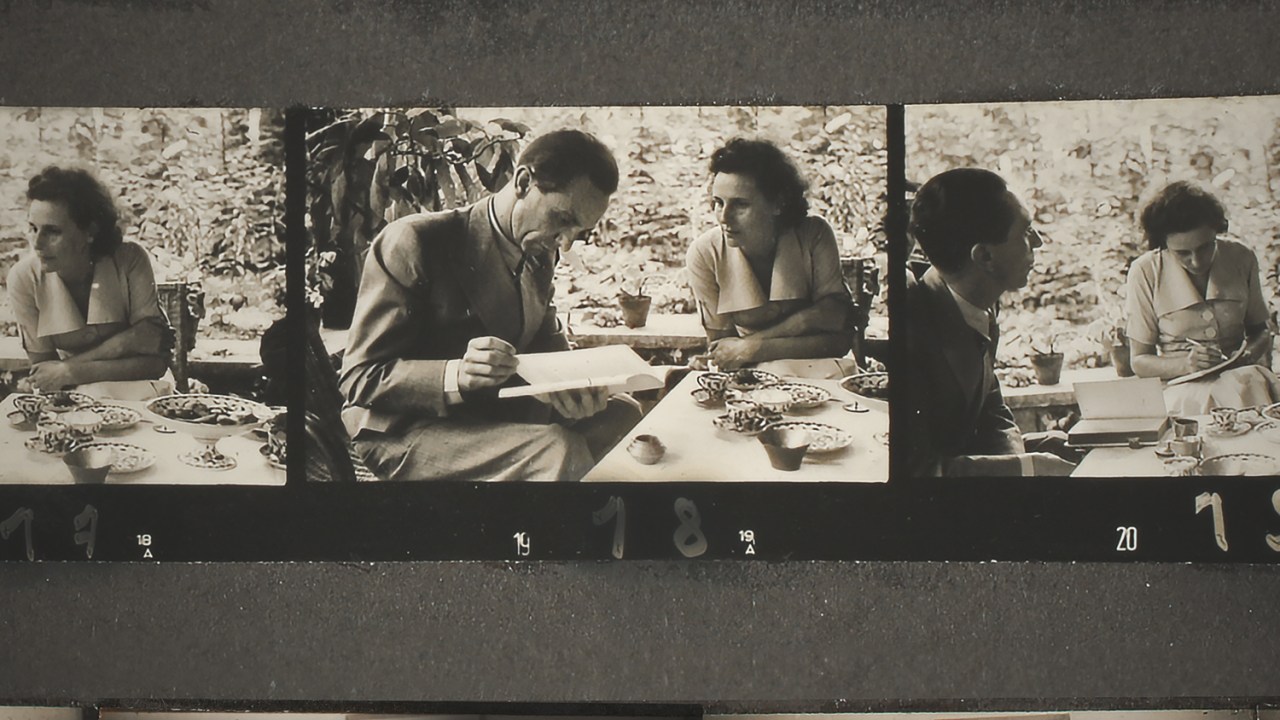

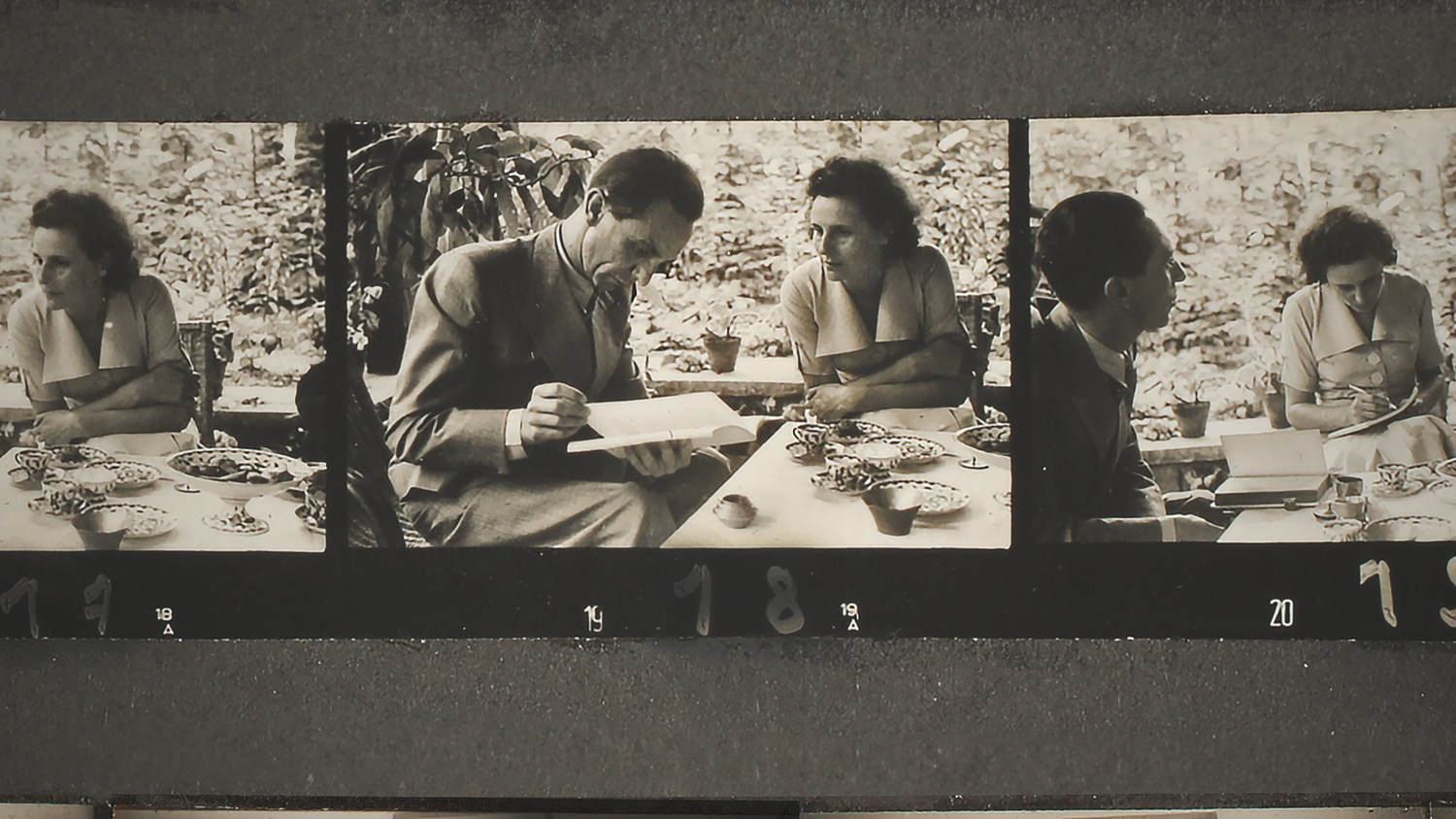

Riefenstahl died in 2003 at the age of 101. A striking, Garbo-esque beauty in her youth she looked like a haunted Fanny Craddock by the end. She left behind a huge archive amounting to 700 boxes of photos, footage, letters, writings, journal entries and recorded phone conversations, which director Andres Veiel has mined for this documentary. There are no talking heads or interjections. Instead, he uses the archive materials to recreate her life as dancer, actress, then director. Hitler called her the embodiment of German womanhood. They became friends and he asked her to direct documentaries glorifying the Nazi regime, including Triumph of the Will, filmed at the Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg in 1934.

She did not produce a newsreel as expected. Instead, she came up with a sweeping cinematic epic with Hitler portrayed as a rock-star god. She was next given a huge budget to film the Olympics in Berlin. She employed many unusual camera angles and the result was an ecstatic ode to physical perfection. (You can see her aesthetic influence in almost every perfume ad today.) Neither film was art for art’s sake. Both were designed to show German superiority to Germans and the rest of the world. Hitler was delighted. She became rich and famous.

But once the war was over she was finished. People had begun to ask questions. She would then spend the rest of her life denying she had known anything. It was a job, she would say. I never joined the Nazi party. I never said anything anti-Semitic. She subjected herself regularly to chat shows and TV interviews and was always self-justifying and unyielding and would often respond aggressively. When it’s put to her that Goebbels said in his diary that she visited him and Hitler ‘as an old friend’, she explodes with ‘this is untrue! That is a fantasy! I won’t be abused here!’ I had wondered why she didn’t choose to disappear from public view but then we hear a telephone conversation between her and Nazi architect Albert Speer, with whom she’d always stayed in touch, as you do. She asks him how much he is paid per interview. Two hundred marks, he tells her. She says she charges 5,000, minimum. There is, it turns out, money to be made from being a Third Reich celebrity.

The film uncovers new evidence but because she had carefully edited her archive, most of it is as circumstantial as it’s ever been. The most telling moment is taken from an earlier documentary (Ray Müller’s 1993 The Wonderful Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl) where they are watching a scene from Triumph of the Will and she excitedly points out her innovative camera work, waves her arms in time to the music, and lights up from within. I have never seen anyone so lit up from within. She finds it orgasmic. How could anyone be in any doubt?

There has never been a smoking gun when it comes to Riefenstahl, and Veiel doesn’t find one, but if Hitler had won, what I would bet on is this: she would not have been so keen to distance herself – at all.

Comments