The KGB might not have known much about modern art, but they knew what they liked. For instance, at what came to be called the ‘Bulldozer show’ of 15 September 1974, the Soviet secret service instructed a small militia of off-duty policemen to besiege an unofficial exhibition being staged by a group of underground artists in a field on the outskirts of Moscow. As James Birch recalls, KGB goons ‘attacked the show, using bulldozers and water cannons. Artists and onlookers were beaten up, some paintings were set on fire, other works were thrown into tipper lorries where mud was piled on top by diggers’. Surviving artworks were ‘driven off to be buried’ in an unknown location. An uncompromising response, perhaps — but then again, which artist in the West could hope to provoke such a spirited critical reaction?

By 1986, Birch, an enterprising young gallery owner with a showroom at the unfashionable end of the King’s Road, hoped that attitudes in the increasingly liberated USSR might have relaxed enough to permit an exhibition of contemporary British art there. At the time he was ambitiously promoting the work of the Neo Naturists, a group of ‘mercurial young artists’ whose manifesto outlined their commitment to ‘taking their clothes off for the sake of it’. The group, which included the transvestite ceramicist Grayson Perry, would paint primitivist designs on to their naked bodies and then roll around on blank pieces of paper, or turn up pre-decorated to other people’s parties where they would burst into song and ‘suddenly disrobe’, invariably frightening off the other guests. Their work had an undeniably stark quality, and Birch believed in it. But ‘was Moscow ready for the Neo Naturists?’

No, it wasn’t. As Birch recalls in Bacon in Moscow, a first exploratory trip to the Soviet Union revealed an artistic sensibility still disconcertingly ‘frozen in time’, the country’s leading painters apparently ‘unaware of whole areas of 20th-century modernism’, its cultural institutions unfathomable bureaucracies. Then, of course, there were those bulldozers, perhaps still lurking in the shadows with their engines running; and since the Neo Naturists used their own bodies for canvases, the premonition of Grayson Perry being slowly pressed into the earth by a dumper truck must have weighed heavily on Birch’s conscience. That would give a whole new, less glamorous meaning to the term ‘underground artist’.

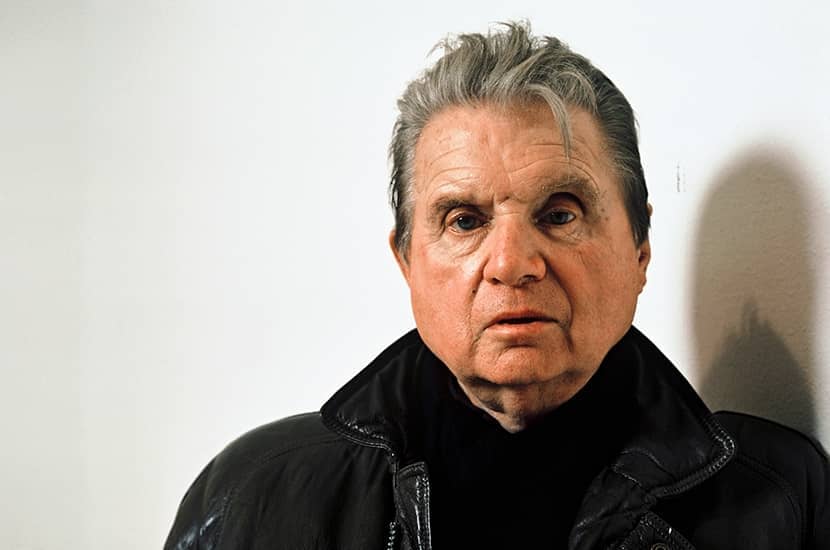

In a despairing attempt to salvage something of his project, Birch instead proposed a major retrospective of an established western artist, tentatively suggesting Francis Bacon, a close family friend, as its subject, though all the while harbouring mis-givings: ‘I could hardly think of a less Soviet-friendly artist.’ While certainly a committed socialiser, Bacon was no socialist; he was, admittedly, devoted to the betterment of the proletariat, though in Bacon’s case this involved lavishly indulging the coterie of East End petty criminals and rough trade who participated in his complicated sex life and lived off his masochistic generosity. ‘He may call Margaret Thatcher a silly cow,’ Birch warned, ‘but he still votes for her.’

However, to Birch’s delight, Bacon proved gung-ho. Around the same time, Birch bought a gallery below the Colony Room, and, as a matter of social inevitability, became one of the many energetic young men borne about town by Bacon and the tide of booze that swept him along on his endless champagne benders. (‘Champagne for my real friends, real pain for my sham friends!’ as Bacon used to say, raising a toast.)

Bacon cancelled travelling to Moscow at the last moment for fear of being kidnapped on the Russian railways

Bacon in Moscow is a forthright and enjoyably strung-out anecdote about the gallerist’s hidden plight: a record of the two years of intense anxiety, logistical set-backs and flights of diplomatic imagination required to persuade Bacon, his private gallery (the Marlborough) and the USSR’s Union of Artists to co-operate in the pursuit of a shared aim. ‘Francis was a very honourable man, but he could be changeable.’ He was easily distracted whenever conversation took a practical turn. An ‘apparently innocent’ organisational meeting could inexplicably degenerate into a ‘day of intense drinking’. What one really needed in Bacon’s presence — in addition, it seems, to a couple of spare livers — was ‘a certain ease of attitude’.

The denouement of the book — which sees Bacon’s 1988 Moscow retrospective, the first of any living western artist in decades, open to the world’s press — discloses a few telling failures of nerve. Bacon, his bags already packed, his Russian-language tapes primed in the Walkman, was dissuaded from travelling at the last moment, partly due to the jealous influence of his confidant, the art critic David Sylvester, who terrified him into believing he would be kidnapped and ransomed while using the Russian railways. The Soviets, for their part, refused to display one of Bacon’s greatest works ‘Triptych’ (1972), on the grounds that its central panel, which depicts gay sex, was ‘too pornographic’. Or, as one of Birch’s Soviet counterparts explained delicately, such ‘cock-exalting canvases would never be understood by the Soviet public’ (though the real worry was, as ever, that they would be understood all too well).

In addition to being a gallerist’s remembrances, Bacon in Moscow is an enjoyable portrait of two insular, rather dysfunctional societies, both awash with drink in their long dying day: Soho and the Soviet Union. Birch is a likeable, unselfconscious memoirist, and cheerfully celebrates his coup: despite mutual suspicion and political hostility, great art managed to ‘slip through the battle lines’ drawn by world powers. Over six weeks, 400,000 people saw Bacon’s retrospective. Being Soviets, they were luckily used to standing in line for bacon.

Comments