Religious conversions do not, for the most part, make for good anecdotes. An exception can be found in Patricia Lockwood’s memoir Priestdaddy, which describes the author’s father Greg’s road to Damascus experience in a nuclear submarine off the coast of Norway, where he watched The Exorcist 72 times:

That eerie, pea-soup light was pouring down, and all around him men in sailor suits were getting the bejesus scared out of them, and the bejesus flew into my father like a dart into a bull’s eye.

It was, Greg boasted, ‘the deepest conversion on record’.

The 12 conversions explored by Melanie McDonagh in this absorbing study are less Halloween and more slo-mo than this, the result of a gradual accretion of faith which cannot, as Cardinal Newman said of his own defection to Rome, be ‘propounded between the soup and the fish’. Several are defined by a wearisome matter-of-factness. ‘I felt no emotion about it,’ shrugged Oscar Wilde’s former lover Lord Alfred Douglas, who converted in 1911 after reading Pope Pius X’s Encyclical Against Modernism. ‘In some ways I felt that to become a Catholic would be a tiresome necessity.’

Evelyn Waugh’s conversion, which he rarely talked about, was similarly devoid of emotion. ‘What little he did tell,’ said his friend Christopher Sykes, ‘indicates a rational approach to the faith.’ The poet John Gray, who converted in 1890 after stumbling upon a mass consisting of six peasant women and a slovenly priest in a ‘small wayside chapel’ in Brittany, went through his instruction ‘as blindly and indifferently as ever anyone did’. The philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe discovered her Catholicism, aged 15, while reading The Everlasting Man by G.K. Chesterton, himself a convert. ‘It came to me that I believed in God and ought to pray,’ she said of the experience. McDonagh focuses less on the conversions themselves, given their largely non-verbal nature, than on their influence on the life and work of the converts.

In the first six decades of the 20th century, half a million Anglicans in England and Wales crossed over to Rome, including, writes McDonagh, ‘some of the most remarkable artists and writers of the period’. Among them were Oscar Wilde, who converted on his deathbed in 1900, after a long flirtation with the church; Gwen John, who converted when her affair with Rodin ended (‘O God, transform me in this suffering, I beseech thee’); and the poet and artist David Jones.

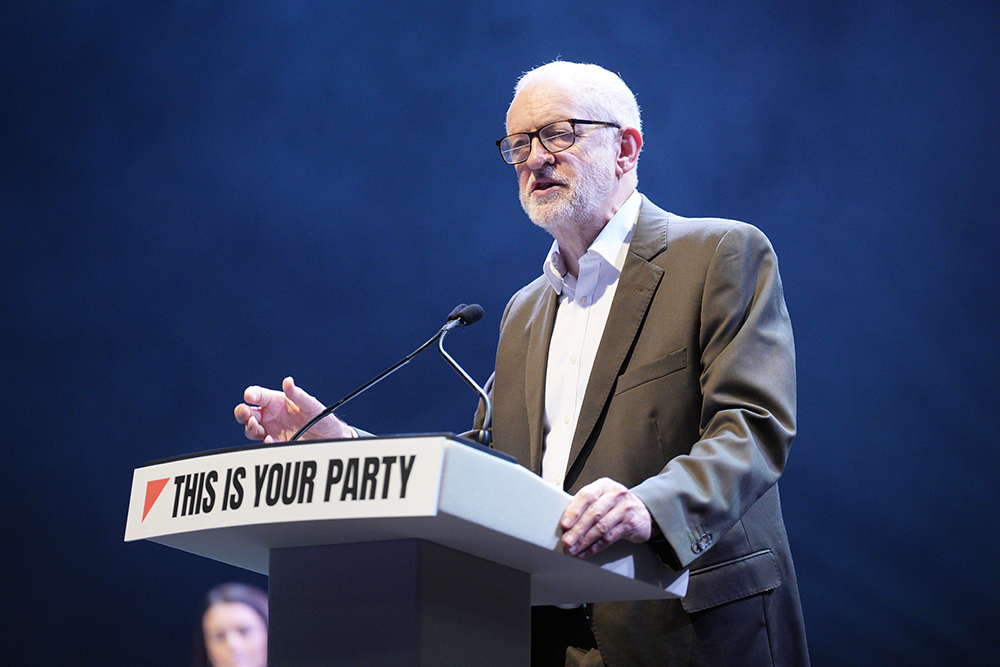

Oscar Wilde converted on his deathbed, after a long

flirtation with the church

McDonagh begins, however, with the role of Catholicism in the cultural renaissance of the 1890s, thought by W.B. Yeats to be a poetic reaction against Victorianism. She then backtracks to Newman’s conversion in 1845 where, with great delicacy, she combs through the differences between Catholicism and Anglo-Catholicism.

It was Newman’s example which inspired R.H. Benson, the son of the Archbishop of Canterbury and future chamberlain to Pope Pius X, together with ‘99 out of a hundred educated converts’, as he put it. Benson’s experience of conversion was, however, the exact opposite of Newman’s. While Newman described his submission to Rome as ‘like coming into port after a rough sea’, Benson compared it to going ‘from the familiar and the beloved and the understood into a huge, heartless wilderness’. An account of Benson reading his supernatural tales to students at Cambridge provides McDonagh’s only exorcist moment. The diplomat and writer Shane Leslie recalled:

I can see him sitting in the firelight of my room at King’s unravelling a weird story about demoniacal substitution, his eyeballs staring into the flame, and his nervous fingers twitching to baptise the next undergraduate he could thrill or mystify into the fold of Rome.

Many of the homosexuals who converted in the 1890s, including Aubrey Beardsley and Robbie Ross, were drawn to the ideas of transgression and redemption, grace and atonement, together with the comfort of having one’s sins forgiven. If the Protestant position, as Waugh said, is that ‘I am good; therefore I go to church’, the Catholic position was ‘I am far from good; therefore I go to church’. Later converts described the need for stability in an uncertain world. ‘I want to be a Catholic now,’ wrote Graham Greene to his fiancée. ‘One does want fearfully hard for something firm & hard & certain, however uncomfortable, to catch hold of in the general flux.’ For the soldiers who converted, there was the possibility of death to consider, and their discovery of Catholic Europe.

Other converts were moved by the return to the old religion of England. The writer and Russophile Maurice Baring wrote to a friend:

I went to mass this morning and it was nice to think I was listening to the same words, said in the same way with the same gestures, that Henry V and his ‘contemptible little army’ heard before and after Agincourt.

For me, the most powerful of the conversions examined here was that of David Jones, who witnessed his first Catholic mass on a wet Sunday in 1917, when he was serving in France and looking for firewood. Through a crack in the wall of a deserted farm building he saw two candles and half a dozen infantrymen kneeling on straw. Everything was silent and the men were as still as shadow puppets. In a ‘wasted land of ubiquitous mud and rusted iron’, Jones had discovered ‘a great marvel’; it was ‘one of the most numinous experiences of his life’. Like Baring, Jones found in Catholicism a ‘continuity with antiquity’, but he also found himself as an artist. ‘I’m a Catholic,’ he later said, ‘as all artists must be.’ The eucharist, he believed, was both a symbol and the real thing: this was the transubstantiation of art.

Gwen John similarly came to Catholicism as an artist: ‘God has taken me to enter into Art as one enters into Religion,’ she wrote. And it was only when Muriel Spark converted that she discovered her voice as a novelist, thus discrediting George Orwell’s foolish suggestion that the novel was a Protestant art form, because ‘the atmosphere of orthodoxy is always damaging to prose’.

While for some converts Catholicism made life bearable and for others it made art possible, for Chesterton, if embraced by all, it would rid England of the ills of ‘Capitalism, crude Imperialism, Industrialism, Wrongful Rich’ and ‘Wreckage of the Family’.

McDonagh ends with the conversion of Siegfried Sassoon in 1957, five years before the modernisations of the Second Vatican Council would destroy, according to David Jones, the greatest and most sacred art form that western culture had produced. The country clearly agreed with him: there were only 6,046 converts in 1970 and 1,976 in 2022. Today’s conversion stories are more likely to describe the transition from one gender to another than between one world and the next.

Comments