When David Cameron started contemplating life after Downing Street, he settled quite quickly on a model of what it should look like. He would stay on the backbenches, providing advice and wisdom to whoever came after him, earn a little bit of extra money while still working as an MP, and continue in public service with charities and others. In 2016, he outlined his approach to me as we sat in a cafe in Witney, and I wrote it up in my book, Why We Get The Wrong Politicians:

He mourned the number of former ministers who had departed at the 2015 election, and suggested that you could do other things alongside being an MP if you did fancy a little bit more income to make up the ministerial salary you had lost. ‘John Major is a better model than Blair,’ he told me, as we discussed what sort of ex-prime minister he wanted to be.

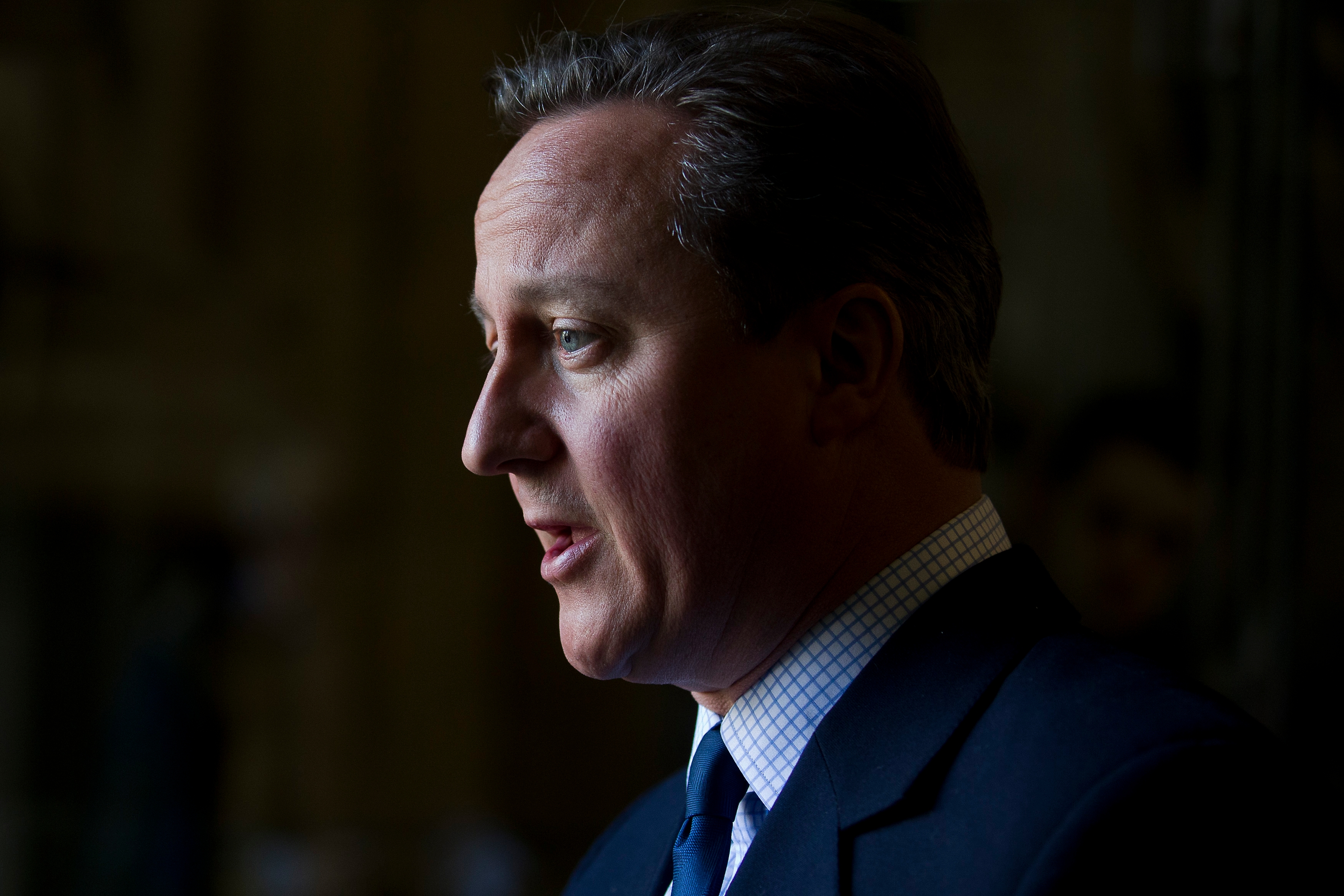

In his own book, Cameron describes the experience of ‘going from prime minister to plain old David Cameron’

It seemed an admirable plan: use his experience to inform politics in the future, avoid an ostentatious spree of earning money, and develop a reputation as a measured grandee. Initially, Cameron seemed content to stick to this when his best-laid plans of leaving on his own terms collapsed just a few weeks later with the shock EU referendum result and his resignation. Cameron did retreat to the backbenches and watched Theresa May’s election as his successor. It was only at this point that he seemed to realise how inconvenient this new life could be.

For one thing, the new prime minister wasn’t going to honour every aspect of his legacy, and he would end up being watched for his reactions to May abruptly changing policies. His friend George Osborne was sacked by May and told to spend more time getting to know his party. Both of them looked much smaller as they moved through parliament without their entourages — and without much to go to. There was no high level meeting to sweep into, no stacked timetable of engagements, no coterie of backbenchers wanting to suck up to you in the hope of a promotion. In his own book, Cameron describes the experience of ‘going from prime minister to plain old David Cameron’ as being a ‘blunt’ reminder of the fact that in British democracy, you have no title as an ex-prime minister, unlike former US presidents.

He also writes that it was only when he returned to the Commons for a debate on Trident that he:’realised what a difficult existence being an ex-PM in the House of Commons was going to be’ and that ‘friends persuaded me that my continued presence would be bad for the new PM and miserable for me’. So he quit, and a little later, so did Osborne.

Outside parliament, Cameron could still have stuck to parts of his plan to remain an elder statesman, but in Greensill Capital it seems he found the undoing of the rest of that model he’d outlined back in 2016. Now his reputation will always be tarnished by what he did after leaving office — which turns out to have been the very opposite of what he’d said he would do. Before becoming Prime Minister, he was reported to have remarked to a friend ‘how hard can it be?’ It turns out that he hadn’t appreciated how tricky life after office could be, either.

Comments