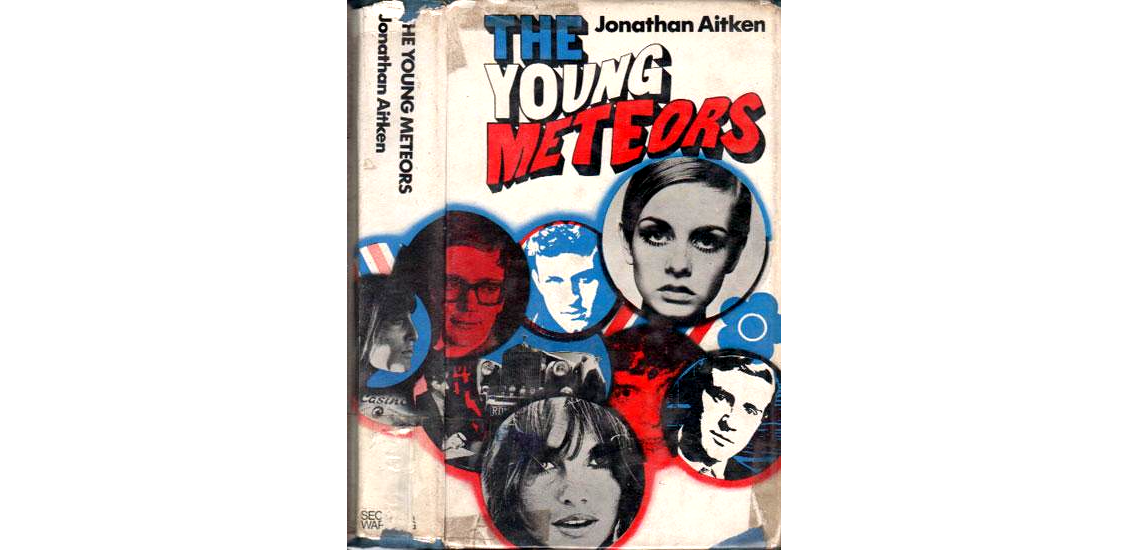

I am not bragging when I say that 56 years ago I was a young meteor. No: it is official. In 1967, Jonathan Aitken, then a young journalist on the Evening Standard (his uncle, Lord Beaverbrook, owned it at the time) wrote a book about the upcoming young movers and shakers in London – the stars of the Sixties (to mix celestial bodies). The Young Meteors it was called, and I was one of them.

At that time, I was 27 years old and the fashion editor of the Sunday Times and Aitken put me in as one of the three powerful influencers in that world. (The others were Marit Allen of Vogue and Georgina Howell of the Observer – both dead now, sadly.)

Aitken lauds the women journalists of the Sixties but is puzzled by the lack of female editor

The Young Meteors was really just a glorified list of successful men and women who shaped the Sixties – that extraordinary era that changed everything. This was the decade that saw the arrival of the Pill; the legitimisation of homosexuality; the abolition of hanging; the Oz and Lady Chatterley’s Lover trials. It was the dawn of a new kind of satirical humour (Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, David Frost, On the Fringe and That Was the Week That Was); a new elite (with the marriage of Anthony Snowden and Princess Margaret, for instance); a fashion revolution; the birth of the boutique; The Beatles, The Rolling Stones…

For anyone doing research on the Sixties, the book is the Bible. It came a little too early for some important figures: Germaine Greer published The Female Eunuch three years later and Carmen Khalil founded Virago, in 1973. Don McCullin, described by Aitken as a ‘top young photojournalist’, was world-famous within what seemed like minutes.

The book was prompted by the Time magazine cover of April 1966 on which, across a collage of famous British faces, ran the bold headline LONDON: THE SWINGING CITY. Swinging London was born.

I remember being so wildly excited at the idea of being a young meteor that I invited the 24-year-old Aitken to lunch with my sister and brother-in-law before the interview. I hadn’t a clue about cooking and for some obscure reason, I decided to make a stuffed pork fillet. My sister and I rehearsed the recipe in advance and – shock horror! – the fillet on the serving dish looked exactly like a horse’s willie. On Interview Day we cut the fillet up into modest pieces…

I met Aitken, now reincarnated as an ex-convict and priest, again recently – over half a century since we did that interview. He didn’t remember the pork fillet but he did remember my sister being very pretty, ‘Erm… not that you weren’t very pretty too’, he added, kindly.

His involvement with the book came about when an American publisher, Athenaeum, was looking for a bright young thing and Aitken’s agent at Curtis Brown suggested him. ‘I thought the idea was a bit of a hoot’, he says, ‘not a very serious subject, but they were offering an advance of $8,000 which was a huge sum, so I decided to do it.’

Already several steps up the ladder in journalism (following Eton, Oxford, and a stint in law), he saw his future in serious politics. He was not interested in being a young meteor – but nor was he just a bystander. ‘Right from the start, I wasn’t sure what side I was on. The people I was writing about – photographers, models, fashion editors, film stars, actors and so on were exciting but I worried at the superficiality of it all… I worried about the decline of the industries which had made Britain great. Where were they? Having said that, I enjoyed being a spectator – having a ringside seat at the young meteor circus. And the 1960s was an exciting time… bliss was it in that dawn to be alive and all that.’

Aitken gave a good deal of space to fashion – writing about Mary Quant, Biba and the other emerging young designers – he even mentions Vanessa Denza, the 21-year-old buyer at Woollands in Knightsbridge (now demolished) the first store, as opposed to a boutique, to sell the clothes that were revolutionising the way we dressed. (A memorial for Vanessa Denza took place earlier this month in London.)

This was a golden age for fashion photography, now increasingly undermined by the internet. Aitken notes that photographers became posh when Tony Snowden married Princess Margaret – he once heard someone describe David Bailey as the ‘Aly Khan of the clicking shutter.’ Aitken was charmed by the 17-year-old Twiggy, who was ticked off during the interview by her manager for biting her nails.

Aitken lauds the women journalists of the Sixties but is puzzled by the lack of female editors. ‘The contribution to British journalism by women has been so considerable that I sometimes wonder why Fleet Street’s amazons have not united in a feministic take-over bid for the entire industry.’

Among male editors, his meteors were Jocelyn Stevens of Queen magazine, Richard Ingrams of Private Eye and Bruce Page, Hunter Davies and Mark Boxer – all colleagues at my old alma mater, the Sunday Times – ‘a paper in embarrassingly superior position among British newspapers’, writes Aitken. ‘Top young photo-journalist’ Don McCullin joined the other meteors there the year Aikin was working on the book. In advertising, one of Aitken’s meteors was Peter Mayle, a copy chief at a major agency who later became famous for his book A Year in Provence.

For politics, Aitken conducted a mini survey and discovered that out of 50 people, 82 per cent said they had no confidence in any of the then-leaders – though 46 per cent thought Roy Jenkins would make a better PM than anyone else. George Brown was popular but as a comedian rather than a politician.

He cited few political meteors but among them were Peter Walker (Aitken went on to work for Slater Walker in the 1970s) David Steel, Roy Hattersley and he bet, too, on Anthony Lester with his Campaign Against Racial Discrimination.

Using the jargon of that time, Aitken says he was square: ‘At least when I had my clothes on,’ he adds with a twinkle. Back in the day, he had various high-profile girlfriends, including Antonia Packenham (now Lady Antonia Fraser), and Carol Thatcher. It has been said that as an MP he never left the backbenches under Mrs Thatcher because of that broken romance.

Aitken confesses that outside his own area of experience – law, politics, business – he didn’t have much of a clue about which meteors he should be talking to. He picked the brains of friends and girlfriends, doing most of the interviews himself but delegating a handful. Towards the end, when the book was nearly finished, the Evening Standard sent him to report on the Vietnam War and he found himself telexing the final chapters from the press centre in Danang. By now the manuscript was far too long and he had to leave the publishers to make the cuts. This led to some awkwardness when the publicity people at Secker & Warburg, the British publisher, sent postcards to dozens of young meteors to let them know they were in the book – but it turned out they had ended up on the cutting room floor.

Comments