This column comes to you from Auckland Castle, former palace and hunting lodge of the Prince Bishops of Durham. We, the Rectory Society, are here by kind permission of its saviour, Jonathan Ruffer, celebrating our 20th anniversary. Jonathan rescued the castle not from the heathen but from the Church of England. The last Anglican bishop to inhabit it was Justin Welby, in his brief year at Durham before being translated to Canterbury, but it had been run down for many years before that. Bishop Auckland is in one of the poorest parts of England but it did not occur to the Church authorities to use the heritage of this astonishing place to minister to the poor. Here is history and art and architecture and parks and gardens and the largest private chapel in Europe and the river Wear and a town at its gates, yet the place fell asleep with a Do Not Resuscitate notice attached to its recumbent body by the Church Commissioners.

Under Ruffer, it has woken like a King Arthur of the north, reclaiming the leadership of this part of Christian England. First he bought Zurbaran’s wonderful paintings of Jacob and his sons and then restored the dining-room which the enlightened and profoundly rich Bishop Trevor built specially for them in the 1750s. A philosemite, Trevor bought the pictures to further his support of the ‘Jew Bill’, which tried to confer proper citizenship rights on Jews. Then Ruffer bought the whole castle, beautified it, established a Museum of Faith which tells the story of all religion in Britain from prehistoric times to the present, installed a Spanish gallery, a museum of mining, told the history of England in an annual summer pageant called Kynren, got the gardens rewalled and blooming, and spent well over £100 million of his own money in the process. As we arrived, a party of excited schoolchildren departed, having got answers to questions you daren’t ask teachers now, like: ‘What was the Reformation?’

As part of the entertainment, we had an hour of singing in Cosin’s 17th-century chapel hymns that had been written in parsonage houses, cheating a bit at the edges. Charles Wesley, Isaac Watts, Mrs C.F. Alexander, George Herbert, John Henry Newman and John Newton all got a look in, as did Cosin himself. I had held one hymn in reserve in case we had time, and we did. This was ‘From Greenland’s Icy Mountains’, by Reginald Heber. We used to sing it with gusto at my village primary school, but it is now cancelled because it says that in un-Christianised lands, ‘The heathen in his blindness bows down to wood and stone’. It is remarkably vivid about exotic climes, however, and Heber wrote it before he had been to them. He did so not in his own rectory but in that of his father-in-law, who asked him to compose a hymn for the meeting of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel the following day. Heber did so in 20 minutes. Later, he became Bishop of Calcutta, a diocese which included all India, southern Africa and Australia. He died in 1826, sadly young, in a bath in Trichinopoly after a hot day’s missionary work. Such are modern conditions that it is time for developing-world Christians to write a Heber-style hymn in reverse about how to bring the true faith to darkest England.

I had decided not to include any hymns by F.W. Faber, Newman’s fellow Oratorian and hated rival. To my taste, at least, they are too floridly emotional. On Monday, however, as the House of Lords debates the Hereditary Peers Bill (3rd Reading), which will expel all such peers, I shall take comfort in Faber’s lines from ‘There’s a wideness in God’s mercy’: ‘There is grace enough for thousands/ Of new worlds as great as this;/ There is room for fresh creations/ In that upper home of bliss.’

The Court Circular reporting the state banquet for President Macron at Windsor Castle last week listed those who ‘had the honour of being invited’ and explained who they were. The list included ‘Sir Michael Jagger (Musician) and Ms Melanie Hamrick’ and ‘Sir Elton John (philanthropist) and Mr David Furnish’. I wonder how those descriptions were settled. Is Sir Michael not a philanthropist? Is Sir Elton not a musician?

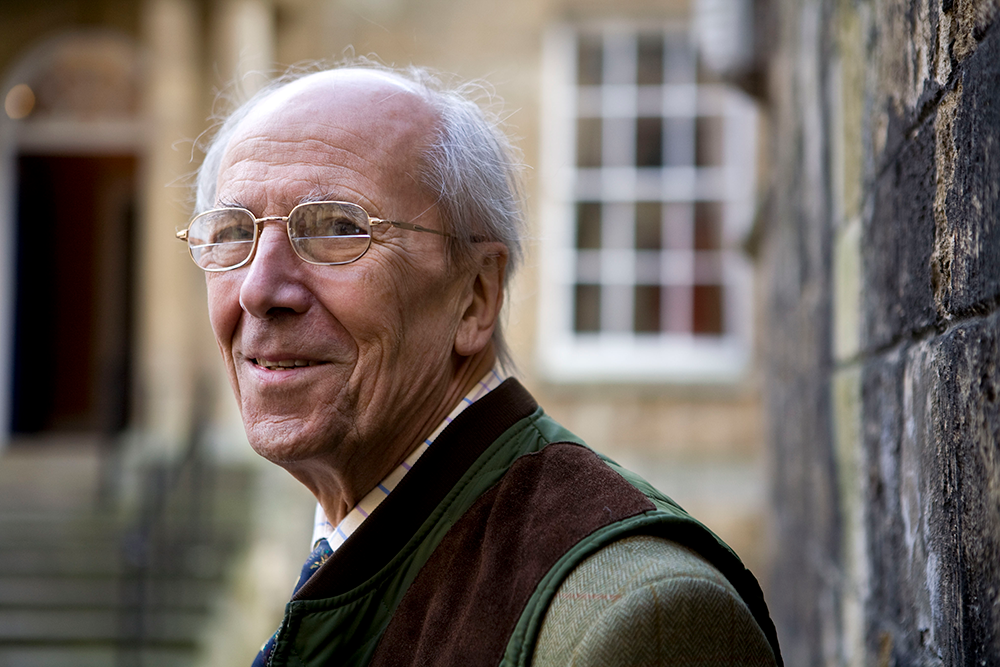

One thing I shall miss about Norman Tebbit is his way with words. They had unusual economy and exactness. In November 1990, between the two ballots of the Conservative leadership campaign, I heard him being interviewed on the BBC. Michael Heseltine had won fewer votes than Mrs Thatcher in the first ballot but nevertheless enough to force her to resign. He therefore needed more votes to win on the second. ‘They say there’s an avalanche moving for Mr Heseltine,’ said the BBC interviewer. Every other politician would have accepted this dead metaphor unthinkingly. Not Norman. ‘First time I’ve heard of an avalanche going uphill,’ he said.

When editing this paper in the 1980s, I invited Tebbit and Jimmy Goldsmith to the same lunch. They had not met before and got on very well. Both complained about the lack of impressive figures in public life. ‘We need more eelan,’ said Norman in the accent of his native Ponders End. I could see that Goldsmith, who was half-French, did not understand what Tebbit was saying. ‘Élan,’ I muttered to him, like an interpreter at a summit. Jimmy’s eyes lit up in comprehension, and agreement. The two men might have pronounced it differently, but both had it.

‘Hope for the future’ said the T-shirts and banners for a conference about something or other taking place in the Methodist Central Hall as I walked past last week. The pedant in me always dislikes this phrase: how can hope be for anything other than the future? But then I reflect that if the future is truly bleak, we must place all our hope in the past.

Comments