Andrew Roberts

The most important moment came on 11 November 1975 when her governor-general in Australia, Sir John Kerr, dismissed the Labour government under Gough Whitlam, doing so in her name. Although the Queen knew nothing about it before it happened (indeed, she was asleep at the time), it reiterated the vital constitutional principle that there is a power above politicians, even elected ones as in Whitlam’s case. Whitlam had driven Australia to the brink of economic and social collapse, but Kerr saved the country using the Queen’s royal prerogative. His decision was enthusiastically endorsed by the Australian people at the subsequent general election, with a landslide victory for Malcolm Fraser. Even while she slept, therefore, the mere existence of the Queen’s prerogative rights reminded the world that her politicians are the servants of both her and the people, not the masters.

Peter Hitchens

1997 must now be seen as the year the fatal blow was struck at the monarchy. Two things sum this up. Both were to do with Blairism. The first was the general acceptance that New Labour was right to abolish the hereditary peerage, at worst a harmless survival and at best an obstacle to the tyranny of the party machines and their whips. Nobody significant could be bothered to defend it on principle. Yet the change was a frontal assault on the idea that constitutional power can legitimately be inherited. From that moment onwards, the Queen’s influence depended purely on her own personal popularity. Her heirs and successors, if they cannot attain popularity, or if they lose it, will have no generally accepted entitlement to sit on the throne. The BBC’s portrayal of Tony Blair’s arrival in Downing Street, including a fake crowd of Labour supporters waving Union flags in a street which the public are forbidden to enter, was the inauguration of a president in all but name, as everything which followed showed.

Robert Tombs

Though tempted to choose a year of uplift – the Falklands in 1982 or the 2016 referendum perhaps – I cannot escape the gravitational pull of 1963, Philip Larkin’s ‘annus mirabilis’, the climax of our cultural revolution. The Queen must have hated it. Kim Philby (Westminster and Cambridge) was belatedly exposed as a traitor. John Profumo resigned after lying about his affair with Christine Keeler, soon one of Britain’s most famous women. The Beatles became a sensation. Oh! What a Lovely War opened, ridiculing patriotic sacrifice. The media-friendly Bishop of Woolwich, Dr John Robinson, published Honest to God, a bestseller criticising traditional religion and morality: ‘Nothing can of itself always be labelled as “wrong”.’ Dr Alex Comfort, poet and former conscientious objector, appeared in a BBC series promoting sex as healthy recreation. The miniskirt was christened by Mary Quant. ‘Supermac’, now the butt of derision, left Downing Street. The long Victorian Age ended, and we suddenly seemed a different people. ‘The upper classes,’ declared one journalist, ‘passed unquietly away.’ But at least one remained, despising fashion: and she still reigns over us, holding the strands of history together.

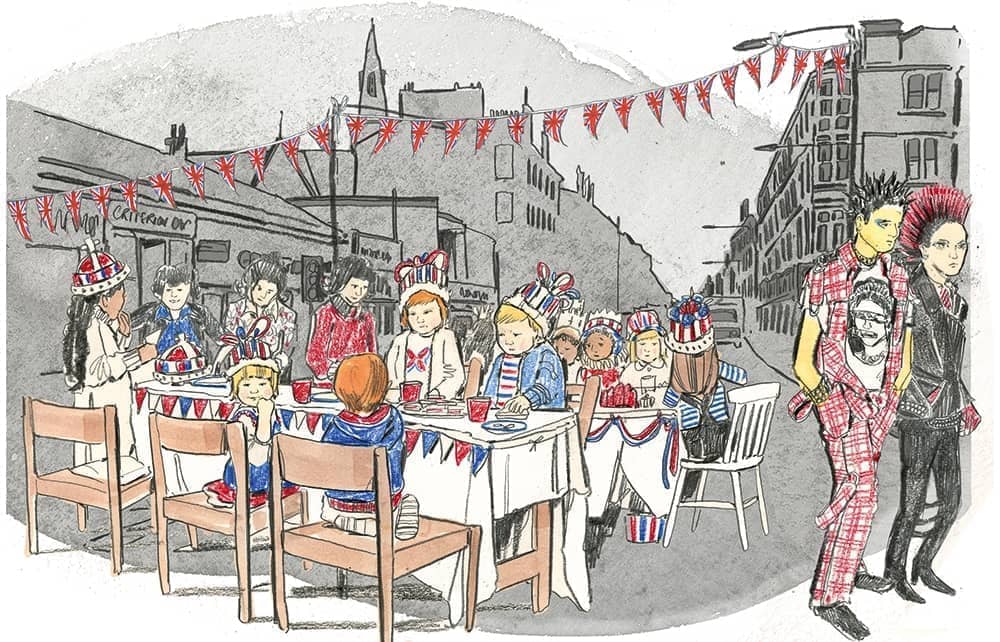

Sinclair McKay

1977 was the final flowering of the hearty New Elizabethan sensibility: Blue Peter-ish jubilee street parties, papier-mâché pageants; the last time it would be possible to imagine some form of genuinely unified, sincere – and slightly silly – national celebration. By 1977, something was hardening in the nation’s heart: the leaden recognition that the UK was no longer great but instead tawdry and dismal and exhausted – a series of brutalist shopping precincts punctuated with seamy cinemas showing Swedish Nurse pornography double bills. Inflation was 16 per cent and seemed insoluble. Industry – a resentful state production line of brown cars – was class war. Mr Callaghan’s Labour government, not long back from the IMF, had to gingerly introduce us to the idea that Keynesianism wasn’t working. The shock of the Sex Pistols and their gobbing anthem ‘God Save the Queen’ was partly that it wasn’t such a great shock. England had already stopped dreaming. Optimistic regeneration would come again; but past this point, New Elizabethan innocence was impossible. The next generation of royalty – ‘Charles and Di’ onward – acquired the onyx aesthetic quality of American soap opera. We looked at the tea towels and saw the kitsch.

Antonia Fraser

The current one, 2022. This is because two bold, brave decisions were taken on behalf of the monarchy. First, Her Majesty announced that the Prince of Wales’s wife, known as the Duchess of Cornwall, would become queen when her husband ascended the throne. The official role of the former Camilla Parker Bowles in the royal family had begun with her marriage in 2005 in an atmosphere still clouded by grief and other less sympathetic emotions following the tragic death of her predecessor (hence she did not take the title ‘Princess of Wales’). It was understood that when Prince Charles succeeded, she would be some kind of princess consort. That was then. Years have passed in which the Duchess has proved herself an agreeable, hard-working, intelligent member of the royal family. Now the Queen has swept aside the past in favour of the future. Camilla will be queen. The second bold decision was to remain Queen Regnant herself, despite her advancing age. Long live Queen Elizabeth II!

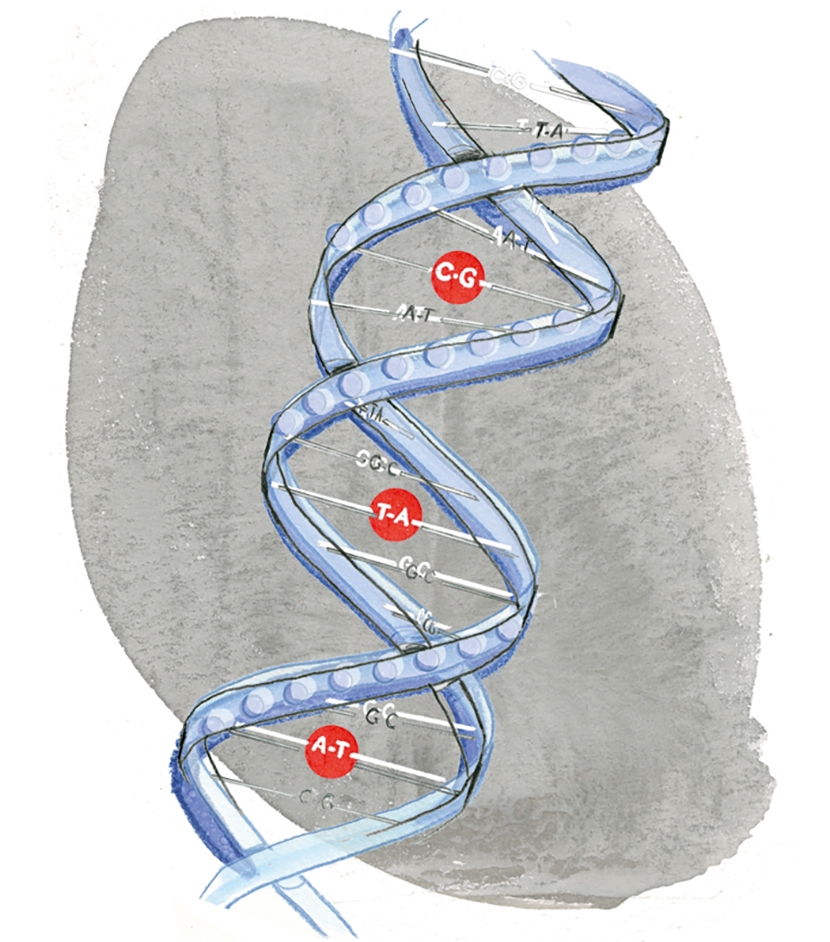

Matt Ridley

The most significant year of the Queen’s reign is 1953, not because it saw the coronation that led to the longest reign, nor because it saw the climbing of Mount Everest, let alone because of the death of that ogre Stalin, but because of what happened in Cambridge on 28 February that year. The sudden and utterly unexpected discovery by Jim Watson and Francis Crick of the double helix of DNA, and hence that the key difference between living and non-living things is digital information written in a universal four-letter code, is in my view the most surprising and portentous eureka moment of all time, beating evolution, gravity, relativity, America, the atom and all the rest into a cocked hat.

Niall Ferguson

I was 13 in 1977, the year of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. It was quite a time to be a bored Glaswegian teenager. The entire British economy was in the doldrums, but the shipyards and steelworks of Clydeside were in terminal decline. Scottish nationalism was enjoying one of its periodic surges, but the Glasgow gangs were more interested in mimicking the sectarian strife of Ulster. In short, we appeared to be living through ‘The Break-Up of Britain’, the title of a widely read tract by Tom Nairn. So I still recall with a frisson the first time I heard the Sex Pistols’ ‘God Save the Queen’, which perfectly expressed my adolescent sentiments. ‘God save the Queen / The fascist regime / They made you a moron / Potential H-bomb…’ Nothing in today’s popular culture remotely comes close to its incandescent ferocity. The reason 1977 was the most significant year in the Queen’s reign is quite simply that she – and the monarchy – survived it. ‘There is no future,’ snarled Johnny Rotten, ‘in England’s dreaming.’ So it seemed. And yet there was, and still is.

Joan Bakewell

1997 was the year Britain was swept by change. As Prime Minister, Tony Blair was to oversee a decade of progressive policies and civic prosperity. Whether the Queen approved or not, she could hardly be unaware of the strong change of direction: devolved governments for Wales and Scotland, more police, doctors, midwives, the introduction of minimum wage, better deals for pensioners, more young people at universities than ever before, the abolition of Clause 28, and the introduction of civil partnerships. The greatest of the Blair government’s early triumphs was the Belfast Agreement negotiations (initiated by John Major) – a stunning record of political commitment. The weekly encounter between Her Majesty and her Prime Minister can never have been less than exhilarating. Then he went and ruined it all by invading Iraq.

Mary Wellesley

Britain has changed irrevocably in the long reign of Elizabeth II, but it also had to reckon with what it once was. In 2011, four elderly Kenyans took the British government to the High Court, seeking reparations for the violence meted out to them during the Mau Mau uprising of 1952-1960. Just before the trial, the government disclosed that it held more than 1,500 files relating to the suppression of the uprising in a secret Foreign Office archive at Hanslope Park. They had been flown out of Kenya in 1963, lest they came into the hands of ‘successor governments’. The Kenyan plaintiffs won their case and, in 2013, the British government admitted that ‘Kenyans were subject to torture and other forms of ill treatment at the hands of the colonial administration’. The 2011 ‘Hanslope Disclosure’ revealed the extent of the violence enacted on behalf of the colonial administration, but also the way in which governments seek to edit history. The word ‘archive’ comes from a Greek word for government; archives are often tools of power. More than 8,000 files, pertaining to 37 former colonies, had been kept hidden. Normally a 30-year embargo is placed on such documents. Elizabeth II had been on the throne for some six decades before the British government was forced to admit the violence it had committed at the inauguration of her reign.

Comments