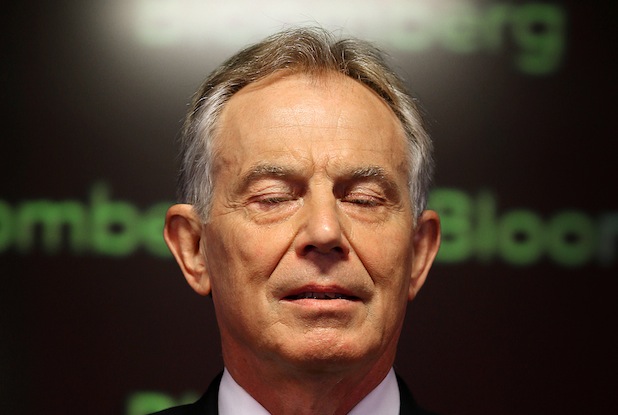

Tony Blair appeared on the Today programme on Tuesday morning to talk about Europe. The televised version showed him against the backdrop of the Brandenburg Gate. He said somewhat predictable things about Ukip being bad and a reformed Europe being good. The mystery was ‘Why?’ Why was he intervening at this point? It took me several hours to puzzle out a possible answer. It lies, I suggest, in his statement that the European project used to be ‘about peace’ and now it is ‘about power’. He was speaking at the beginning of the week when the contest for the presidency of the European Commission comes to a head. Mr Blair emphasised that the socialists in the parliament had done better in the elections than the conservatives. He went out of his way to say nice things about Nick Clegg, thus pleasing the liberals. He knows that the two leading candidates for the presidency are not much favoured, and that nowadays the president can be nominated by the European parliament without support from his own country’s government. ‘The EU needs leadership from someone who understands power,’ was his subliminal message, ‘and just such a person is speaking to you right now.’

Elliot Rodger, who killed six young people and then, seemingly, himself in California at the weekend, said that he had a rough start in life because, when he attended Dorset House prep school in Sussex, he was ‘forced’ to wear knee-high socks. I remember exactly the same experience, and reacting in exactly the opposite way. At my village primary school, the lack of a uniform was a trial to me: it required unwelcome choices and identified children more closely with their background (which, in my case, was uncomfortably more middle-class than most). So when I went to prep school aged nine in the uniform’s knee-length socks, I was delighted. I liked the way the downy hairs on my legs rode over the gartered socks. I liked the feeling the socks gave that one could play football at any time. I felt freer. Obviously poor, deranged Elliot Rodger did not. If you watch the horrifying video he made the day before committing his atrocity, you will see his main motive stated — revenge because no girls would sleep with him although he was ‘the perfect gentleman’. It is almost as if the trauma of compulsory socks led to the trauma of no sex. There is something disturbingly English about this tragedy, although it ended in Isla Vista.

We commentators try to bear our burdens cheerfully, but one of the heavier ones is the danger of having to read whatever new book briefly swims into political fashion. The kinder authors tell you, either in the title or in a phrase, what they are on about, thus saving time. Small is Beautiful or Nudge are examples of the former; ‘the end of history’, ‘the clash of civilisations’, of the latter. Some annoying books, however, don’t really let on, and so we have to read them. The Spirit Level, for example, is an unconvincing account of why equality makes everyone happier which I resent having wasted four hours on. And then came Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century, nearly 700 pages by a left-wing Frenchman who wants the Nobel Prize for Economics. I commented on it briefly in print, and for an uneasy fortnight, it seemed as if I would actually have to read it. But in last Saturday’s FT, an investigation suggested that the statistics cited by Piketty in support of his thesis — that the rich have been getting unprecedentedly richer since 1970 — are flawed. Phew, what a relief! I celebrated by reading Alan Powers’s book about Eric Ravilious instead.

Recently, I have given a couple of talks about Margaret Thatcher in the United States. It is surprising how often different usages of English words make life difficult. In three of the stories I like to tell, the key words are, respectively, ‘torch’, ‘larder’ and ‘cocks’. In the first case, I was aware that the American for torch is ‘flashlight’, but I did not know that the word ‘larder’ is unfamiliar. As for ‘cocks’, well, I learnt from the looks of suppressed dismay/mirth, that the British meaning of ‘male hens’ is, at best, vestigial. The trouble is that the American word ‘rooster’ just cannot be made to come out of the mouth of Mrs Thatcher, so I have had to drop the entire story.

When, in 1976, the Soviet media first called Mrs Thatcher the Iron Lady, which they intended as an insult, they also described her as a ‘Peking plotter’. At that time, the relations between the two great communist powers were terrible. This week, Russia Today, Putin’s English-language mouthpiece, led with the headline ‘Russia-China: A Big Push for Partnership’. The story concerned the new $400 billion deal by which Russia will now supply gas to China. For once, the propaganda emphasis is correct. This deal is probably an even bigger story than Ukraine, and probably even worse news for the West.

Hay Festival became the Glastonbury of literature last weekend. There were such floods that people walked around in wellingtons covered with red Wye Valley mud. Like soldiers in the Great War, you had to stay on the duckboards to avoid sinking. Visitors were made to park at Clyro four miles away and provided with buses to get to the site. Only the ‘artists’ — of whom I was one — were allowed in by car. I have addressed a great many literary festivals in the past year, and so I can compare. Hay remains, in a way, the greatest. The throughput is staggering, so is the range. The overstretched staff are friendly. But Hay is a victim of its own success, bursting at the seams, menaced by clogged roads and irritated inhabitants. One can imagine some dreadful accident — the collapse of the Green Room, say, crushing the flower of English letters. My rustic driver suggested that the whole thing should move to the Royal Welsh Agricultural Society Showground near Builth, although obviously the artists would lower the tone after all those bulls, rams and sheepdogs.

Comments