‘Nice,’ my junior school teacher once surprised the class by announcing, ‘isn’t nice.’ We shouldn’t, Miss Morris went on to explain, describe food as ‘nice’ but instead as ‘tasty’, ‘delicious’ or perhaps ‘tempting’. Similarly, rather than saying that a person is ‘nice’ we should indicate in what way they are nice, describing them for example as ‘charming’, ‘generous’, ‘thoughtful’ or ‘drop dead gorgeous’.

All scatological terms will only score half points (but anyone who adds ‘scato-’ to the front of ‘logical’ obviously deserves bonus)

Well, she didn’t say that last one. In fact, she rather had it in for the word ‘gorgeous’. The nine-year-old me was much miffed when she crossed it out in one of my earliest literary efforts, explaining that it was ‘slightly vulgar’. That still smarts – and after I’d gone through all the trouble of spelling it correctly, too.

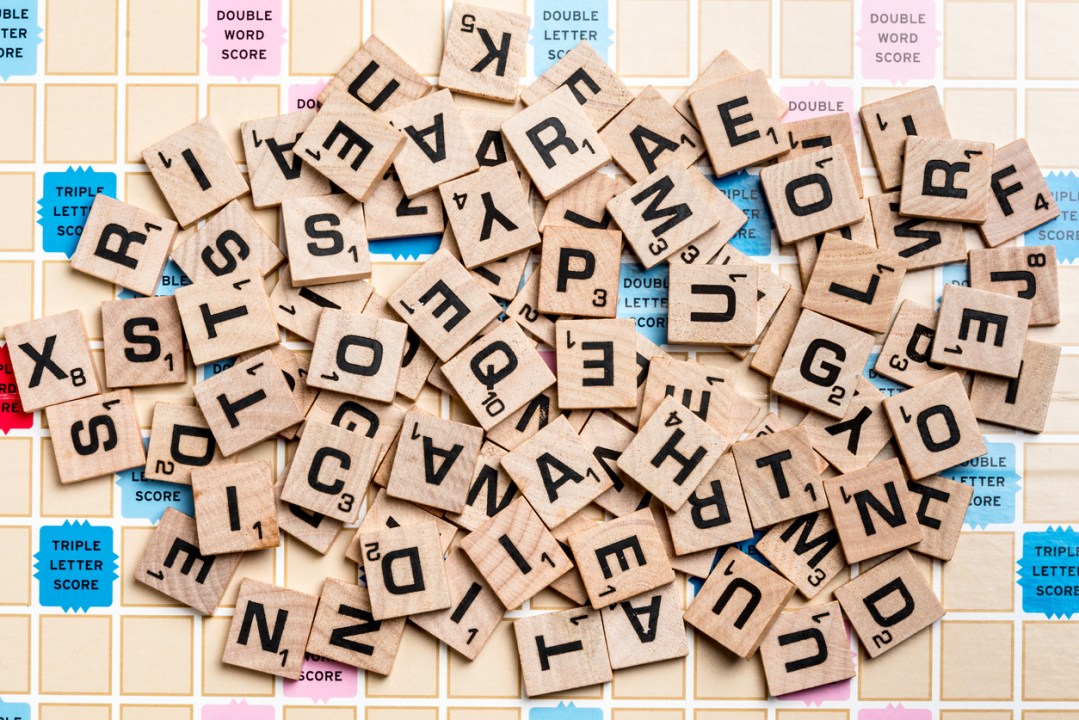

So I can sympathise with the dilemma of Scrabble players who spot that the word which will score them the most points is also a word that in polite society is considered slightly vulgar – or even downright offensive. Imagine, for example, that given the letters on your rack and the state of the board, you realise that the word which would score you the most points is, say, the n-word. You’re not trying to offend anyone; you just want as many points as possible.

You think you could resist the temptation to play it? OK, let’s turn the screw a bit. Imagine it’s a close-run game and you spot that you could play the plural of the ‘n’-word – the ‘n’-word plus an ‘s’. It’s quite a dilemma, isn’t it? Yes, it’s highly offensive, but it’s also most certainly a word – it’s in the dictionary. What’s more, it’ll bag you a 50 point bonus for using all seven of the letters on your rack. But then on the other hand, if you play it… well, it will be on the board for all to see. What to do? Life for the middle classes can be very hard.

Fortunately there may be a simple solution. It requires everyone to accept that all those offensive and derogatory words definitely exist, and that putting them on the board is entirely different from using them in a real-world context. But it also must be accepted that some words simply do cause offence. In Scrabble, as in life, the words we choose matter.

With those thoughts in mind, a minor tweak to the rules seems to be all that is required. You can play such naughty words, but your score will be halved in return for besmirching the board. Of course the great majority of words (‘where’, ‘walk’, ‘window’…) are neutral and so will continue to score as usual. But others, the sort of words that Miss Morris favoured – ‘gossamer’, ‘grace’, ‘saunter’ and ‘lamentable’, for example – should score double. Teams of English teachers could be employed to draw up lists of these high-quality words that deserve double points.

Come to think of it, why stop at doubling? Anyone managing to get ‘petrichor’ (the pleasant aroma accompanying the first rain after a warm dry spell) on the board should have their score quadrupled. The prospect of scoring loads of extra points for classy words like ‘epiphany’, ‘apricity’, ‘nirvana’ and ‘sonder’ (the sudden, profound realisation that each passerby has a life which is as vivid and complex as one’s own) will motivate players and add to the game’s educational appeal.

All scatological terms, of course, will be in the list of words that only score half points (but at the same time anyone who adds ‘scato-’ to the front of ‘logical’ obviously deserves a big bonus). Then there are some words that have several meanings, only one of which is offensive. If you place ‘sod’ on the board you should quickly add, ‘I am referring of course to a piece of turf.’ Similar considerations apply if you play ‘screw’ or ‘hump’.

Scrabble should be a celebration of our language’s rich and colourful vocabulary – there’s no scope for bowdlerising (that’ll be quadruple points, thank you very much). But players have to accept what deep down they’ve always known: that some words are nicer – sorry, are more seemly – than others.

Comments