Kim Leadbeater’s assisted dying bill has generated much talk about the ethics of suicide. As far as the ancients were concerned, it was only in life that you could make your mark. The Christian passion for embracing, even rejoicing at, death made no sense to them.

Ancient thinkers generally did not fear an afterlife. Although there were no received views on the matter (unless you were a member of a cult of some sort), many ancients reckoned that, if the gods were displeased with you, they would demonstrate their hostility in this life rather than the next. But when death was inevitable, they wanted to be in control, because the way one died revealed the true stature of the person, which could do much for one’s posthumous reputation.

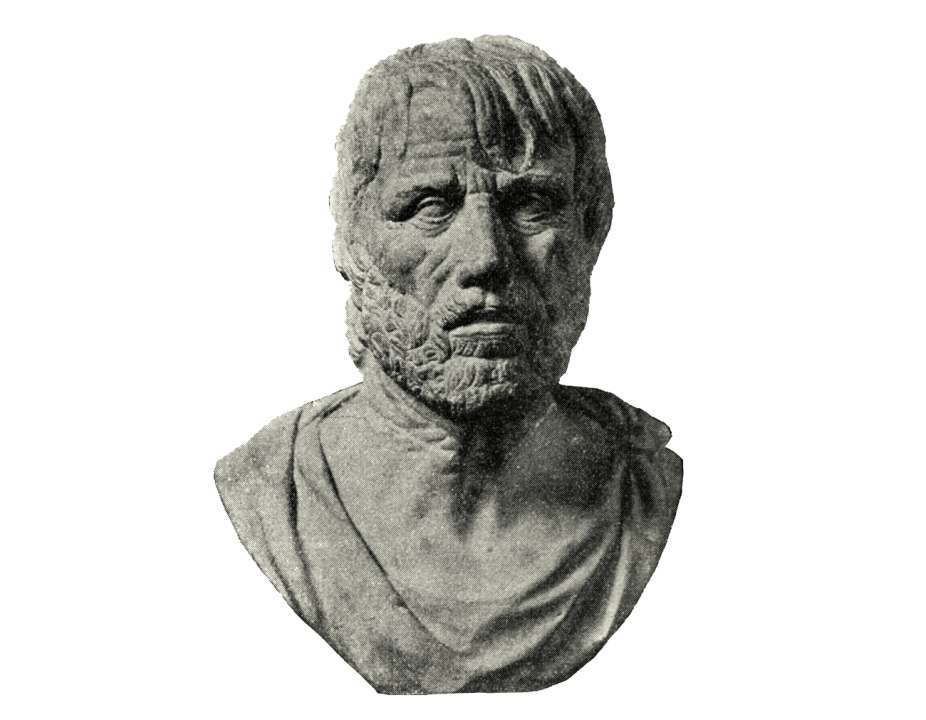

The Roman Seneca, being a Stoic, took the view that, since death, though unwelcome, was no evil, suicide was a rational act. ‘In my opinion, old age is not to be refused any more than it is to be craved,’ he argued. ‘It is very agreeable to enjoy one’s own company as long as possible, on condition that one has ensured it is worth enjoying. The question we have to face is – should we treat extreme old age with disdain and take matters into our own hands, rather than just waiting for it to come?’

Ultimately, the question for Seneca was whether, in living, ‘one is lengthening one’s life or one’s death’; and the danger for him was that ‘one will lose the power to end one’s life in desperate efforts to salvage a portion of it’. He was terrified of the prospect of living into old age, ‘inert and useless and unable to do anything about it. But if old age begins to destroy my mind and pull apart its various faculties, leaving me breathing but not living, I shall immediately evacuate this crumbling and tottering residence’.

Seneca identified a problem as intractable then as it is now, when we can easily prolong a painless life but (in most cases) do little more. But at least Ms Leadbeater is broadly up to pace with Seneca’s latest thinking on the subject.

Comments