By any yardstick, the Norman Conquest was a ghastly business. Within two decades, the English aristocracy had been more than decimated, all of England’s cathedrals were being levelled and rebuilt, the north had been harried and the language of government changed. What made it worse was that it was utterly unnecessary. In 1066, Edward the Confessor had an heir of the blood royal – Edgar Ætheling, the grandson of Edmund Ironside (d. 1016). Had he not been shoved aside by bigger men, much fuss might have been avoided.

In her superbly adroit new history, Eleanor Parker examines how memories of Edgar and his like – the generation that straddled the Conquest – survived, or were melded to meet the needs of the time. For some this meant immortalisation; for others, oblivion. Edgar, surprisingly, has had to settle for the latter. After Hastings, he involved himself with some success in Scottish and Norman politics, fought in the First Crusade, was present at the capture of Antioch in 1098, and was subsequently entertained by both the Greek and German emperors. ‘If any figure from 11th-century English history seemed fitted to become a hero of romance,’ writes Parker, ‘it must be Edgar Ætheling.’

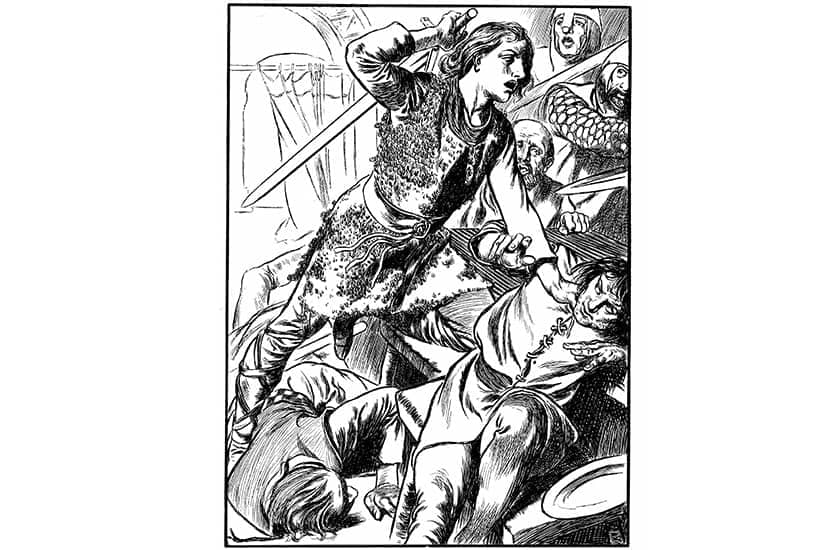

Stories of Hereward the Wake revelled in English strength and ingenuity and were themselves acts of resistance

Why no romantic writer bothered is an excellent question and one Parker is well suited to address. A lecturer in medieval literature at Oxford (and the author of aclerkofoxford, the best medieval blog to be found), she has a facility for weighing stories, authors and their silences. As she shows, to 12th-century Anglo-Norman historians seeking to establish a narrative of continuity across the Conquest, Edgar’s legitimacy was an inconvenient truth. So it was that William of Malmesbury (d. c.1143), whose histories cemented prejudices until the modern period, dismissed him as an anchorless toff. Elsewhere he was airbrushed. The Bayeux Tapestry omits him entirely, and even a book devoted to his sister, the Life of St Margaret, fails to mention him.

After Hastings, Margaret followed Edgar into exile in Scotland, where she married Malcom III (of Macbeth fame) and bore him three Scottish kings and a daughter, Matilda, who would marry Henry I and so unite the English and Norman lines. As part of that project, Matilda commissioned Margaret’s Life which, Parker shows, draws attention to her English royal ancestry by reference to her grandfather Edmund Ironside, but elegantly ignores her father and brother and their claims. The forging of a new Anglo-Norman royalty could not be endangered by the disagreements of yesteryear.

If some sources wrote Englishmen of the Conquest era out of history, others purposefully inked them in. The most feted resister became the proto-Robin Hood figure, Hereward (called ‘the Wake’ since the 15th century, when a family of that name claimed him as one of their own). He was apparently a landowner in the east of England who, having been dispossessed by the Normans, hid in the marshes around Ely and made the invaders’ lives difficult. The tales are rich but the facts few. However, Parker argues compellingly that the Hereward stories, which revelled in English strength and ingenuity, were themselves acts of resistance which helped forms of Englishness to survive in memory, and so persist.

Englishness would also flourish in less likely locations than the Fens. The Godwinsons, Harold’s nephews and nieces, made new lives in Ireland, Denmark, Norway and Belgium, marrying into the royal families of Europe and achieving the status denied them in England. More dramatic still was the departure for Byzantium in the 1070s of a large English group fed up with Norman rule. There they joined the elite Varangian Guard before being granted land in Crimea, where they founded a Nova Anglia complete with a city called ‘Londina’ which survived, with English traditions, until at least the 14th century.

These stories, Parker notes, are known only from foreign accounts. English authors may have become cut off from their protagonists or, just as likely, ‘the silence in Latin and Anglo-Norman 12th-century sources about the fates of the conquered generation… may be a manifestation of trauma’. A reluctance to remember or speak is explicit in the writings of Eadmer of Canterbury, an English monk who, as a boy, had seen both the Conquest and his cathedral burn down:

I do not see why I should write anything about it since those events are so clearly evident without a single word being written that there is no one who could not see the real misery there.

It is much to the credit of Parker’s sensitivity as a scholar that, almost 1,000 years later, she has been able to resurrect, often from silence, the pathos of those decades and the plight of those who endured them.

Comments