As Tory MPs gathered at St Stephen’s entrance in Parliament to await their new leader on Monday afternoon, a choir in Westminster Hall began to sing. The hosannas spoke to the sense of relief among Tory MPs: they had been spared a long and divisive nine-week leadership contest. A period of political blood-letting brutal even by Tory standards was coming to an end. The United Kingdom would have a new Prime Minister.

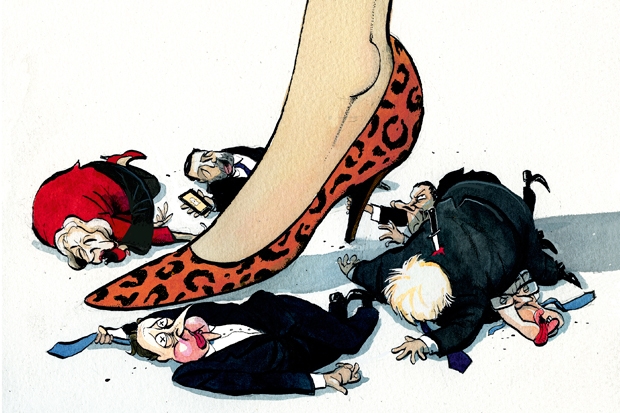

More than relief, there was hope for the bulk of MPs who had previously not been marked out for advancement. Theresa May’s accession shows that the narrow rules which were thought to govern modern British politics are not hard and fast. May is not one of the shiny people. She isn’t a member of a gilded political set. Her success is the triumph of hard grind, perseverance and determination. She kept her head when all about her were losing theirs.

May’s career is very different from Tony Blair’s and David Cameron’s. She was in her forties, not thirties, when she became an MP. Her political experience before Parliament came from being a councillor. It has taken her 19 years from taking her seat in the Commons to reach Downing Street, compared with nine years for Cameron and 14 for Blair. She is also older than both of those men were, not only than when they first entered No. 10, but when they left it too.

‘What a lot of us love is that she is older than us. Everything is possible,’ says one Tory minister who backed her. A cabinet minister told me that May’s arrival marks the end of the fashion for younger, mediafriendly leaders. It is strange to think that David Cameron is leaving Downing Street before he has turned 50.

Theresa May’s new Cabinet

Listen to Isabel Hardman, Fraser Nelson, James Forsyth and Colleen Graffy discuss the PM’s new appointments:

In terms of class, too, May represents a break from Cameron and Blair. It’s true that she went to Oxford, and she is married to another successful Oxford graduate. But she isn’t a member of the Notting Hill set or anything like that. She was a provincial grammar-school girl. Perhaps the biggest difference between her and Cameron and Blair is that she has no gang: there aren’t any Mayites. On Monday night, Tory MPs did not raucously celebrate her elevation in the Commons bars, in the way they might have done if another figure had won.

Rather, they quietly discussed the direction she’ll take the country in; what kind of Brexit she’ll go for; and who will get what job under her. May does have a team of fiercely loyal aides. Her former advisers Nick Timothy, Fiona Hill and Stephen Parkinson all returned to the colours for her leadership bid. They represent another change in style. As one minister observes, ‘Compared to the Cameron people, these people are known to us. We have their phone numbers.’ Interestingly, both Parkinson and Timothy backed Leave in the referendum.

Nobody was sure who May would appoint to which ministerial posts. ‘She doesn’t do likes,’ a cabinet minister told me. As one of her backers put it, ‘This is a meritocracy, or the nearest we’ll get to it.’ May plays her cards close to her chest on most issues, particularly on personnel questions. ‘No one knows what she thinks of people. Not even her junior ministers,’ one minister told me. But she knows. ‘She’s been sitting round the cabinet table for six years, forming judgments on people,’ said another. As Home Secretary, May was a robust voice in cabinet on Home Office and security matters — and she fought her corner when challenged. But she tended not to weigh in on other matters. Cabinet colleagues have little idea of her views on the economy, for instance. Her long-serving parliamentary colleagues don’t know either. Which is surprising, since May started her professional life at the Bank of England and is better qualified than most to opine on the economy. The fact that she did not, since it was not her brief, says much about her.

May is not an ideological politician. She has little time for labels or grand unifying theories. She is driven by a sense of duty. She is often characterised as a cautious politician. But this isn’t quite right. It is true that she likes to approach issues incrementally, but she has been quite bold as Home Secretary. She has taken on the police, for instance, in a way that never happened under Margaret Thatcher. May’s work on the ‘stop and search’ issue sheds intriguing light on her character. Sources say that she took action after hearing from young black Britons who had to deal with being stopped by the police on a regular basis for no good reason. Her ability to understand how that made people feel shows that, for all the talk of her steely character, she is empathic. Those close to her suggest that the police’s misuse of power offended her sense of decency.

That same sense of decency means she’ll have little time for companies and individuals that use morally dubious ruses to avoid paying tax. Those vested interests in the private sector which think no Tory will ever really take them on should look at how May has been prepared to tackle the police as Home Secretary. She’ll also be less interested in courting the Davos elite than many previous occupants of No. 10 have been. It isn’t her style.

May will never be an exciting politician. She wouldn’t want to be. Her childhood hero was Geoffrey Boycott. (One of the Whitehall battles she lost was over an effort to get him a knighthood.) Yet there is, perhaps, a better parallel between her and the current England captain, Alastair Cook. Neither is a swashbuckling player — they don’t empty the bars or make the pundits purr. But both have developed approaches that successfully emphasise their strengths while accepting their limitations.

Arguably, the greatest challenge for May will be doing a job in which she cannot be across the detail on every issue. As Home Secretary, much of her confidence comes from knowing her brief better than anyone. It enables her to hold her own in discussions with colleagues, arguments with her opponents and on the floor of the House of Commons. As Prime Minister, it is not possible to know the details of every question that you must decide. ‘She’s more Brown than Blair, and she’s got to find a way of doing the job that doesn’t drive her mad,’ concedes one of her biggest supporters on the Tory benches.

The other thing that May will not be able to do as Prime Minister is micromanage. As Home Secretary, she has run a tight ship. Those junior ministers who valued autonomy have found her overbearing. In her leadership campaign, May tried to reassure colleagues about her approach. At the second 1922 Committee hustings she emphasised that she would restore proper cabinet government. In meetings with cabinet ministers, she has stressed that she would aim to see them regularly for face-to-face meetings to discuss how to handle issues that concern their departments.

David Cameron promised the same. He said he would restore cabinet government and proper consultation with colleagues. But once in office, he reverted to a more closed system of governing. It remains to be seen whether May really can alter her way of working. One area in which May must give ministers more freedom to manoeuvre is in agreeing new trade deals. One cabinet minister, who campaigned vigorously for Remain, admitted to me this week that he had been taken aback by how many countries were interested in making trade deals with the UK. It is vital that our country is in a position to sign as many of these as it can as fast as possible after leaving the EU. Early deals would create momentum for more and show that Britain was intent on being an open, outward-looking nation. That is one of the keys to making a success of Brexit.

What will Theresa May do between now and the next scheduled general election in 2020? Well, there will be Britain’s exit from the European Union to negotiate. I understand that May has also told colleagues that she still regards the last Tory manifesto as operative, and wants to carry on implementing it. One close ally of hers tells me that we will see ‘accentuations’ to the 2015 agenda rather than wholesale departures from it. But May appears to understand that the defeat for the status quo in the EU referendum was about more than Europe, that too many people feel that the economy doesn’t work for them. The great challenge for postBrexit Britain is to make the country an attractive place for investment while dealing with the unacceptable faces of capitalism.

Another thing confirmed by the EU referendum was the divide between London, which voted heavily to remain, and the bulk of England which voted to leave. Part of this Leave vote was motivated by a sense that their regions were being left behind. In her victory speech to Tory MPs on Monday, May emphasised the need to help parts of the UK that felt this way. If this is to be done, the quality of schooling in these areas will need to be addressed — 28 per cent of pupils in the north-east are going to schools that require improvement. In Blackpool and Doncaster, more than half of all pupils are at failing schools. That entrenches inequality in our country. The Tory party turned to Theresa May because she was seen as offering stability and steadiness in a time of great uncertainty. As the drama of the Tory leadership contest intensified, her cool temperament only became more appealing. But she may well turn out to be an unexpected radical, ushering in changes to the UK that go far beyond Brexit.

Comments