Hugh Jones was 29 when he was killed in action. On Wednesday, the eve of the 80th anniversary of D-Day, his grave at Bayeux – and those of 22,000 Commonwealth war dead in cemeteries across Normandy – was illuminated in a vigil to these silent witnesses to the pity of war.

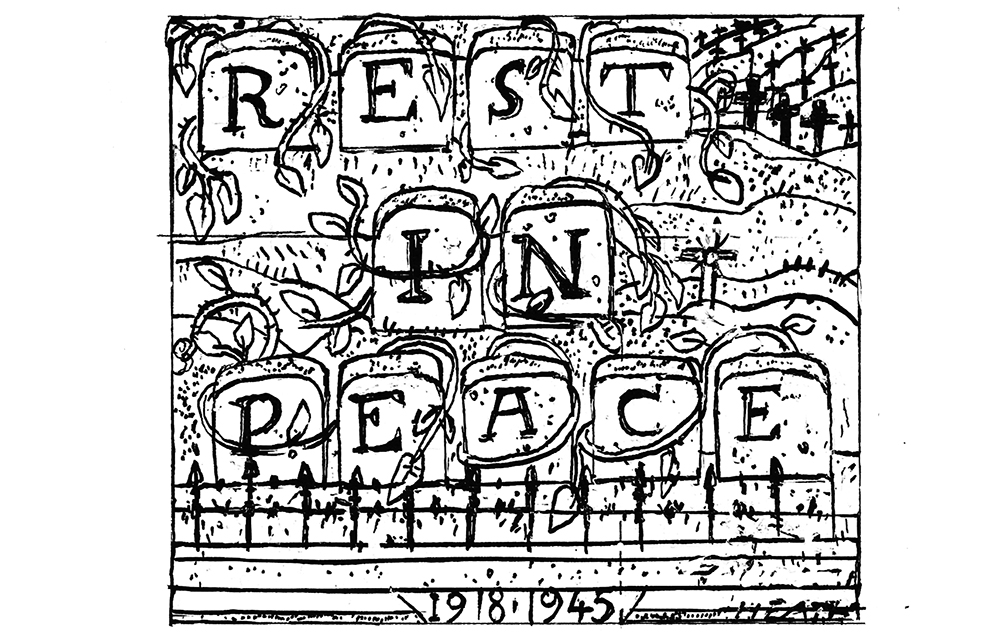

All Commonwealth war cemeteries share a powerful aesthetic. There are more than 2,000 across 134 countries, and in each, lines of soldiers’ graves evoke a battalion on parade. In life, officers and soldiers may have been divided by religion, rank or class but they are unseparated in death. They sit, Kipling wrote, on ‘fair and level ground… Where high and low are one’.

It is difficult to imagine today how revolutionary these cemeteries were when they were built. In previous centuries, our war dead were buried with little ceremony where they fell. But by the early 20th century, funerals had become affordable, so Britons demanded more. As casualties mounted in the Great War, the military historian John Keegan wrote, it was ‘unthinkable that the dead of a national army, dying in their tens of thousands for King, Country and Empire, should be left in hurried graves, marked by some makeshift cross nailed together by comrades’.

How to inter this vast army of the dead? Before the first cemeteries were built in 1920, at Le Treport, Forceville and Louvencourt, four principles were agreed by what was then called the Imperial War Graves Commission: no private memorials, to prevent the wealthy funding more ornate graves; officers and soldiers buried together; no repatriation of remains back home; and every soldier honoured individually. The lack of repatriation and the absence of Christian crosses on graves were particularly controversial, but the cemeteries fast became places of post-war pilgrimage and public concerns faded.

Deciding their design was a difficult task, at times fraught. Edwin Lutyens, one of the four principal architects, wanted a plain ‘war stone’, a kind of altar, at every cemetery. Herbert Baker, one of Lutyens’s oldest friends, preferred a cross, and thought it looked better against the backdrop of the French countryside. At a point, Charles Aitken, a third architect, doubted the project, and thought the budget for the cemeteries should be used for social housing or a university. Baker and Lutyens argued frequently, and Baker wrote in his memoirs that the years he spent designing the war graves became ‘the unhappiest in all my life’s work’.

Still, once the cemeteries were built, that didn’t matter much. After both world wars, bereaved relatives were able to pay for a gravestone inscription of up to 60 characters. In Bayeux, some epitaphs are religious (‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends’); others patriotic (‘His duty nobly done, he died that we might live’). Some are personal (‘In ever loving memory of our dear son and brother’, ‘God Bless our soldier daddy’, ‘My Only Child, he gave his all. Till We Meet Again – Mother’). Some have no inscription.

The mother and widow of Hugh Jones could afford an epitaph for their son and husband. Hugh’s father had been killed at Passchendaele in 1917 and is remembered there. The Jones family knew the grief of war. ‘Not just today but every day in silence I remember,’ Hugh’s grave reads. Our war cemeteries are our greatest preachers of peace.

Comments