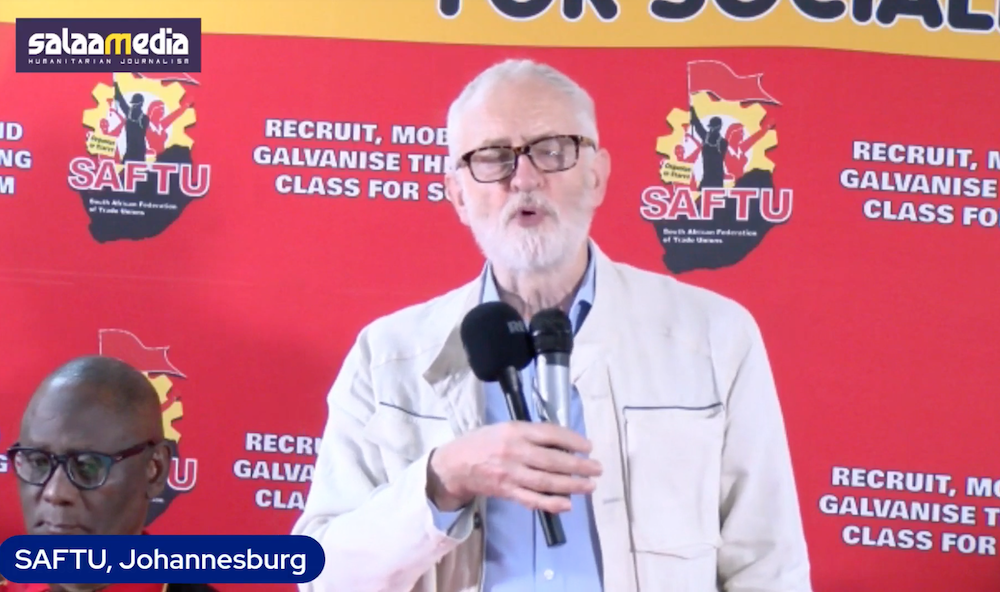

Jeremy Corbyn has spent a lifetime attaching himself to lost causes abroad and failed movements at home. Now, as the still-unnamed ‘Your Party’ continues to tear itself apart, Corbyn quietly slipped away from the domestic drama to South Africa and neighbouring Namibia, where he has been doing what he does best: surrounding himself with trade unionists, pro-Palestinian activists and any podcaster willing to lend him a microphone.

For Corbyn, South Africa has long been a stage on which to project his political fantasies

For Corbyn, South Africa has long been a stage on which to project his political fantasies. In the 1980s he was a fixture of the anti-Apartheid movement and was even arrested outside South Africa House. The charges were dropped, and Corbyn – generous with other people’s money as ever – donated the compensation he received to the ANC. His warmth, however, was not repaid. When his allies begged Mandela to endorse their ‘non-stop picket’ outside the embassy in 1990, they did not even receive the courtesy of a reply.

Still, the romance lingered. The ANC may have gone from liberation movement to ruling kleptocracy, but Corbyn has kept the faith. The country’s trajectory since 1994 – from the euphoria of Mandela to corruption, rolling blackouts and economic collapse – is something he dutifully acknowledges in passing before quickly changing the subject. What really impresses him, he said recently on a podcast, is that the ANC dragged Israel to the International Court of Justice on charges of genocide.

That ICJ case is not universally popular in South Africa. This is a majority-Christian nation, and many of its largest churches are strongly orientated towards Israel. The case was brought in the run-up to elections, and its timing coincided suspiciously with the ANC’s sudden escape from bankruptcy. Allegations that the case was encouraged by Iranian bribes swirl around.

Still, Corbyn is presumably unaware of this. Instead he spent his time in South Africa catching up with this old comrades. At one recent event he was photographed arm-in-arm with Ronnie Kasrils, a former ANC militant and intelligence chief. Kasrils is not some faintly embarrassing has-been of the revolution. He is a man who, shortly after the Hamas atrocities of October 7th, called it ‘a brilliant, spectacular guerilla warfare attack… They swept on them and they killed them and damn good. I was so pleased and people who support resistance applauded.’ Kasrils subsequently said he was only talking about attacks on the military on 7 October and the ‘second phase of what happened’ couldn’t be supported – yet his glee about at least the initial operation was obvious.

Jeremy Corbyn this week called Kasrils a ‘fantastic comrade’, describing him as ‘an example to all of us.’ Nothing more really needs to be said. The image of Corbyn, praising a man who applauds the murder of Israelis, is indictment enough. It was not a slip. It is who Corbyn is.

South Africa itself is the perfect backdrop for Corbyn. It flatters not just his sentimental nostalgia, but his entire political philosophy. Every radical left idea has been tried here, and the results are on daily display.

The state owns vast sectors of the economy. The national airline went bankrupt. The once-mighty railways are in ruins. The electricity grid sputters along with rolling blackouts, flickering on and off like a candle in the wind.

The armed forces, once among the most formidable in Africa, are left with only six functioning aircraft – down from 300. Corbyn – who spent his career arguing that Britain should disarm itself in the face of every conceivable threat – might think this a pacifist triumph. In truth, it is not the victory of peace but the result of decay and incompetence.

And then there is welfare. South Africa already operates something resembling an improvised Universal Basic Income – not in name, but in effect. Seven and a half million taxpayers support 28 million grant recipients. The numbers do not add up – they never do. Yet this is precisely the arithmetic of Corbynism: a system where the productive minority is endlessly squeezed to fund an ever-growing dependent majority, until neither group can stand.

None of this seems to bother Corbyn. Just as he peers at Havana’s crumbling streets and sees ‘social justice’ or at Caracas’s breadlines and sees ‘democratic socialism’, so too he gazes at Johannesburg’s blackouts and Pretoria’s corruption and sees not a warning but a model. What others recognise as failure, he wants to replicate in Britain.

So what is Jeremy Corbyn doing in South Africa? The same thing he has always done: embracing failure, romanticising collapse and applauding men who cheer on murder.

Comments