When Portuguese traders sailed past a verdant, mountainous land on the fringe of the Chinese empire in the mid-16th century, they named it Ihla Formosa – ‘beautiful island’. But Kangxi, the third emperor of the Manchu Qing Dynasty, was less impressed when his naval forces captured it in 1683, scoffing: ‘Taiwan is no bigger than a ball of mud. We gain nothing by possessing it, and it would be no loss if we did not acquire it.’ Beautiful or not, Taiwan was a pirates’ lair, inhabited by tattooed head-hunters and best left alone.

Yet the Qing clung on to Taiwan for two centuries, with Chinese settlers gradually displacing the indigenous Austronesian population. In 1895, the island was ceded under the Treaty of Shimonoseki to Japan, which transformed it into a model colony with good sanitation, modern railways and a formal education system. When Japan surrendered to the Allies in 1945, Taiwan was occupied by the nationalist troops of Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China (ROC). Then, in 1949, when the victorious communists founded the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Chiang evacuated across the Taiwan Strait. To this day, Taiwan is officially the ROC.

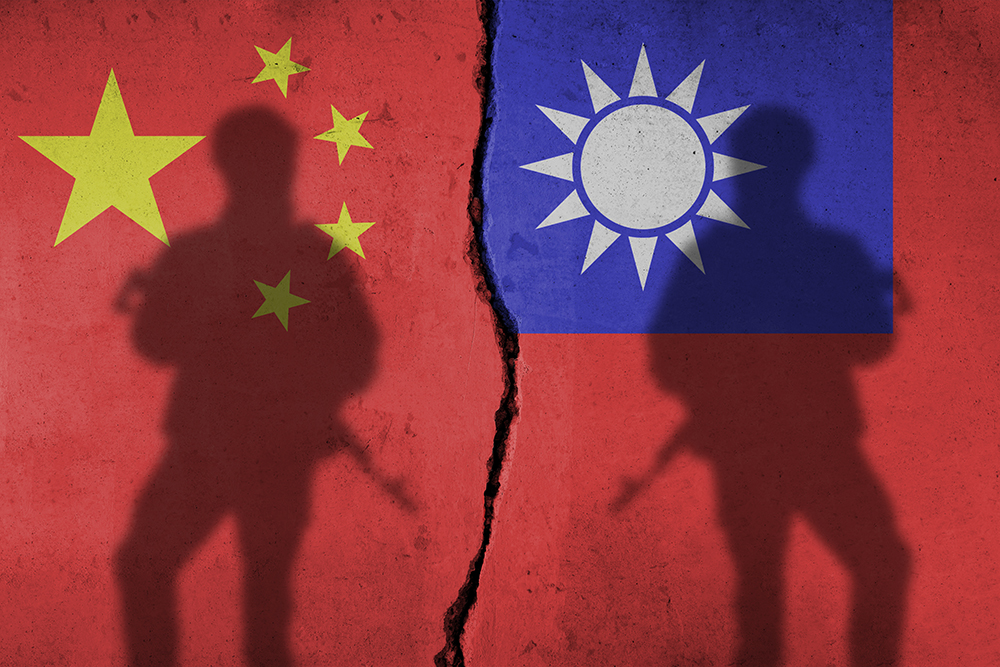

Contrary to the PRC’s claims, Taiwan has not always been part of Chinese territory. But whether the 22 million ethnically Han Chinese who live there today are Chinese, Taiwanese or a mixture of the two is a complex and highly contested question. For Xi Jinping, however, it is straightforward. ‘Blood is thicker than water, and people on both sides of the Strait are connected by blood,’ he declared last year. For Chris Horton, the author of Ghost Nation and a veteran reporter who has lived in Taiwan for a decade, it is equally simple: Taiwan is not Chinese.

In a punchy narrative, he sets out to ‘dispel the carefully crafted disinformation sowed by Beijing’. His intention is to provide Taiwan’s friends and protectors with a better understanding of its people, history and politics. His book is the result of hundreds of interviews, including one with the aged Lee Teng-hui, the ‘father of Taiwan’s democracy’, conducted shortly before his death in 2020. Horton dips into geopolitics, explaining the strategic rationale for China to take Taiwan. But Ghost Nation is at heart a journalistic history of Taiwan’s long march to become ‘Asia’s freest country’, not a war-gaming analysis to rival the think tanks in DC.

Horton is especially good on the brutality of Chiang Kai-shek’s quasi-fascist Kuomintang (KMT) regime, which ruled Taiwan under martial law from 1949 to 1987. From day one it behaved like an occupying force, seizing land and plundering the island. An estimated 28,000 people died during ‘228’massacres in 1947 – the KMT’s ‘original sin’. Around two million nationalist refugees crossed the Taiwan Strait in 1948-50, adding to the existing population of approximately six million. The native Taiwanese were kept in check during the 38 years known as the White Terror, when Taiwan became a surveillance state, subject to strict indoctrination and brutal punishments. Political prisoners had sharp sticks rammed up their backsides or were forced to eat dog shit.

With the end of military rule in 1987, Taiwan began the slow, difficult process of democratisation. In 2000, Chen Shui-bian of the Democratic Progressive party (DPP) became the first non-KMT president in the ROC’s 55-year history. After eight years of Ma Ying-jeou’s KMT government from 2008, which forged closer ties with China, the DPP returned to power under Tsai Ing-wen in 2016. Last year, she was succeeded by the DPP’s Lai Ching-te, who is reviled in Beijing for describing himself as ‘a pragmatic worker for Taiwan independence’. DPP governments have delivered social liberalisation – Taiwan became the first country in Asia to make same-sex marriage legal in 2019 – and fostered a strong sense of Taiwanese identity.

Herein lies the problem with Horton’s account. It is written entirely with a pro-independence view, hammering home the point that the KMT (and CCP) are illegitimate rulers. If so, why did a third of Taiwanese vote for the KMT in last year’s election, and why does it currently dominate Taiwan’s parliament? Horton is scathing of the KMT’s ‘ethnonationalism’, but he does not acknowledge that many Taiwanese view today’s DPP itself as a nationalist propaganda machine. I laughed out loud when he lambasted media organisations that decline to call Taiwan ‘a country’ for betraying the ‘fundamental principles of objectivity in journalism’. At times his own narrative amounts to an erudite rant. This is fine for readers who understand Taiwan’s deeply polarised politics, but it is hardly the ‘panoramic view’ promised on the dust jacket.

So what next for the beautiful island? Horton warns that China is quickly closing the military gap with the US, building the forces it needs to invade. A giant amphibious assault carrier ferrying robotic attack dogs could come into service by the end of next year. Xi has allegedly told the People’s Liberation Army that it must be ready to attack Taiwan by 2027 – though capability does not necessarily entail intent. A war in Taiwan, which sits on the world’s busiest shipping route and manufactures 90 per cent of its most advanced semiconductors, would cause a global depression. But does Donald Trump care about Taiwan beyond its use as a bargaining chip with Beijing? We may be about to find out.

Comments