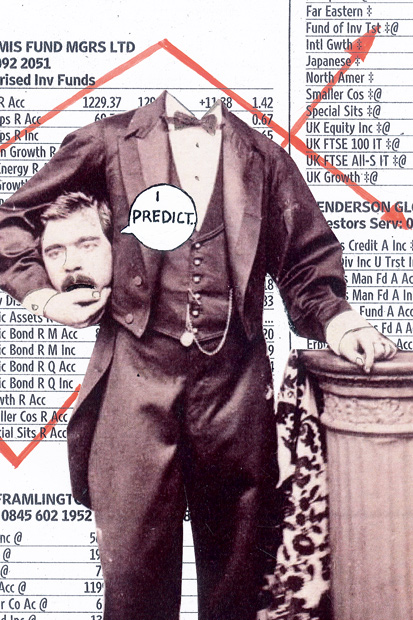

I have a confession to make. I earn my living advising my readers whether particular companies’ shares are going to go up or down. I have no idea whether an individual share will go up or down. Fortunately, nor does anyone else.

That goes for the analysts, investment bankers, fund managers, accountants and other professionals who work in the City and earn a great deal more than I do. As the scriptwriter William Goldman said, no one knows anything.

My abject failure to predict the future has two consequences. One: I am sitting here typing this, rather than being on a beach somewhere, counting my yachts. Two: the best I can do is get it right more often than not, and when the tide runs in my favour, point it out as often and as loudly as possible.

Last year was an excellent one. The clutch of ten investments I suggested my readers bought rose, on average, by 55 per cent or so, I reported at the end of it. (Actually, it rose by 57 per cent, a kind reader pointed out subsequently. I had forgotten a special dividend on one of my smaller investments. I can’t even get it right when I get it right.)

An increase of 55 per cent, if achieved by a fund manager, would be cause to send off for yacht catalogues. One of my investments, in Thomas Cook, was up by more than 200 per cent. This was not down to any great insight on my part; Cook had got itself into awful trouble, spending a fortune expanding onto the high street just as people were buying their holidays online. It appointed a very tough new chief executive, Harriet Green, whom I knew from when she ran a rather dull electronics distributor called Premier Farnell. I took the view that if anyone could do it, she could. I never thought the shares would do quite so well.

The other nine did well enough, in some cases very well indeed. Save one. This was the one suggested to me by a Very Senior Personage Indeed at the Times, though I take all responsibility for the choice. No one knows anything, remember.

I made ten more selections for this year at the start of January. So far, and we have not yet completed the first quarter’s trading, three of them have issued unexpected profit warnings.

As it happens, I believe that of my three failed tips this year, two at least will come good. One is Rolls-Royce, a staggeringly strong company, one of the UK’s best, with an order book of £60 billion or so stretching forward many years.

The other was Centrica, owner of British Gas, to which you probably pay your bills, but with huge oil and gas assets off Brazil and east Africa. After a series of upsets last year, management had assured me, and anyone else prepared to listen, with tears in their eyes that all the bad news was out of the way. It wasn’t.

The third of my dogs was Royal Bank of Scotland, a minuscule proportion of which I own. As do you, through the state’s 83 per cent holding. I took it personally, therefore, when the bank came out with excuses. This one, too, should recover. I chose RBS because banks are heavily exposed to the UK economy, which is clearly on an upwards trend. The more money you, I and businesses have, the more the banks can extract from us all.

I have been doing this job for almost four years and I have only had one complaint against me personally. A very mild email came in saying I had advocated a buy of some misbegotten hi-tech stock, which had promptly collapsed. Would I advise his hanging on for a recovery, or should he cut his losses?

My reply was twofold. One: I am not allowed to give individual advice. I don’t have the qualifications. Two: never heard of the company. Are you sure I told you to buy the shares? Actually, I checked and I hadn’t. It was a colleague filling in for me when I was on holiday.

I will give you one piece of advice, and this is serious. If you have been investing in stocks and shares over the past couple of years, you have been playing the market with loaded dice. This time, though, the dice have been loaded in your favour.

For the past five years or more, governments in this country, the US and elsewhere have been indulging in a massive financial experiment. It goes by the name of quantitative easing because this is seen as more politically acceptable than calling it printing money. Or stealing from savers and pensioners.

The governments have been buying bonds as a way of injecting money into their economies. Bonds are instruments that pay a fixed income as a percentage of their face value. Governments buying them increases their value. This reduces the income holders get when they, too, buy them. If their tradeable value rises, you have to pay more to get at that income.

As the income from those bonds has fallen, investors seeking a return have turned to other assets, in particular shares in quoted companies. And this has pushed up the value of those shares. Logically, therefore, when quantitative easing ends, shares should fall. Almost a year ago the market got a fit of the terrors when Ben Bernanke, then chairman of the Federal Reserve, the US central bank, stated the blindingly obvious: that quantitative easing would indeed end at some point. Prices tumbled, especially on markets in emerging economies. The question no one knows the answer to is how much of that potential fall is already included in share prices at their current level. It is one reason to remain nervous over equities, in my view.

There are plenty of others. The markets seem to suffer from crisis fatigue — they can only focus on one at any time. At present it is Ukraine. But there are other known unknowns. The euro crisis, which has not gone away, the deadlock over the budget in Washington. China, both its economy and military ambitions.

For someone like me who has been watching the market since, ooh, about the South Sea Bubble, there are plenty of reasons to indicate that prices are a bit toppy. We have seen several companies gaining quotes on massive valuations that have not quite got around to the boring business of making a profit. Last time that happened, the dotcom boom of the late 1990s, was just before the last market collapse.

Shares are trading at levels that pre-suppose nothing can go wrong. Professionals like me look at price-earnings ratios. This is a way of correlating share prices to how much the companies actually make. There are any number of perfectly respectable, well-run companies on multiples of 16, 17, 18. This means the market expects profits to remain at their current levels for 16, 17, or 18 years.

This looks a little optimistic. Companies do not disappear in a puff of smoke, unless there has been actual fraud committed. But they do dwindle and die if there are fundamental, unforeseen changes to the markets they serve. Look at the damage Amazon has done to HMV and the like. Somewhere out there are other disruptive technologies, unknown unknowns.

Yachts again. There is an old, apocryphal story of the boss of a successful fund manager showing a guest around and pointing to the marina outside his window. Look at all those yachts, he said. They are all owned by my staff, paid for out of their bonuses. But where, asked the guest, are the clients’ yachts?

Some think the investment community has bought far too many yachts over the past few years, while failing to enrich the people whose funds it looks after. I would tend to agree. But I like to think some readers, if they have taken my advice, might have been able to afford the odd skiff.

Comments