Exhibitions are only as good as the loans that can be secured for them, as was seen at the Royal Academy’s Manet exhibition recently. The exhibits at Burlington House were thin on the ground because in some cases promised loans were rescinded, and other items were simply not available. Whatever one thinks of that controversial figure Norman Rosenthal, for so many years exhibitions secretary at the RA, his ability to seek out and obtain loans amounted to genius, backed by two important characteristics: audacity and tenacity. When I first saw the Courtauld’s Picasso show, I immediately thought of a painting of the artist’s friend Casagemas on his deathbed, lit by a flickering candle. An intense and memorable image, it was painted in the period surveyed by this exhibition, and should, ideally, be on the walls at Somerset House. The fact that it’s not there has less to do with the wishes of the show’s curator, Dr Barnaby Wright, and more with the fact that the painting’s owner, the Picasso Museum in Paris, is currently closed and has sent its collection off on tour to raise revenue. Even the most assiduous curator can’t compete with a prior (and money-spinning) commitment of that sort.

But the painting I remembered so clearly is not really missed in this excellent exhibition, which has been so well selected that nearly every picture is a winner. I like the small concentrated shows at the Courtauld: they allow for a real sense of focus and commitment without exhausting the visitor, and the Picasso show is another of its hits. The theme is 1901, the year the 19-year-old Picasso reached an early artistic maturity and started to sign his work with that distinctive signature. He had already visited Paris, before returning to Madrid, and it was while he was still in Spain that his close friend Carles Casagemas shot himself on 17 February. Picasso was much affected by this act (perhaps he felt guilty at leaving his unstable friend behind in Paris?), and admitted later that it was thinking about Casagemas’ suicide that started him painting in blue. The Courtauld’s show is built around the El Greco-like ‘Evocation (The Burial of Casagemas)’, which is hung on the end wall of the main gallery like a secular altarpiece, with a painting of ‘Casagemas in his Coffin’ to the left. The tragedy certainly left its mark: it gave us Picasso’s Blue Period.

The first room is full of pictures of difficult subjects, exuberantly painted. When he returned to Paris in May 1901, Picasso had just over a month to produce enough work for his debut show with Ambroise Vollard, one of the most influential dealers in the city. He painted with passion and fury, finishing as many as three canvases a day and sleeping very little. Inevitably he drew upon all the inspiration available to him, reprising and interpreting pictures he’d admired by the likes of van Gogh, Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec. ‘Spanish Dancer’ is almost Klimtian in its gold and blue background patterning, while the vivid kaleidoscopic colour and leaping brushmarks of ‘Dwarf-Dancer’ transcend its Lautrec-like model. As John Richardson writes, ‘They are the first manifestations of the combination of compassion and grotesquerie, and the notion of conventional beauty as a sham, that Picasso derived from Goya.’

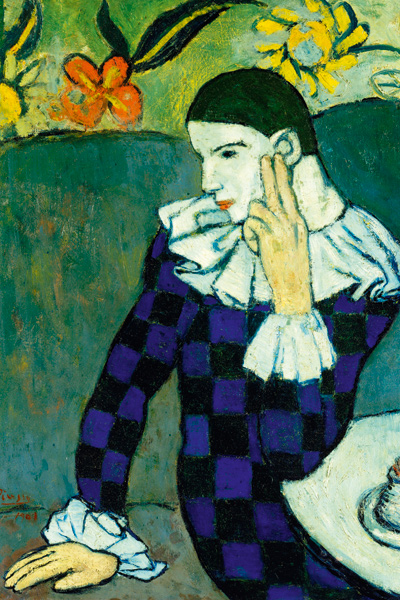

The main room moves away from these theatrical tours-de-force, and shifts gear in subject and mood. Here are the Casagemas pictures, the Harlequin paintings and ‘Absinthe Drinker’: note the long, etiolated fingers, the curled and isolating postures and the pervading melancholy. Sinuous black outlines emphasise a compelling clarity of design, and a couple of potent self-portraits, the first more dashing than the second, chart the artist’s developing introspection. These are paintings to think about, not just look at.

A supplementary display, entitled Picasso, Matisse and Maillol: The Female Model, can be found through the room of Kandinskys and Jawlenskys behind Becoming Picasso. Rather an enjoyable group of works, it begins with an exquisite sanguine lithograph by Maillol of a nude seen from the rear with her arm raised. Picasso is represented by his famous ‘Drinking Minotaur’ etching and a ‘Reclining Woman’, while Matisse figures plentifully — with the very direct transfer lithograph of ‘Thoughtful Figure in a Folding Chair’ and ‘Standing Nude with Cropped Head’. A couple of delicious Maillol drawings and an etching of a crouching woman reiterate the relaxed and sensuous qualities of his line. There’s no space to mention any of the other treasures of the Courtauld, which provide such a unique context for the Picasso show — the beautiful and arresting paintings by Degas, Matisse, Derain et al. The Picasso exhibition can and should absorb the viewer utterly. Concentrate on it, revel in it, and perhaps return another day to sample the Courtauld’s permanent collection.

The Critic’s Choice currently at Browse & Darby is my own selection of postwar British painting, covering the period 1950–2000. With much effort and not a little disappointment at things unobtainable, I have narrowed down my choice to 27 artists, ranging from Norman Adams to William Scott. Many of the exhibits are what is commonly called abstract, yet most derive ultimately from things seen and are only remade according to the instincts and skills of the artist concerned. In the end, there is very little difference between abstract and figurative art but many different ways of painting a picture, and I have chosen good examples from a wide range of interpretations intended to demonstrate the richness of British painting in the second half of the 20th century. Although some of the artists I’ve selected are known to the public and a couple have museum exhibitions running as I write (Scott and Kitaj), most are to a greater or lesser degree neglected by the art establishment. Our public galleries have a duty to show the variety of art produced in this country, yet the painting of the past 60 or 70 years is not currently fashionable with curators, so it doesn’t get exhibited much. Commercial galleries must step into the breach and I’m proud to be associated with this survey show at Browse & Darby: it may be small but it’s as beautifully formed as we could make it. Come and see for yourself.

Comments