Should we be pleased that net government borrowing for June came in below expectations, at £22.8 billion – £5.5 billion less than June 2020? Should we see it as a sign that the economy is recovering a little faster than had been hoped? That is the spin being put on the public borrowing figures released this morning. An alternative, and less rosy, view might come from examining two figures in particular. Firstly, while borrowing is down compared with June 2020, public spending is actually up. Over the month the government spent £84.1 billion of our money, £2.5 billion more than in the same month a year earlier.

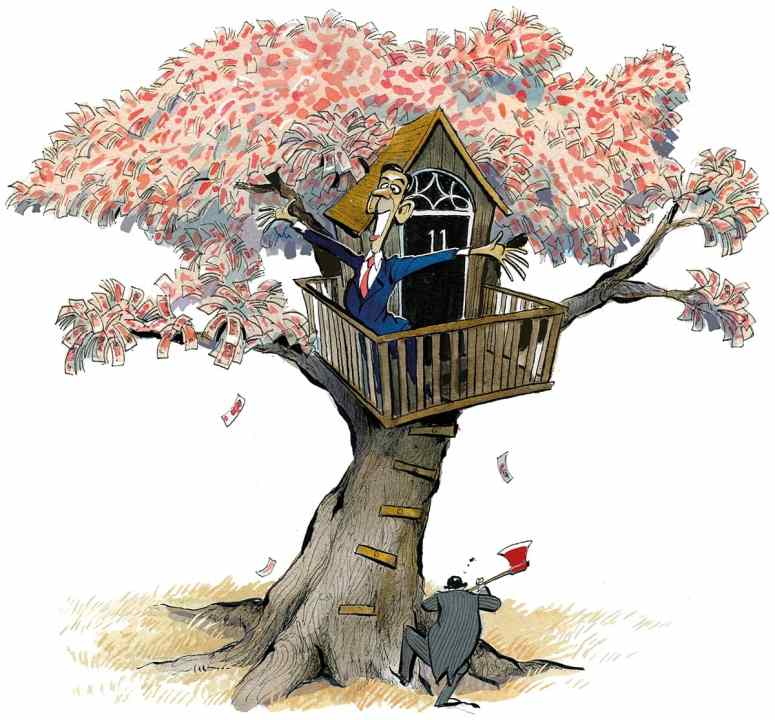

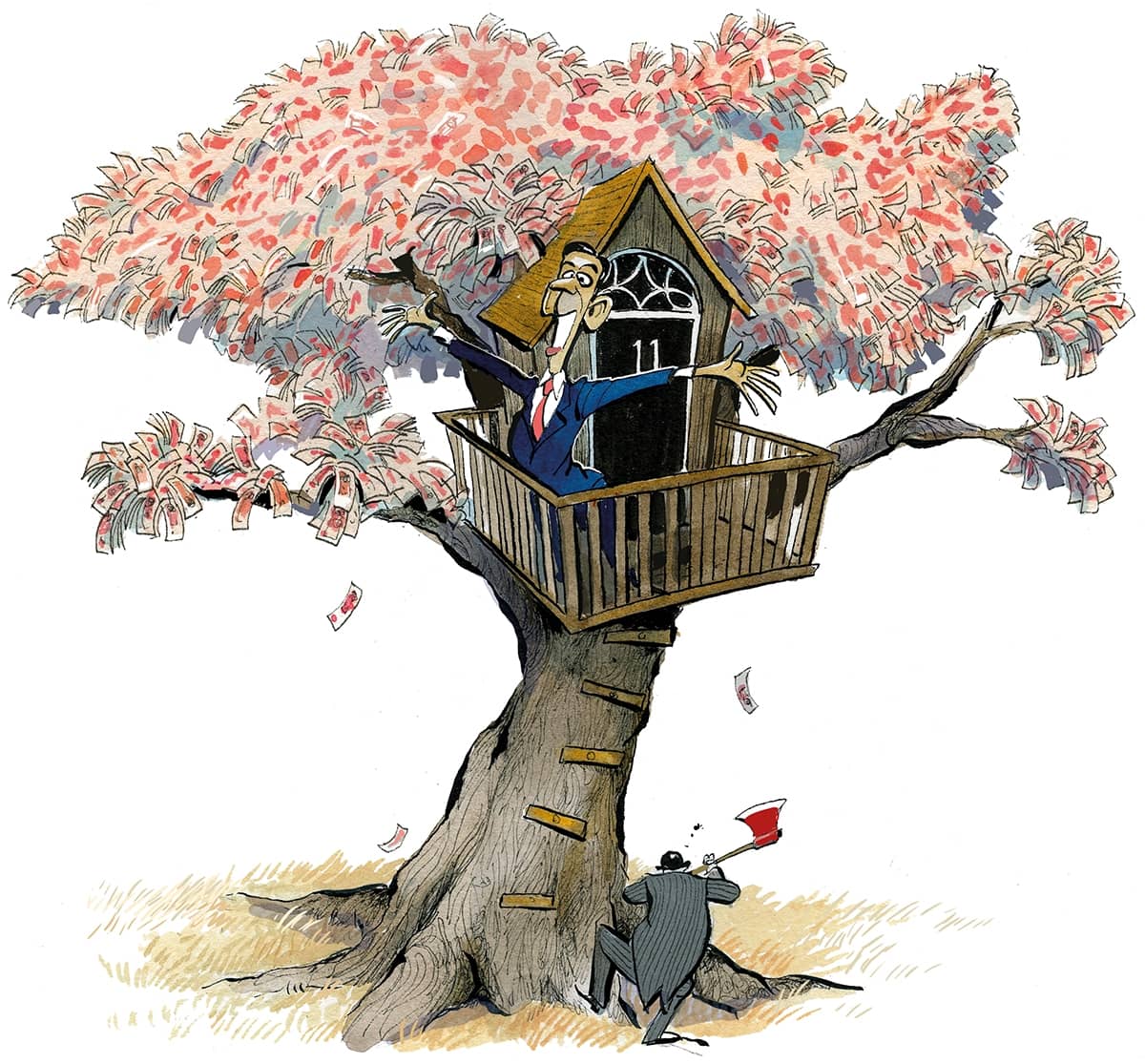

Balancing the budget seems to have become a deeply unfashionable debate in UK politics

That is extraordinary. In June 2020, we were still very much in the depths of lockdown. Non-essential shops were not allowed to open until 15 June; hospitality was not allowed to open its doors until July. The call on the horrendously expensive furlough scheme was still close to its peak.

This June, all shops were allowed to open throughout the month, as were all bars, restaurants and hotels. Far more people were in productive work. Yet even so, the government managed to spend more money than it had in the full emergency conditions which existed a year earlier.

If the government cannot cut its expenditure as the economy and society are allowed to reopen, when is it going to reduce these emergency levels of spending? Does it have any intention of doing so, or does it now see the emergency levels of spending in the spring of 2020 as ‘normal’?

The second figure which ought to set alarm bells ringing is for figure for debt interest payments, which reached £8.7 billion – more than a tenth of overall government expenditure. If the government is spending 10 per cent of its income servicing debt when the Bank of England’s base rate is at 0.1 per cent, how quickly could the cost of repayments run out of hand when interest rates rise?

While interest payments won’t rise immediately in line with interest rates because a lot of government debt is on long-dated gilts and the like, rising interest rates would nevertheless lead to a rapid-worsening of the borrowing figures – the government would be forced to borrow to pay its interest bill, in the manner of a compulsive spender forced to juggle credit cards in order to keep afloat. Either that, or we head further down the road of printing money – and the hyper-inflation that is likely to cause.

Balancing the budget seems to have become a deeply unfashionable debate in UK politics. The determination with which the coalition set about rebuilding the public finances a decade ago has vanished. We may soon come to regret that.

Comments