Who is Keir Starmer, and what does ‘Starmerism’ stand for? Well into his second year as Labour leader and most Britons remain unsure. It’s not as if Starmer hasn’t spent a lot of time and effort – and so many words – in trying to define himself: he was even interviewed by Piers Morgan for an hour on ITV to highlight his human side.

But something has gone wrong. Is it the message or the messenger? Or is the difficult Covid-dominated times in which he became leader that is to blame? Whatever the reason for Starmer’s curiously forgettable leadership, it is now imperative that Starmer starts to make a clear and positive impression on voters: he needs to be more than ‘Not Jeremy Corbyn’.

If he is to do this, Starmer has to transcend a factionalised party and a divided country, something which he has so far failed to do with sufficient vigour: too often, instead of imposing himself on events, events have appeared to impose themselves on him.

Starmer was elected Labour leader promising to unite a factionalised party. On that basis he won the support of all of Corbyn’s most implacable opponents as well as a significant number of those who still regarded the outgoing Labour leader positively.

Starmer needs to be more than ‘Not Jeremy Corbyn’

Since then, Corbynite irredentists have forced his hand to take action against them. Often this has been over their refusal to take seriously the need to adhere to the stipulations of the Equalities and Human Rights Commission’s investigation into anti-Semitism. But while there are Labour members who believe Starmer is a ‘Tory Lite’, and Corbyn’s own future as Labour MP hangs in the balance, the party is the least of his problems. An opinion poll lead such as the one Starmer enjoyed during 2020 would silence most critics.

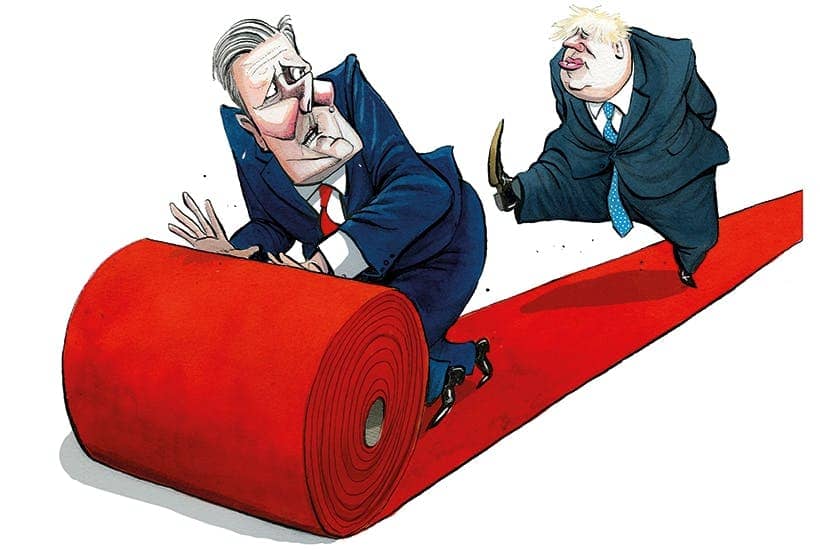

When he was campaigning to become leader, Starmer promised to make Labour more electable: it was this that drew former Corbyn supporters into the Starmer camp. But since the roll out of the Johnson government’s vaccination programme the Conservative party has enjoyed a consistent and at times huge poll lead. The Tories even managed to take the Hartlepool constituency from Labour in the May by-election. And despite the uproar about the Tory tax hike to pay for social care, this is unlikely to be enough on its own to woo those who backed Johnson at the last election to vote for Starmer.

So what’s going wrong? For one thing, Starmer has not yet solved the electoral problem which also foxed his two immediate predecessors. If he wants to be prime minister, Starmer has to win back Leave-supporting red wall seats that have been drifting away from the party across the last three general elections. But even should he do that, it would still be insufficient.

Why? Because Starmer also has to hold on to those younger and university educated metropolitan voters increasingly drawn to the party since 2015 and very much in favour of Remain. An electorate divided along these generational and educational lines has been very much in the Conservative interest: pitching these two groups against each other helped Johnson win his 80-seat majority in 2019. But Starmer has to find ways of appealing to them both.

Such long-standing electoral shifts are the result of deep-set demographic trends. But the right vision, the correct policies and an effective leader who can persuasively articulate a shared, common interest, one embodied by himself and his party can still help Labour back into power. But, clearly, Starmer has yet to find the right approach; and the question that increasingly hangs over him is: will he ever?

The good news for Starmer is that at the end of September his set-piece speech to the Labour party annual conference gives him an invaluable chance to address this question. Unlike last year, when he spoke to a camera in an empty room, the conference hall in Brighton will be full of (hopefully) cheering members. In preparing for this critical moment, he will know that there are basically two models of conference speech available to a Labour leader: helpfully, both have been suggested to Starmer by supporters and critics in recent weeks.

There is the ‘leader vs party’ speech designed to highlight the leader’s principles and willingness to apply them even if it means taking on their own members. The first of the two most famous examples of this kind of address came in 1960 when Hugh Gaitskell rejected a conference vote in support of unilateral nuclear disarmament, declaring that he and his supporters would ‘fight, and fight, and fight again, to save the party we love’ from extremists. Twenty-five years later Neil Kinnock used his conference speech to attack the Trotskyite group Militant Tendency which had taken over the Labour-run Liverpool Council with disastrous results for the city.

In contrast there is the ‘Leader as Visionary’ speech. The most well-known instance of this kind of oration was given by Harold Wilson in 1963 when he declared he wanted to build a ‘new Britain’ through unleashing the ‘white heat’ of the ‘scientific revolution’, something only his party had the capacity to accomplish. Similarly, Tony Blair in 1994 outlined the need not just for a New Labour but for a New Britain, both of which could be achieved under his leadership.

One speech looks inwards and the other outwards; one highlights internal division, while the other associates the party with a shared vision of a nation in desperate need of change. Although there are some in the party who believe the menace of Corbynism remains and needs to be completely purged from its ranks, it is more than likely that Starmer will opt for the latter speech. Indeed, he has tried such a speech on various occasions this year – if to little effect. Hopefully, for him, practice makes perfect, for he will get few more chances in the future.

But a speech is just a speech. Wilson and Blair each spoke after over a decade of Conservative governments, both of which were seemingly drawing to a whimpering, contemptible end. The Conservatives today have now been in office for a similar period but have somehow managed to renew themselves such that Johnson’s government still feels new. But perhaps as ministers struggle to agree how to Build Back Better after Covid, and try to manage their own problem of keeping their red and blue wall seats happy, they will give Starmer his opportunity to outline his version of a unified and reformed New Britain?

To do that, however, he has to be more than ‘Not Boris Johnson’: he has to show us who is Keir Starmer.

Comments