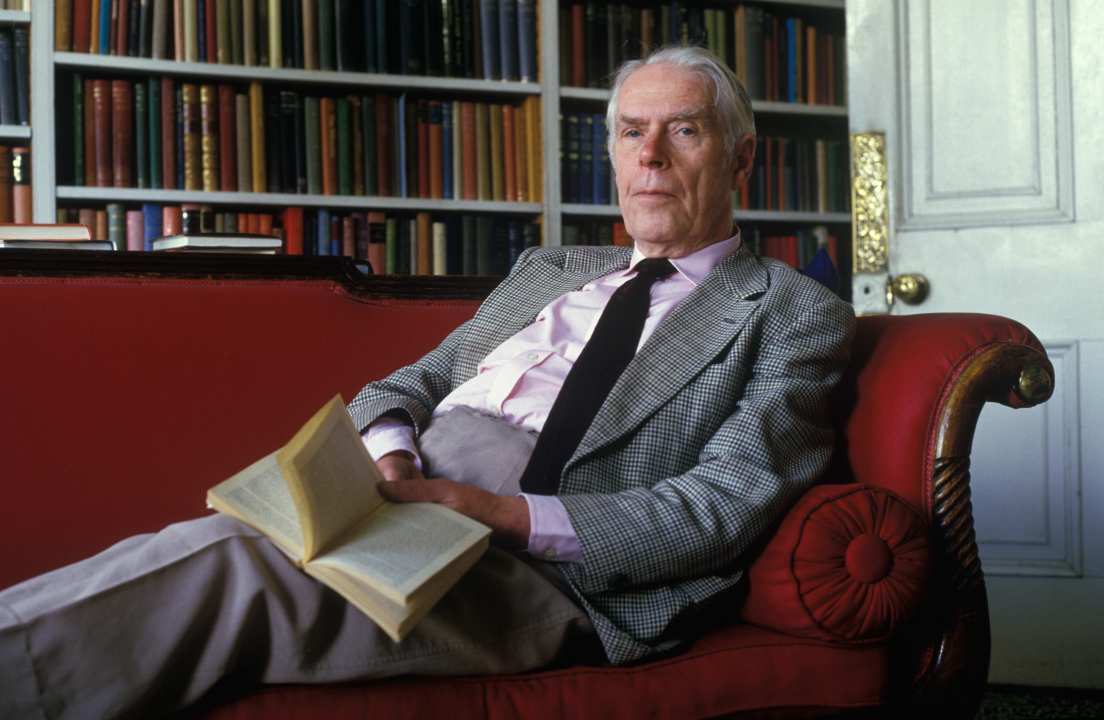

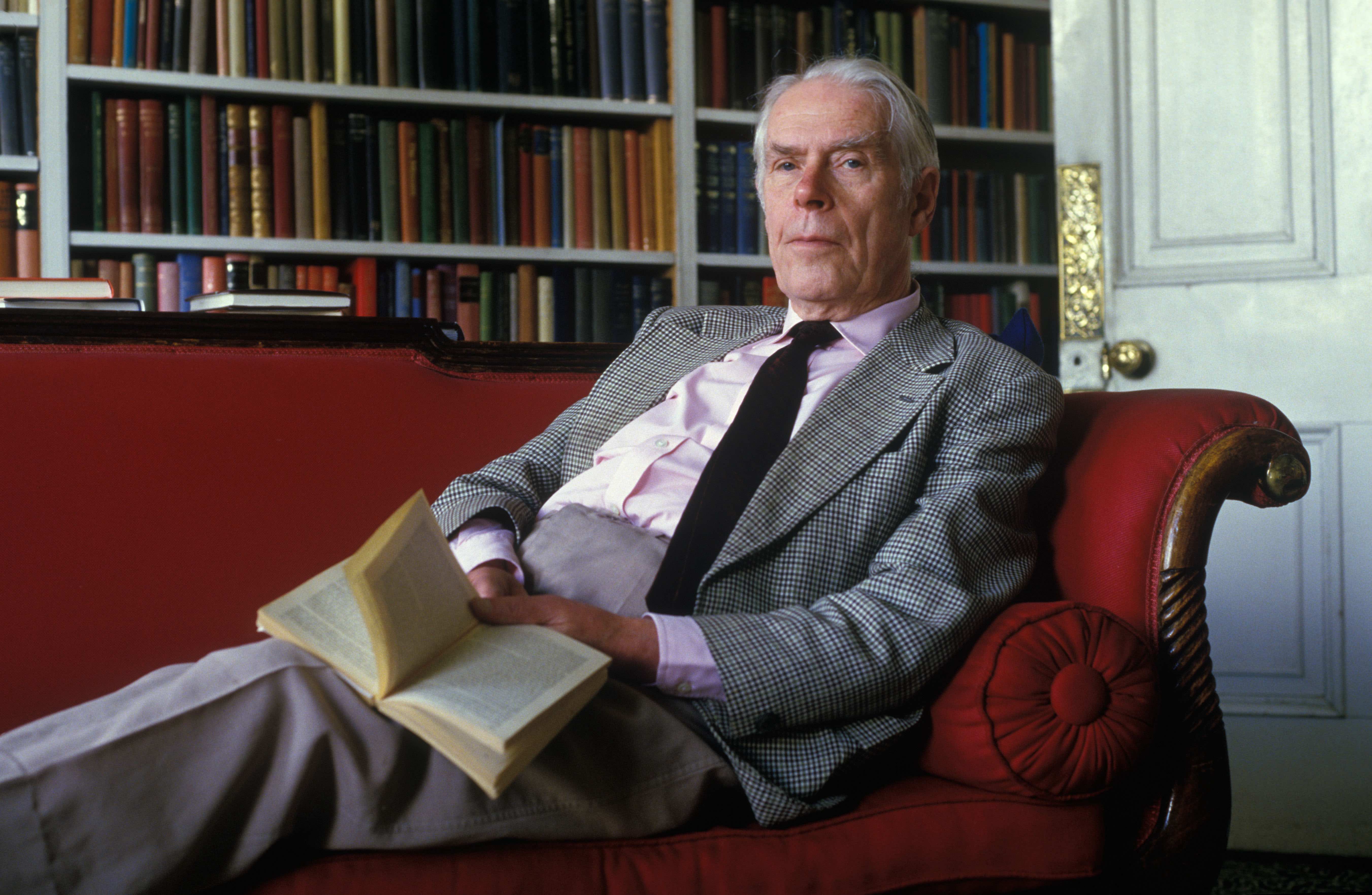

Fifty years ago today, a literary masterwork of the 20th century reached its conclusion with the publication of Hearing Secret Harmonies, the final volume in Anthony Powell’s 12-novel sequence A Dance to the Music of Time.

Inspired by the painting of the same name by the 17th-century French artist Nicolas Poussin (which you, like Powell, can see at the Wallace Collection), the series began with A Question of Upbringing, published a quarter of a century earlier in 1951. This introduced us to the English narrator of the whole endeavour, Nicholas Jenkins (uncoincidentally he shares the Christian name of the painter, albeit with an Anglicised aitch), who attends a boarding school – unnamed but modelled on Powell’s time at Eton. It begins with a memorable image of a lad in a cap ‘at least a size too small’ running – or rather ‘hobbling unevenly’ – through the dusk. It’s December 1921 and the reader is at the start of a journey that encompasses nigh-on a million words and the next 50 years.

As you turn the pages you are introduced to a changing cast of characters who move in and out of the authorial frame as Jenkins gives us a ring-side seat to witness their humanity, failings, vanities, marriages, careers and triumphs. Characters come and go… and before you know it they are back again, reimagined, transformed or simply still grubbing along as before – just older, greyer and usually no wiser. Much like in life.

The thing about Dance (as Powell himself referred to it in his memoirs) is that you don’t remember the plots – or at least I don’t. What stays with you is a handful of the characters, whether that’s Uncle Giles or Books Bagshaw, X. Trapnell or the ghastly Kenneth Widmerpool (of whom I can think of at least two or three real-life versions). And what you remember most of all is simply being there – occupying the world concocted by Powell over 25 gloriously fecund years. It’s a mellifluous merry-go-round of life as you pass through the middle 50 years of the 20th century. Dance is a testament to an era, one long gone and scarcely understood today but one that is therefore increasingly valuable.

In her important 2017 biography of Powell, Hilary Spurling notes that when Kingsley Amis finished reading the last book in the series he said it felt ‘like the sadness that descends when the last chord of a great symphony fades into silence’. Spurling also quotes Michael Frayn: ‘The world remembered by Nicholas Jenkins is in many ways better established, more publicly accessible, more objectively there, than the worlds we ourselves remember.’

Try it today and it’s likely that the Dance literary project wouldn’t fly. It would surely be castigated as not so much a Dance to the Music of Time but a jaunt through the corridors of privilege. (The irony is that those who would cancel it most vociferously would probably have no problem with Gatsby, say, even though that is a testament to US privilege – and conspicuously more so than the sober, rather bourgeois outlook of Nick Jenkins.) Fortunately, ‘privilege’ was not a consideration for the publisher nor the sequence’s avid readers in the 1950s through to the 1970s. And even now, for all that it details the lives of an Old Etonian at school and then his and his circle’s exploits as they embrace London society and adulthood in the 1920s and 1930s, before the upset of war then the onset of middle age in 1940s, 1950s and 1960s – the books’ appeal is far reaching.

‘The world remembered by Nicholas Jenkins is in many ways better established, more publicly accessible, more objectively there, than the worlds we ourselves remember’

The series is still in print, and you can find some eminent Dance fans in unexpected places. When I interviewed Ian Rankin for Spear’s a week before the pandemic struck in March 2020, he told me he hoped his Rebus detective series – itself stretching across more than 30 years – could be a sort of Dance to the Music of Time, set against Edinburgh and covering the late 20th and early 21st century – albeit with a rather difference milieu of characters. In 2006, when he was Sue Lawley’s guest on Desert Island Discs, he had chosen Powell’s work to have with him in his sandy isolation. He wasn’t the first: Jilly Cooper, she of Rivals and Riders fame, also had it as her choice when she was interviewed by Roy Plomley in 1975 – and John Peel picked it in 1990. On the face of it it’s hard to see Peel and Powell in the same sentence but, then, that’s the transcendent appeal of the book. (Interestingly, Powell’s own choice on Desert Island Discs in 1976 was Mikhail Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time and his luxury was a bottle of red wine a day.)

Its vast cast of characters – the cranks, dons, struggling painters, impecunious uncles, composers, men on the make, politicians and denizens of Grub Street like X. Trapnell – and their endless interactions and deliciously observed foibles speak to us. In its way Dance is a literary soap-opera, albeit on an unparalleled scale. And where Powell’s genius lies most is in his fluidic and seamless ability to blend the past – through memory and exposition – with the present action of each book, so that before you know it you’ve travelled through a span of time and space, crossing perhaps decades or generations before you arrive where you started or maybe somewhere else altogether, into a new episode. Spurling says that Powell, who died in 2000 aged 94, was in a ‘hypnotic dreamlike state’ when he wrote it. In his own words he said that he was ‘conscious of an external force taking over the job, something beyond the process of thought, conscious planning, or invention’.

I can still remember the doomy feeling of heartbreak that accompanied reaching the final page of Hearing Secret Harmonies. How better, then, than to mark this important literary anniversary than by reading or re-reading this enormous sequence of books? And, perhaps, if you haven’t already, it’s time to treat a son or daughter or niece or nephew or grandchild to a copy of their own? After all, we want to make sure that the dance goes on.

Comments