Like the most desperate of priests, and the most marginal of activists, Nick Cohen wants us all to be like him. He’s an angry journalist who can’t imagine why everyone doesn’t think like an angry journalist.

In What lonely planet are they on? Cohen attempts a take-down of travel guide publisher Lonely Planet, implying that they’re all liberal lefties, happy to whitewash the crimes of dictators in order to sell more books. To do so he cites the work of Thomas Kohnstamm, a Lonely Planet author who admits making stuff up (though, here and elsewhere, Kohnstamm maintains that the job he was commissioned for was a desk-edit, rather than a research trip). The idea appears not to have occurred to Cohen that a man who is happy to invent material for a guidebook might also be happy to invent material for his own memoir. Some people want to believe Kohnstamm’s story about sex in a Brazilian café, while disbelieving his recommendations for good bars in Bogota. I choose the reverse. Boring, I know.

Cohen bobbles on for a while about the Soviet communists – helpfully reminding us, guidebook-style, that they “killed more than the Nazis” – before snorting at Lonely Planet’s cautiously optimistic take on pre-revolutionary Syria. Perhaps Cohen doesn’t know much about the Middle East, but there really were, on all sides, high hopes for Syria in the few years after Bashar al-Assad’s rise to power: indeed, the Western media dubbed the period the “Damascus Spring”. I can personally vouch for the accuracy of Lonely Planet’s identification of “a feeling of optimism in the capital” around that time. It’s easy to imply, as Cohen does, that writing about gallery openings and new hotels is a pernicious insult when placed beside the murderous violence we are now witnessing, but then hindsight has always been a seductive tool. At the time, in 2006, Syria-watchers were well aware that the opening of the Four Seasons in Damascus signalled the possibility of improving economic liberalisation. By 2009 even The Economist – notorious, of course, for its lefty whitewashing – was noting that “reforms have tapped suppressed entrepreneurial vigour [in Syria]”. Then the wheels came off, with unspeakably awful consequences. Journalists were wrong about Syria. Academics were wrong. Diplomats were wrong. Syrians themselves were wrong. But Cohen thinks the author of the Lonely Planet should have got it right.

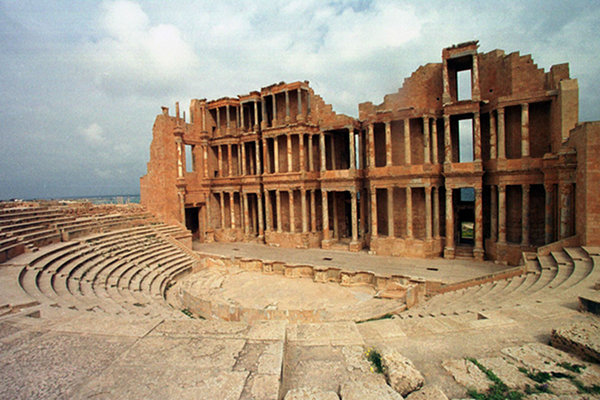

And so Cohen continues, fingering the “excuses Lonely Planet made for the Libyan ancien régime”, as if they weren’t simply what everybody was saying at the time. A detailed critique of Gaddafi’s social policy would have been as out of place in a Libya guide as a discussion of gun crime in a London guide, or an evaluation of Obamacare in a guide to Florida. You look elsewhere for such material.

It seems obvious, but – short of parliamentary junkets, perhaps – people don’t go to “difficult” destinations to laud the government. They go to see the sights, sample the culture and spend time with the locals. Misidentification of a populace with its government is a peculiarly Western trait; people who actually live under unrepresentative governments – like Syrians, say, or Iranians – rarely do it. Cohen rightly notes that guidebooks to these places often pay lip-service to the antics of politicians. He fails to realise, though, that to do anything else would likely result in a ban, leading to fewer tourist arrivals.

Hurrah, you say. But I’m old-fashioned enough to think that independent tourism, of the kind guidebooks encourage, can pass under the radar of governments to benefit people – tourists and locals – directly. Eliminate it, whether for the sake of principle or merely through sloppy editing, and you’re left with organised mass tourism. That tends to keep money out of local communities, benefiting big business and, in places where corruption exists, governments. By facilitating independent travel, guidebooks are a force for social and economic good. If they neglect to identify every case of state-sponsored torture in order to remain legal in the destination they cover, that’s bad – but not as bad as leaving the people of that country isolated and alone.

It all comes down to critical reading. Cohen seems to be saying that he’s clever enough to read between the lines but the poor misguided folk who buy Lonely Planet in their millions simply aren’t. Guidebooks exist to help people find a room, have a meal and get a drink, with the added bonus of directions to a quiet beach or a pretty village. A paragraph or two of political background can be diverting, but you’d hardly base a world-view on what you read in your guidebook, would you? Nick Cohen, angry journalist, is savaging a paper tiger.

Sounds like he needs a holiday.

Matthew Teller writes about the Middle East for newspapers and magazines around the world. He has been an author for Rough Guides since 1996. He blogs at QuiteAlone.com and tweets @matthewteller.

Comments