As we all know, only the best friends can deliver bad personal news. And so it was for me about six months ago, over a seafood lunch, that one of my closest pals gave me the ghastly tidings. My friend had just stayed in my small but fabulously located London flat for a fortnight, while I was travelling. He was suitably grateful, but less than effusive about the living conditions. After some humming and hahing, he got to the point. ‘Mate, your flat is a dump. Great location and all that, but eesh, when did you last do it up?!’

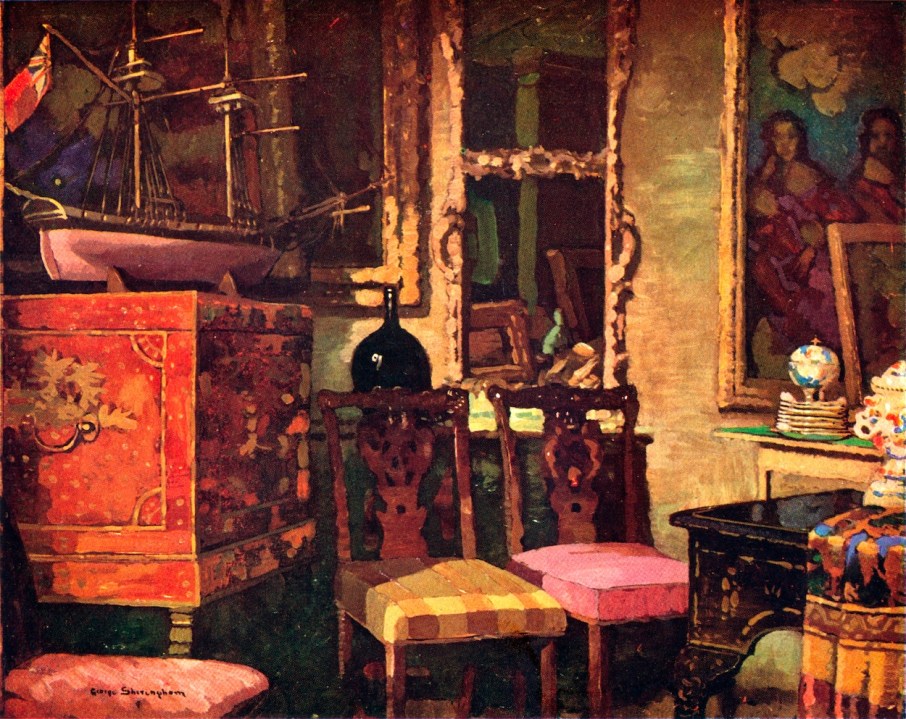

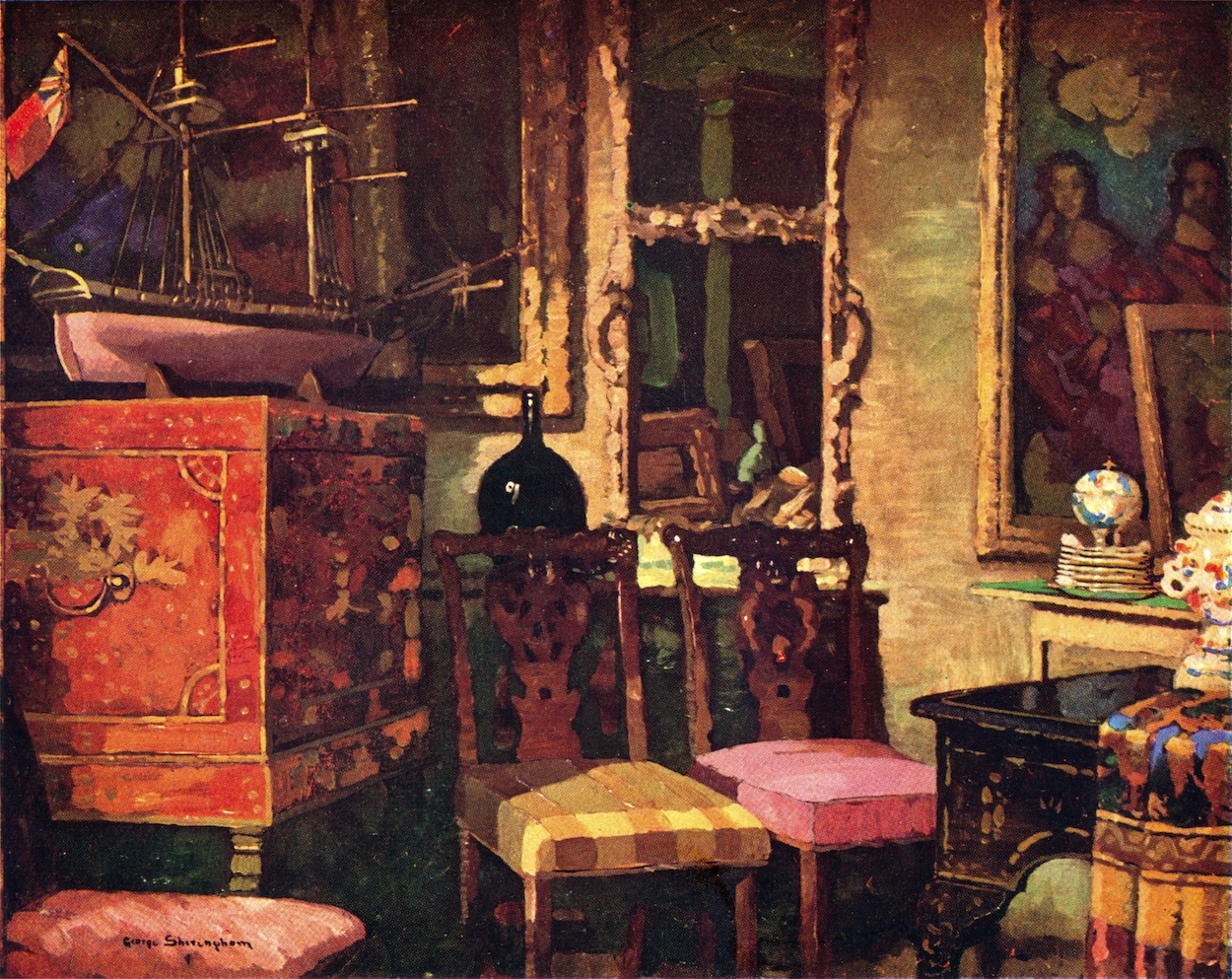

O for the gift to see our homes as others see them. Armed with this gift I went back to my beloved domicile, and realised, my God, he’s right. What I thought was a noble state of benign neglect – who cares if there’s a mustard stain on the ceiling (thank you, my dyspraxic ex-wife) – was actually my place turning into ‘a dump’. And as for the Ikea furniture, instead of stating ‘a wise man unconcerned by trivial aesthetics lives here’ it abruptly screamed: ‘Why are you still living like a student?’ And so began the Great Summer Makeover of my accommodation, during which I have discovered that, right now, Lovely Old Things are astonishingly cheap.

Other Spectator writers have dwelt eloquently with historic furniture. Nonetheless, my own experience might add something. The first item I bought, in a London antique shop, was an exquisite Italian chest of drawers, all polished olivewood and delicate parquetry (a new word to me). It dates from the 18th century. Before I began my new venture, I might have wildly guessed it would cost a thousand quid. It cost a few hundred.

The unexpected cheapness got far more startling than that. Online I bought an Anglo-Indian ‘Hoshiarpur’ cake stand, of rosewood and bone, dating from about 1900. It’s wobbly, characterful, deliciously pretty and it sings of the British Raj, of matrons leaning across a Simla drawing room for another slice of Madeira cake. It also makes a brilliant place to drop keys, wallets, AirPods. £80.

Online I sourced a 19th-century hardwood cabinet with gorgeous metallic inlay, apparently from the Balkans. Also perfectly sized for the intended space. That set me back £50. Yes, £50. It actually cost me more to have it driven down to London from Lancashire. But that itself made it more tantalising: how did a 150-year-old Carpathian chest end up near Salford? This is another thing I have learned to love about old things: the stories.

By June I was in an antique-hunting frenzy and I went as far as driving to Suffolk to browse a massive warehouse. Among other items, I ended up with an arts and crafts ‘whatnot’ (another new word) for £90 and a William IV mahogany writing table, which looks like it’s worth £2,000, and cost £120. Ridiculous.

During my Suffolk jaunt, I got chatting with the warehouse owner. He explained the reasons which have made these objects such good value. Basically: lots of old people are dying (flooding the market with brown furniture). Houses are getting smaller, we don’t have room for massive chunks of wood. Pianos are so unwanted ‘we have to bury them in fields’. Also, old furniture – pre-second world war, say – is out of fashion, everyone wants ‘shabby chic’, ‘mid-century Danish’, or anything that looks ‘industrial’ – that ubiquitous, bare-brick aesthetic. Thus it is that a sad rusting metal pharmacy cabinet from 1952 might cost you more than a delicious late Georgian elmwood console table.

My astonishment at all this was only accentuated when I asked an actual expert – Dorian Bowen, one of Britain’s best interior designers – what I was seeing. He confirmed that the phenomenon is very real, and rather sad. ‘This is meant to be the age of sustainability, but all we want is the new. You can find incredible bargains. And take a longer look – it’s not just side tables and dressers, it’s not just brown furniture.’

Pianos are so unwanted ‘we have to bury them in fields’

Not just furniture? That cued me up for a second session of exploration and purchase. And so I learned that almost anything old and decorative is stupidly cheap. Vintage porcelain and crockery, for instance – Wedgwood, Spode, all that – is often basically worthless. So much so, this Telegraph writer was reduced to offering her family dinner service for a charity smashfest.

My own particular revelation was historic glassware. Handblown, with quirks and flaws that make it, to me, finer than anything lathed by a machine. I found that you can buy Georgian toasting glasses, 1780s rummers, fragile but handsome vessels that might have touched the lips of Nelson and Byron – for the same price as a nice generic modern wine glass from John Lewis.

Indeed, historic handblown glass is actually cheaper than modern handblown glass. My favourite purchase was a Georgian ‘amethyst’ wine glass, which is so pretty it looks like a jewel of a goblet in a blissful dream. £42 on eBay. Why is the smaller stuff getting cheaper, like the furniture? Again, there is a confluence of factors. A big one is the existence of sites like eBay and Etsy, where ordinary people can sell their possessions, person to person, without the faff and mark-ups of dealers, auctioneers, specialist shops. This lowers prices overall, as availability explodes.

I wonder too if there are more profound reasons. Perhaps we have simply reached a stage where humanity has created so much stuff we are saturated. Perhaps ageing, dwindling populations mean the loveliness that is already out there is generously shared between fewer people. And perhaps it is because we are getting stupider, and our tastes are, therefore, becoming blander and coarser (I have noted, incidentally, that ‘antiques’ connected to the Nazis are a peculiar exception to this budget trend).

Of course, like anyone doing this trade, I have sometimes wondered if I am buying bargains that will in future make a profit. I’ve also discovered that I really don’t care. Maybe these old things will never come back into fashion, but what does it matter if you can sip Malbec from a precious 260-year-old dwarf ale glass, standing next to your inlaid walnut 1840s etagere, and feel like a slender aristocrat in a marvellous film, and it all costs the same as a sushi dinner from Deliveroo.

Comments