When the Covid pandemic began, one fear was that the virus would tear through prisons and cause up to 5,000 deaths. The prison service, at its best in a crisis, introduced lockdowns and control measures. These were effective and, from March 2020 to September last year, only 207 prisoners died having tested positive for Covid-19 within the previous 60 days or with the virus confirmed as a contributory factor post-mortem.

Locking down was always going to be the easy bit – there is an old prison-officer saying that ‘happiness is door-shaped’ (meaning that prisoners who are locked up can’t do any harm). The hard bit is getting prisoners back into work, education or training. And the lingering effect of lockdown policies still makes it hard today.

Prisoners are not being motivated to get off the wing and into activities. They’ve become bored and indolent

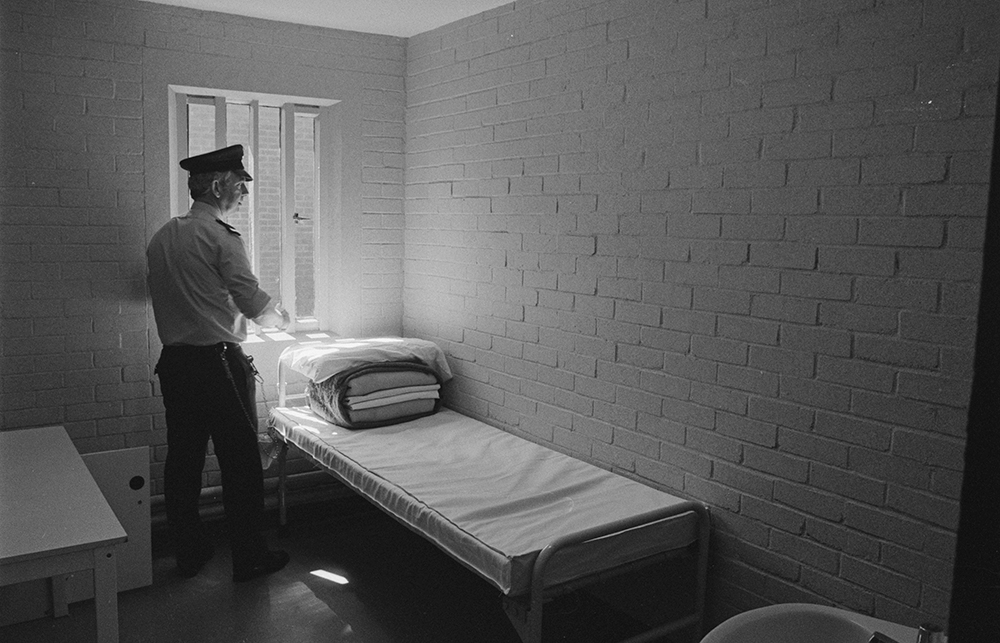

Since May last year, when the final Covid restrictions were lifted, we’ve inspected 20 training prisons – jails that are supposed to be giving lower-risk prisoners the skills they need to resettle successfully after finishing their sentences. It has been a depressing experience – wings are quiet, not because prisoners are in workshops or classrooms, but because they are stuck behind their doors. Sometimes that can mean two men squeezed into a 12ft by 6ft cell, with an unscreened lavatory, a sink and a plastic chair, for up to 22 hours a day. They are learning nothing except how to survive in prison. They pass the time sleeping or watching television.

We have inspected prisons with excellent facilities, such as Onley in Warwickshire, Ranby in Nottinghamshire and Wayland in Norfolk. Yet we found empty workshops and classrooms, greenhouses collapsing and market gardens overgrown. Prisoners, many of whom have never worked in their lives, are not being motivated to get off the wing and into activities. They have become bored and indolent.

Some of this reluctance to open up may be a reaction to the explosion in prison violence between 2015 and 2019. That was fuelled by large quantities of synthetic psychoactive drugs such as spice that were getting in, often soaked into letters, books or clothes. Around the same time, to save money, the prison service reduced staffing and, catastrophically, allowed a large cohort of experienced staff to take early retirement.

Different batches of drugs had different effects. Some sent prisoners to sleep. Others made them manic or aggressive. The effect of spice on the mentally ill was often disastrous. We saw sharp increases in self-harm and, in some jails, daily ambulance call-outs.

Recently, the introduction of body, mail and bag scanners and the use of sniffer dogs means the drug supply and related violence have fallen. The arrival of this technology coincided with the pandemic and led to a belief that the way to make prisons safe was to keep prisoners locked down in their cells.

The evidence for this is weak. In the first decade of the century, prisoners spent much more time out of their cells and levels of violence were far lower. More importantly, the aim of prisons should not just be to keep inmates and staff safe. Prisons also have a responsibility to make prisoners less likely to reoffend when they come out and therefore keep the public safe. That will not happen if prisoners spend months and years stuck behind their doors.

The public is not getting value for money; it costs an average of £45,000 to keep someone in prison for a year. If we want ex-prisoners to take their place back in society, look after their children, get work, pay their taxes and stop causing trouble in their communities then we need to make sure that prison gives them the support they need.

One of the most basic skills in gaining employment is, of course, being able to read. You might imagine that prison would be the perfect opportunity for the 50 per cent of prisoners who are functionally illiterate to be taught this skill. Astonishingly, however, those with the most need tend to receive the least help. The Shannon Trust charity aims to train prisoner mentors to teach their peers to read, but the success of this work is entirely dependent on prisoners being unlocked and having the privacy and space to run sessions.

Where prisoners are only out of their cells for a couple of hours a day, they end up having to choose between learning to read, taking a shower or getting some fresh air. I came across one prisoner who had come into prison unable to read and who was about to leave four years later, still unable to read.

It is difficult to pin down the exact cause of such inertia. Certainly, in parts of the south-east, there are serious staff shortages, and some prisons seem to struggle to hang on to the staff that they have. But we see a lack of purposeful activity even in parts of the country where there are plenty of officers. Governors are also quick to blame the inexperience of staff who have never seen a prison operating normally, but, nine months after restrictions were lifted, this excuse is starting to sound very thin. Some prison leaders appear to lack the ambition to focus on education and rehabilitation, preferring to keep things locked down and avoid confrontation with the trade unions.

There are some welcome exceptions. Coldingley, a Category C prison in Surrey, had a Covid outbreak when we inspected it in January last year and yet we still found prisoners out of their cells for far longer periods than we have seen elsewhere. This was also true at Parc young offender institution (YOI) in south Wales. Both prisons have experienced and dynamic governors.

Yet last week I was in a YOI where attendance in education was at 50 per cent. If that had been a school, it would have been closed down. In one jail, after walking along a corridor of empty classrooms, I found three education managers sitting drinking tea in their office. I asked them why there were no classes that day and they told me they were short-staffed. When I asked them why they could not cover the lessons themselves – as any decent school leader would – they looked at me in disbelief. There are no irate parents to complain if lessons are cancelled, just prisoners, and no one minds if they do not get taught. Until they come out…

Comments